Brief

Research

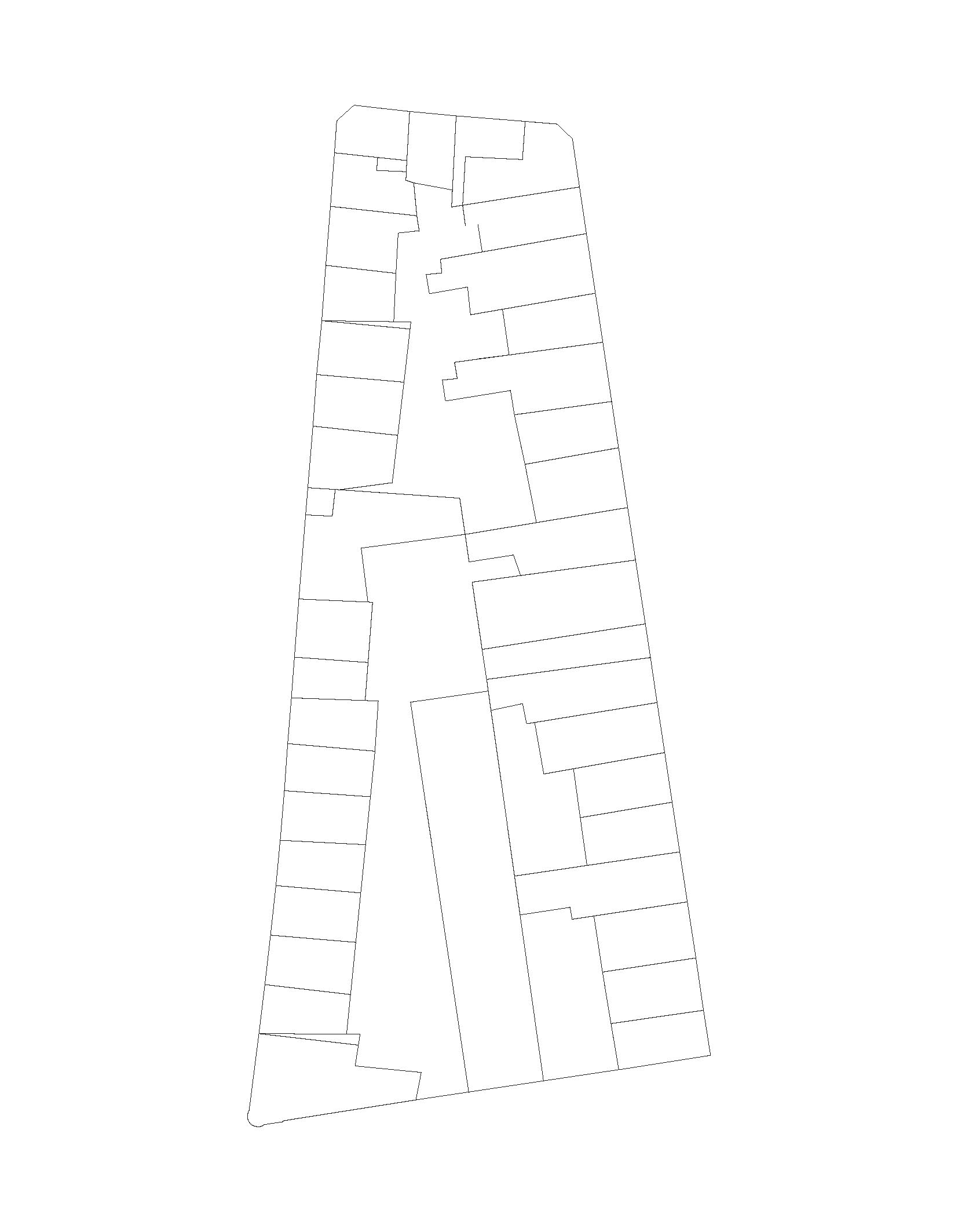

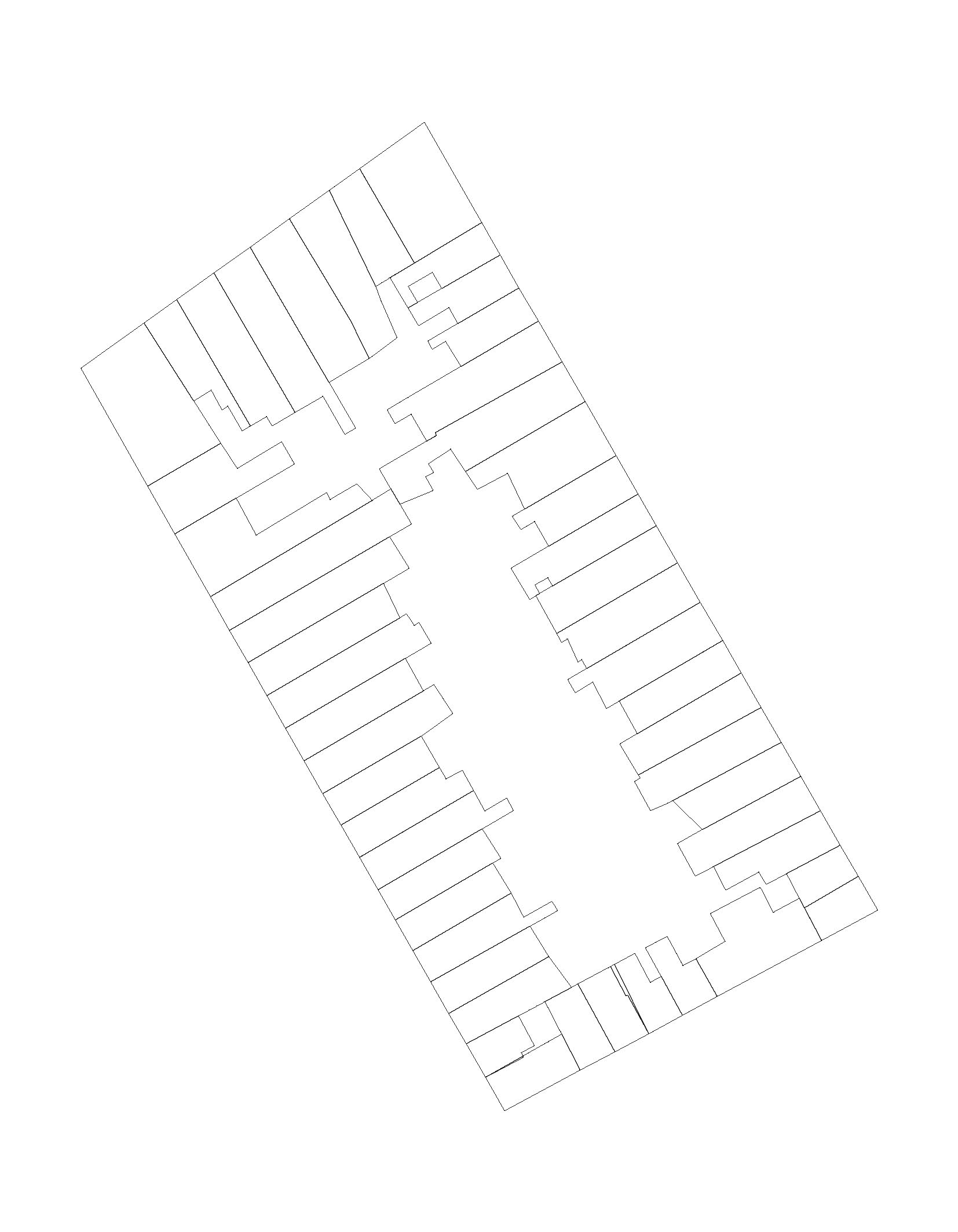

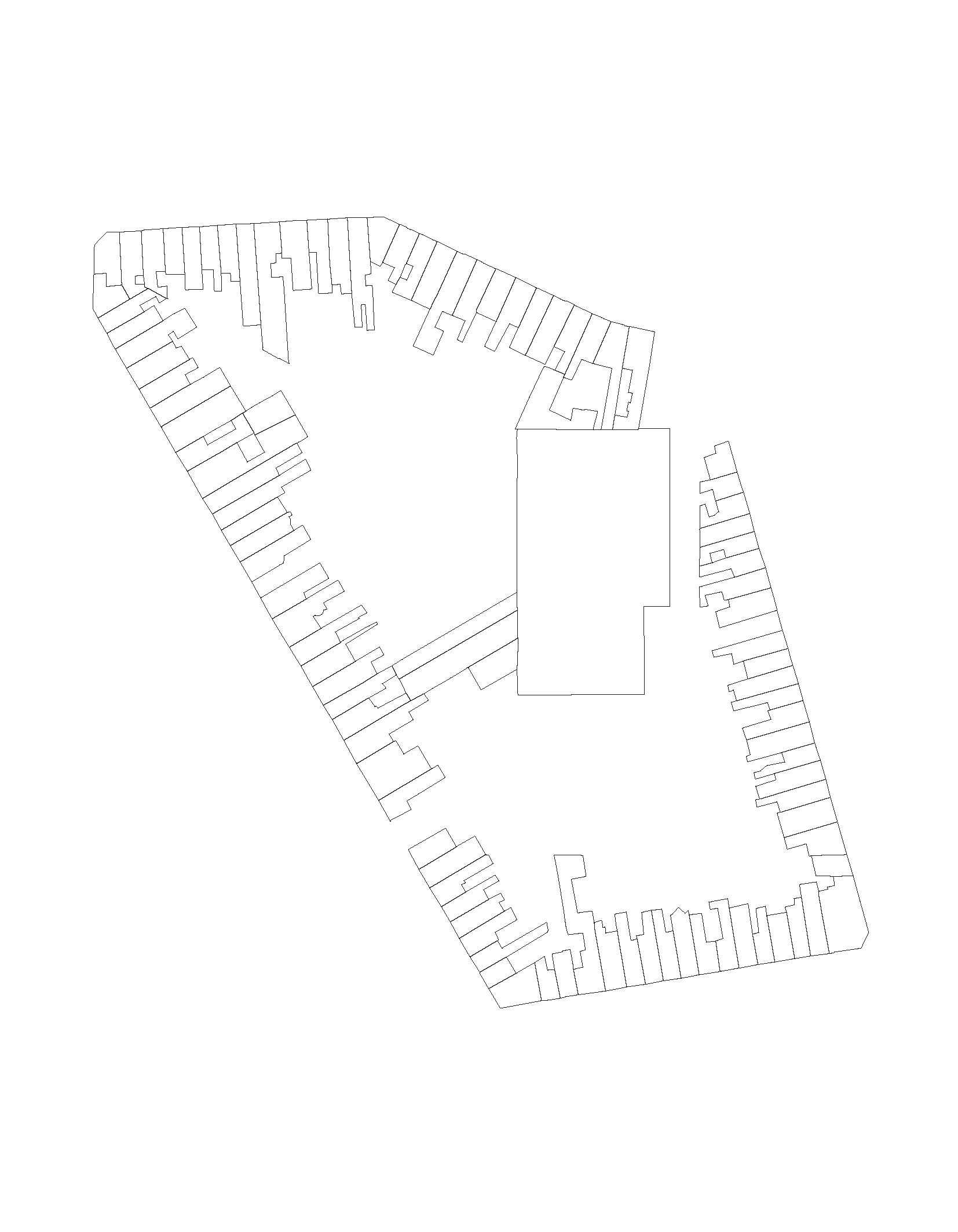

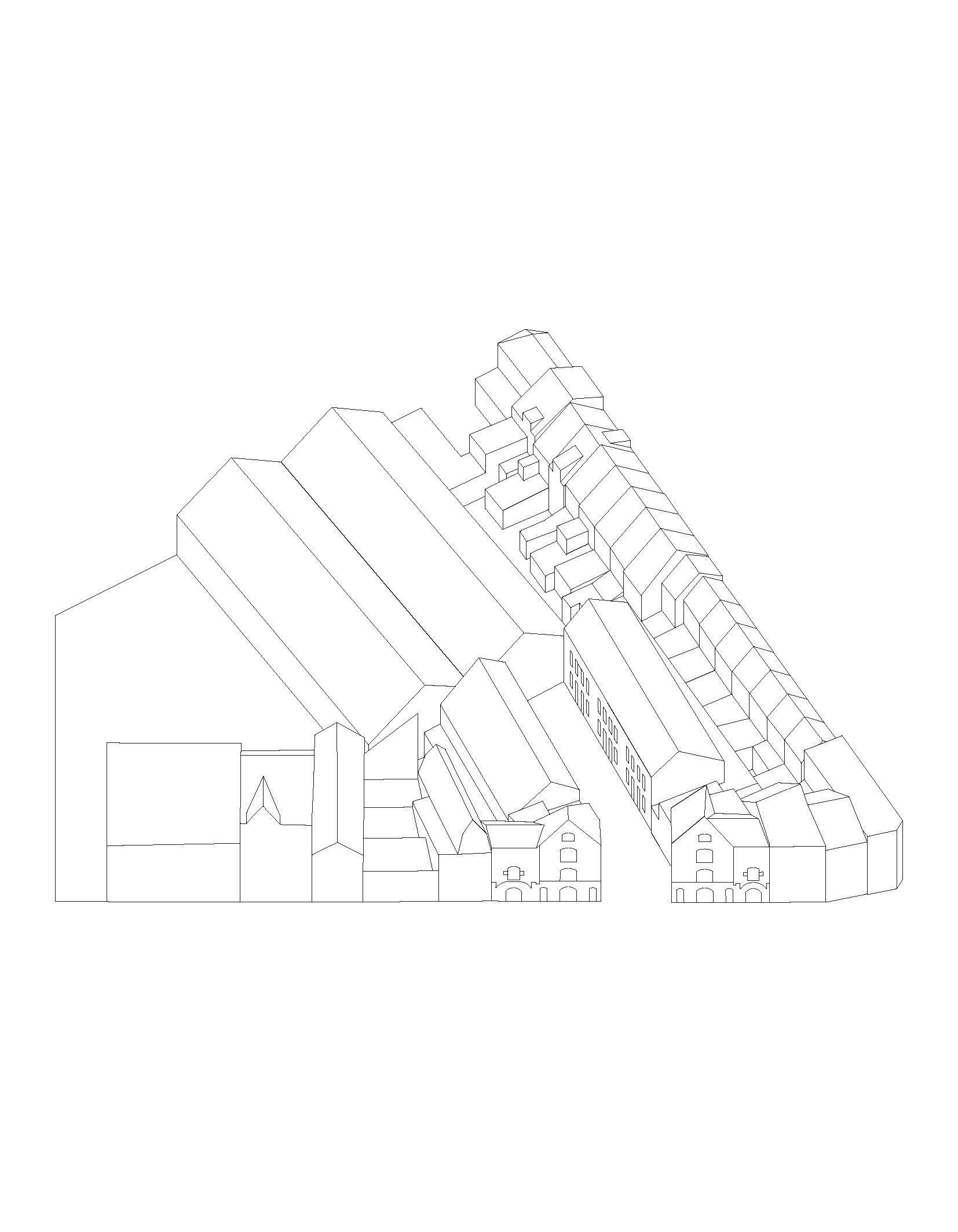

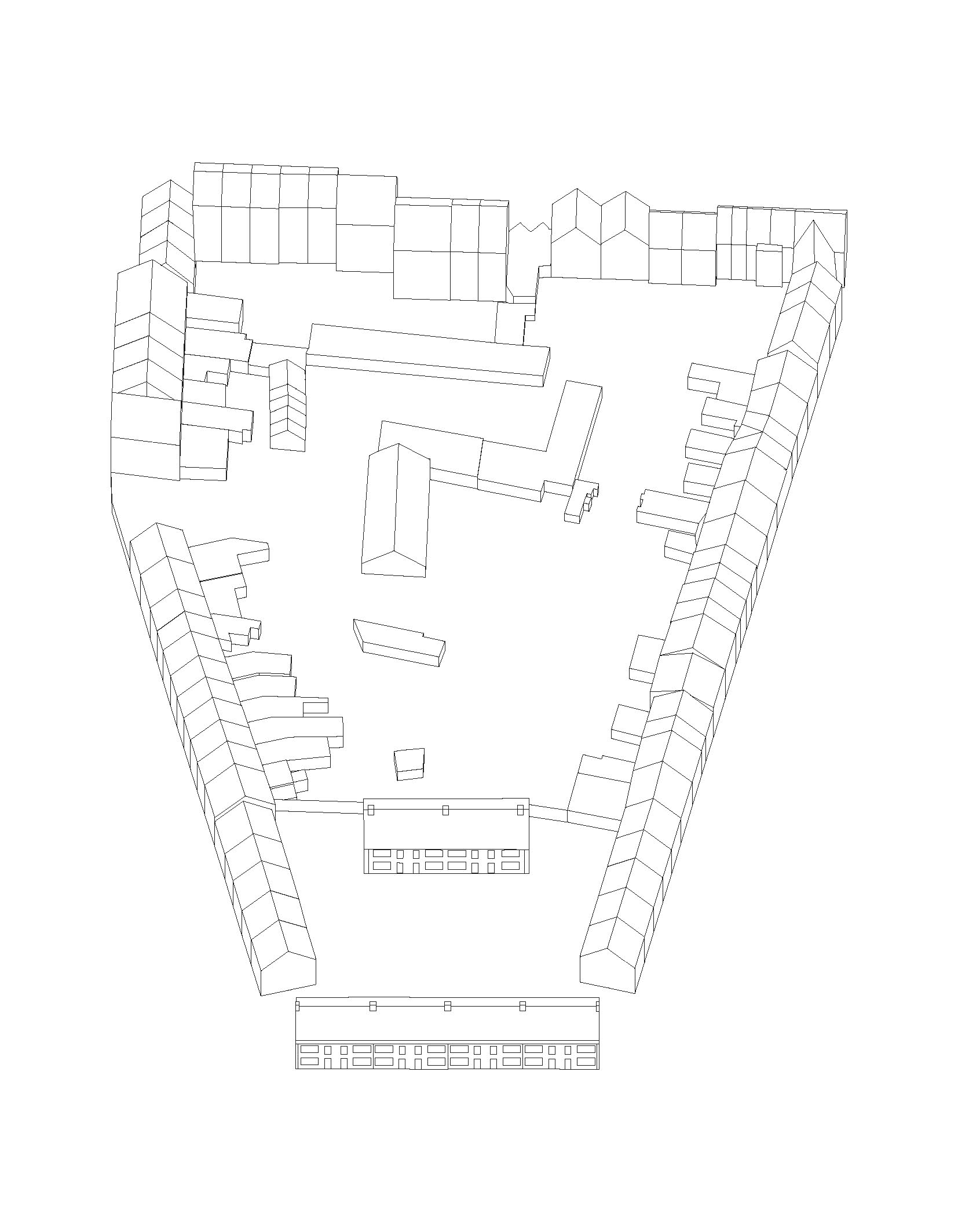

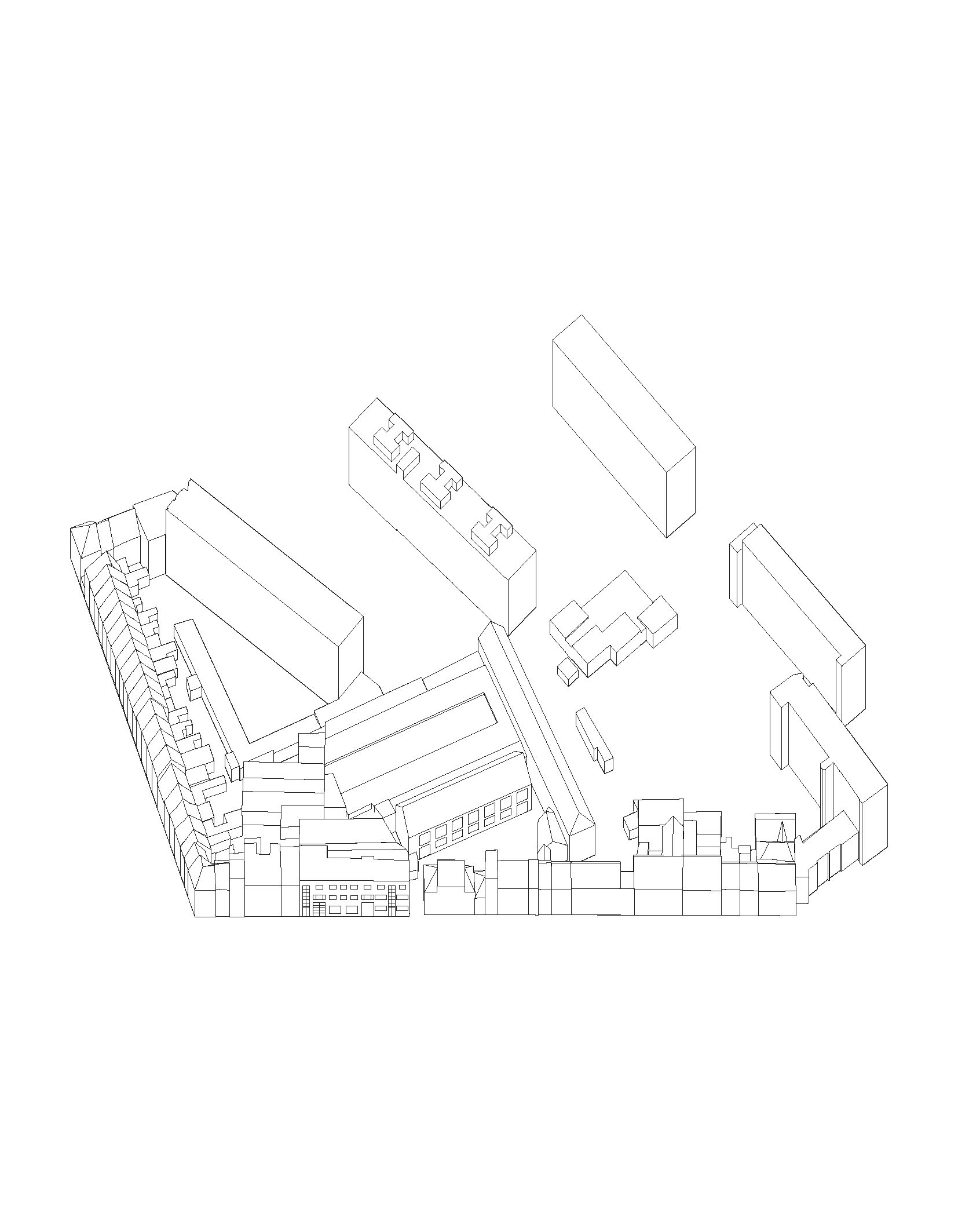

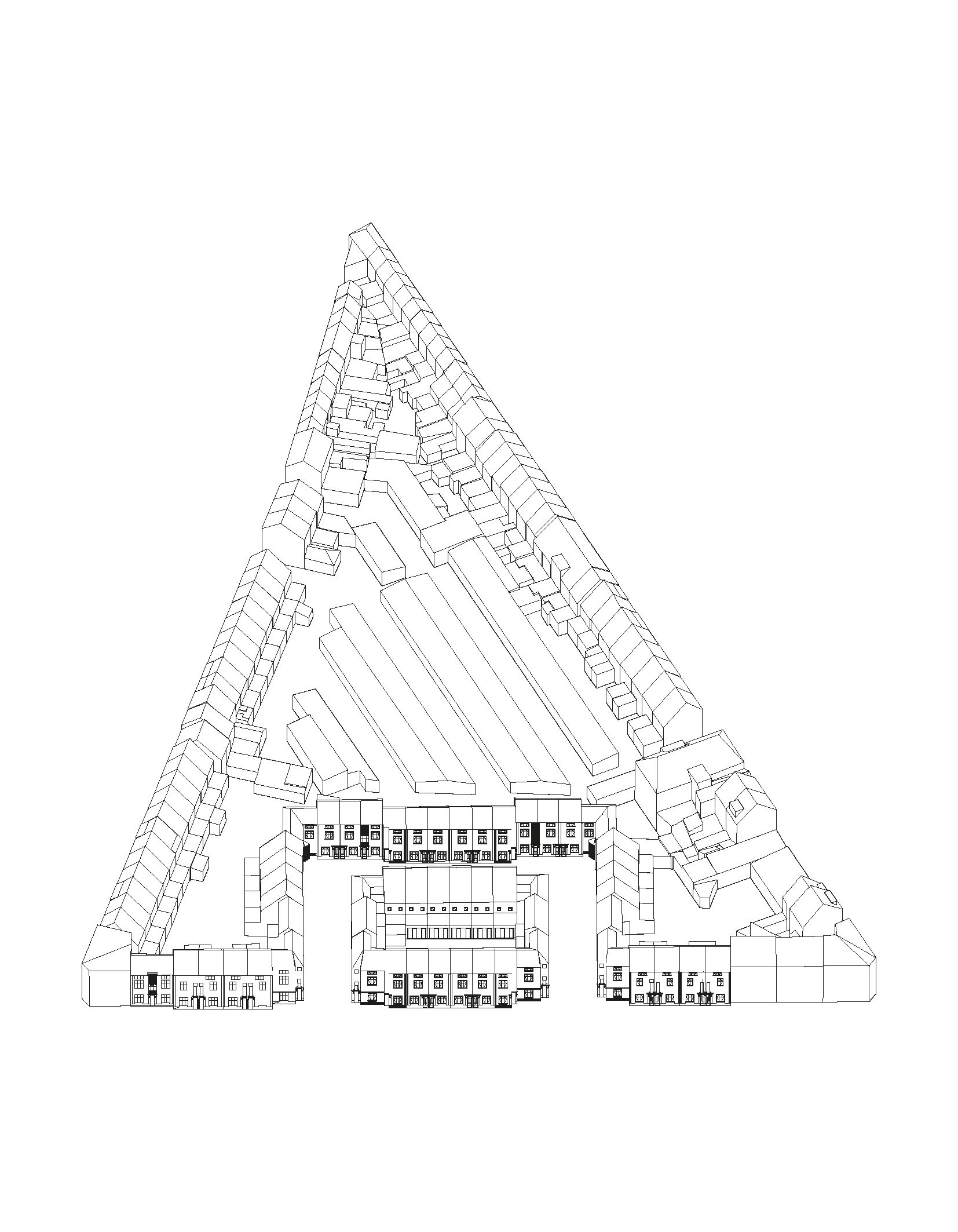

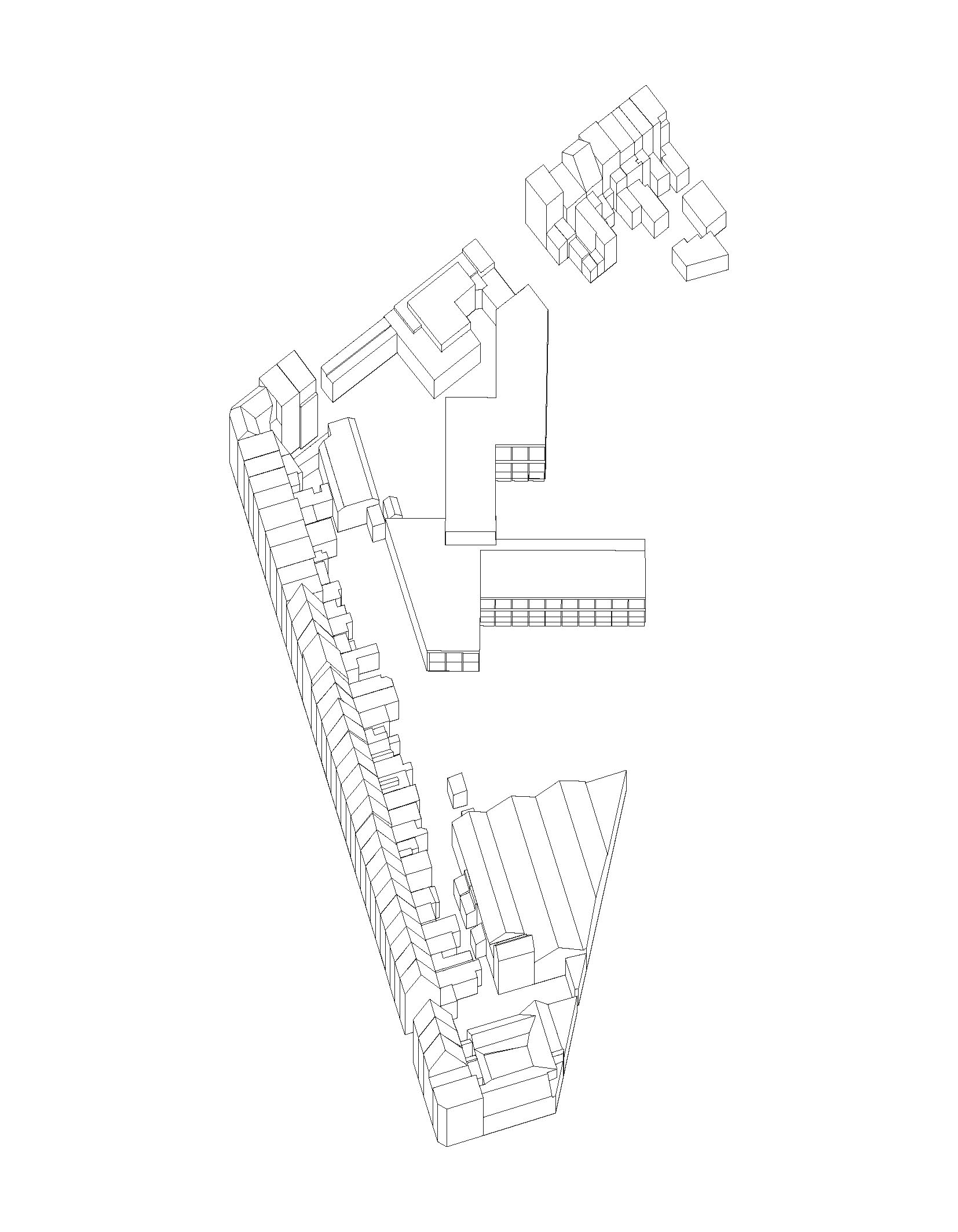

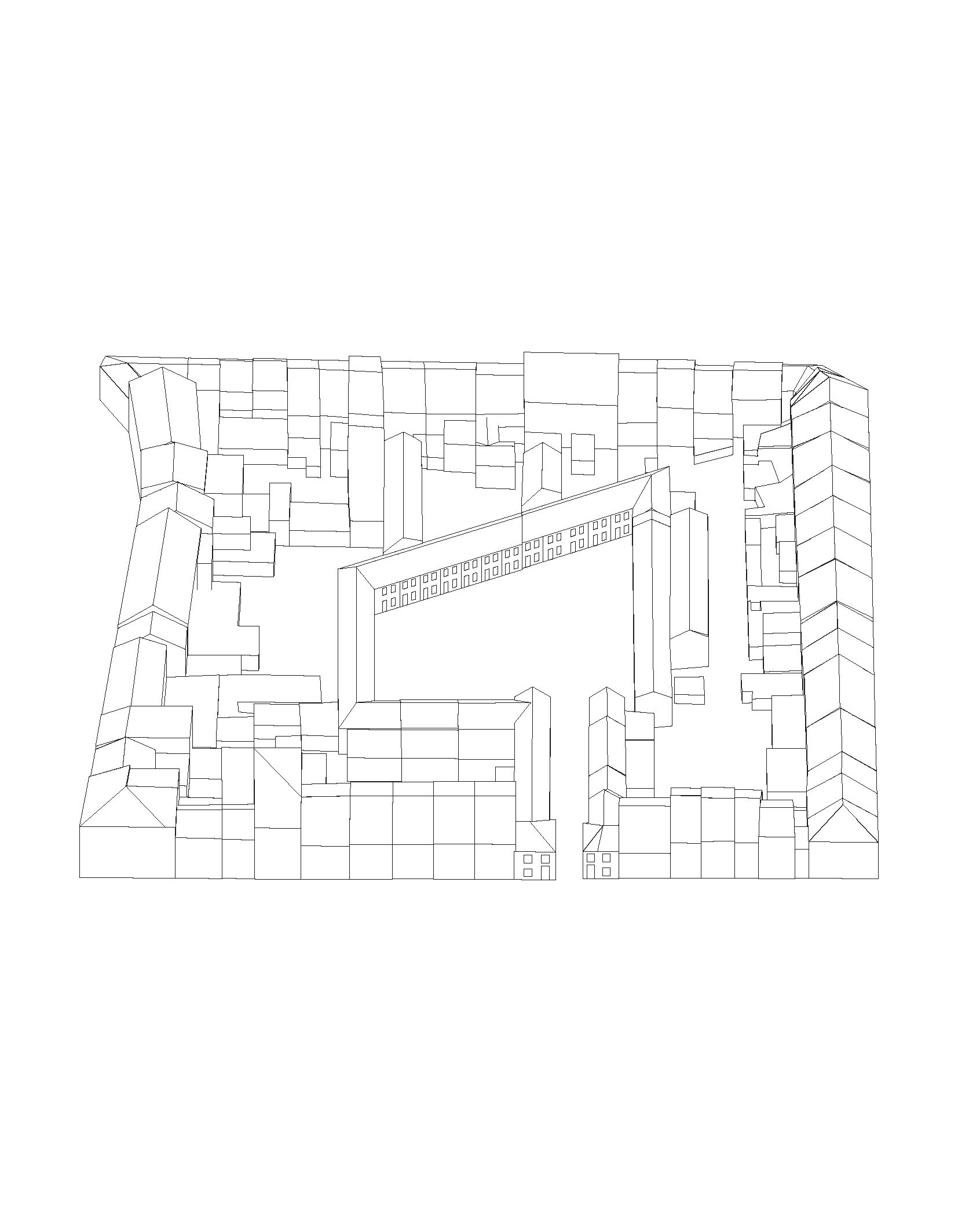

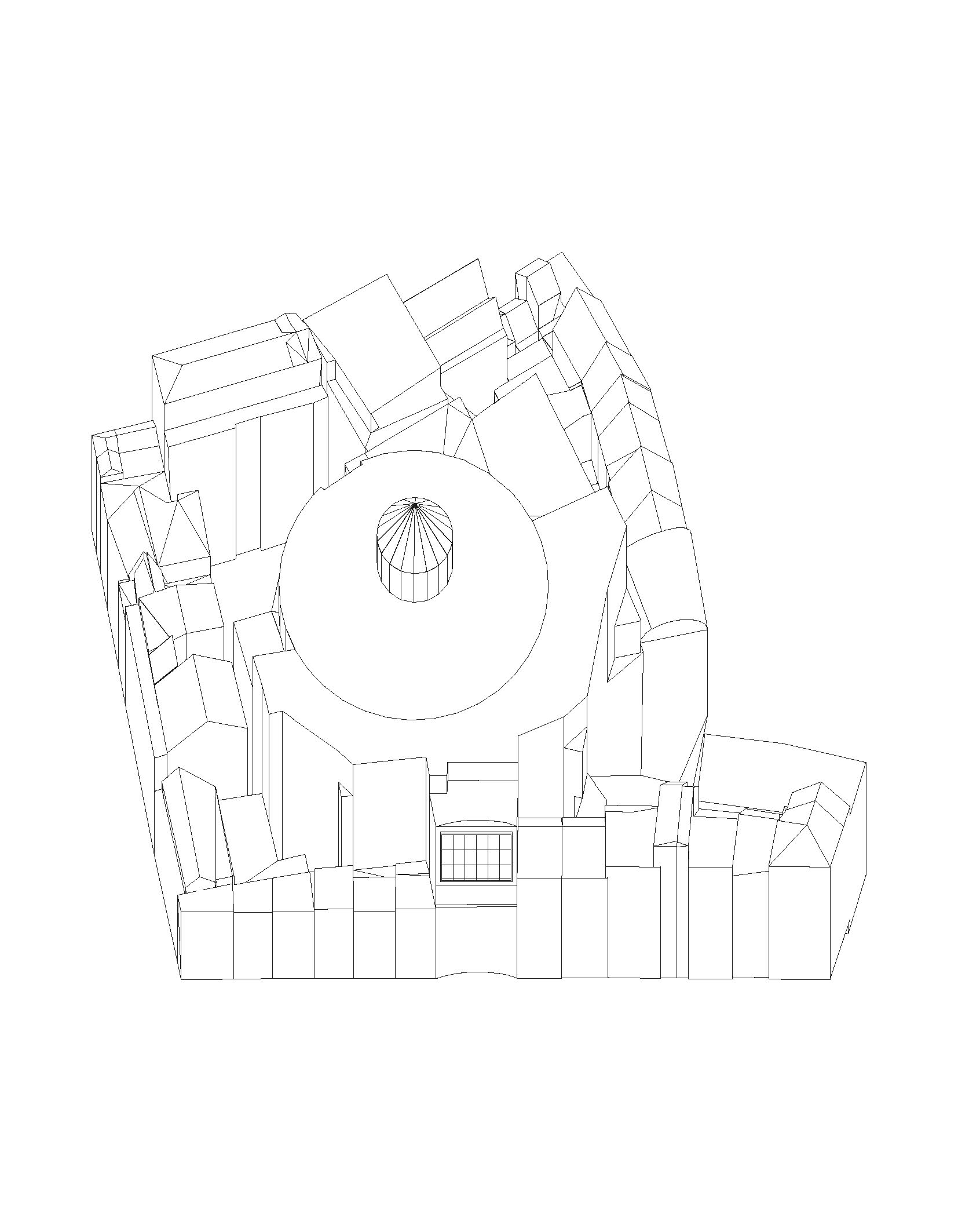

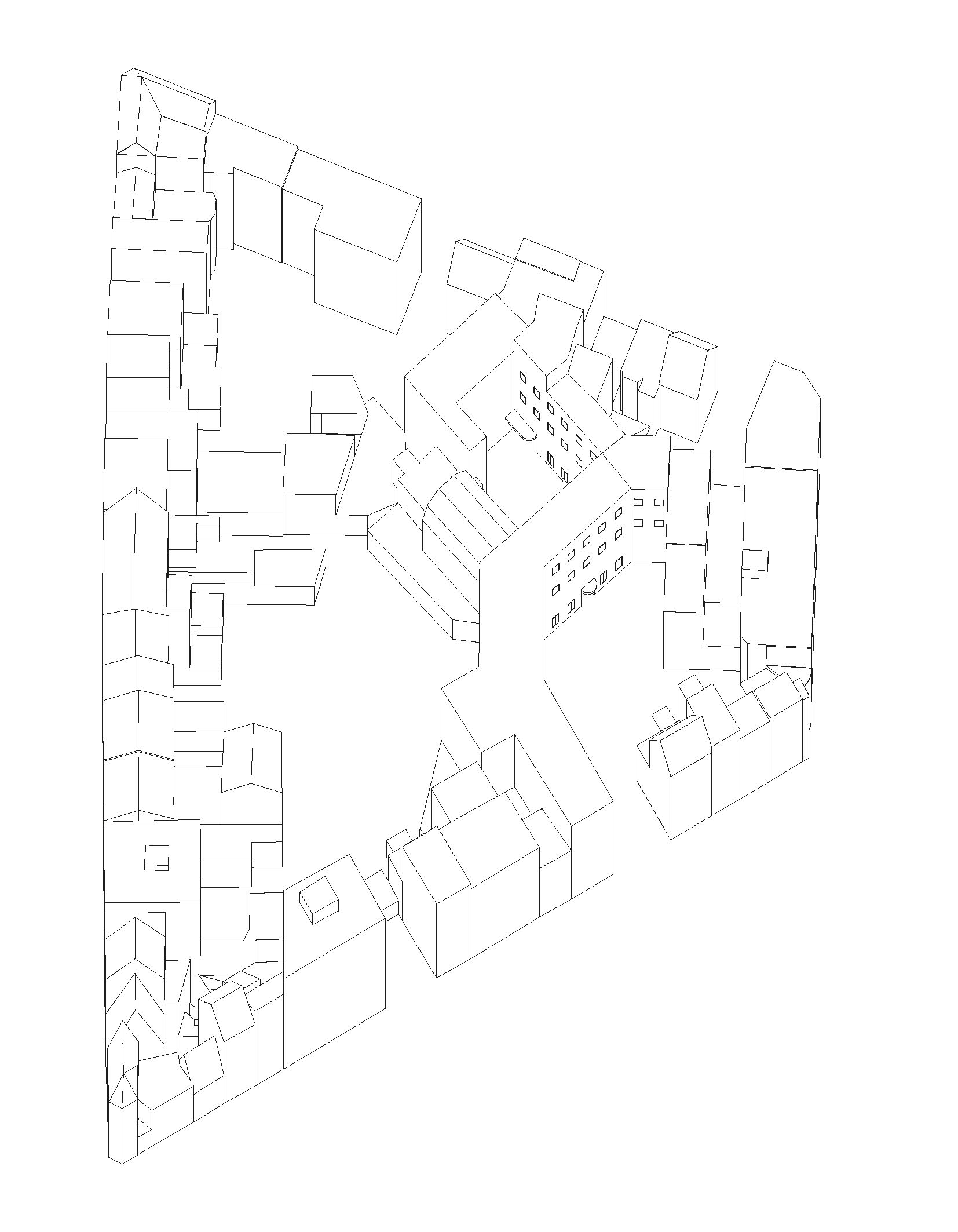

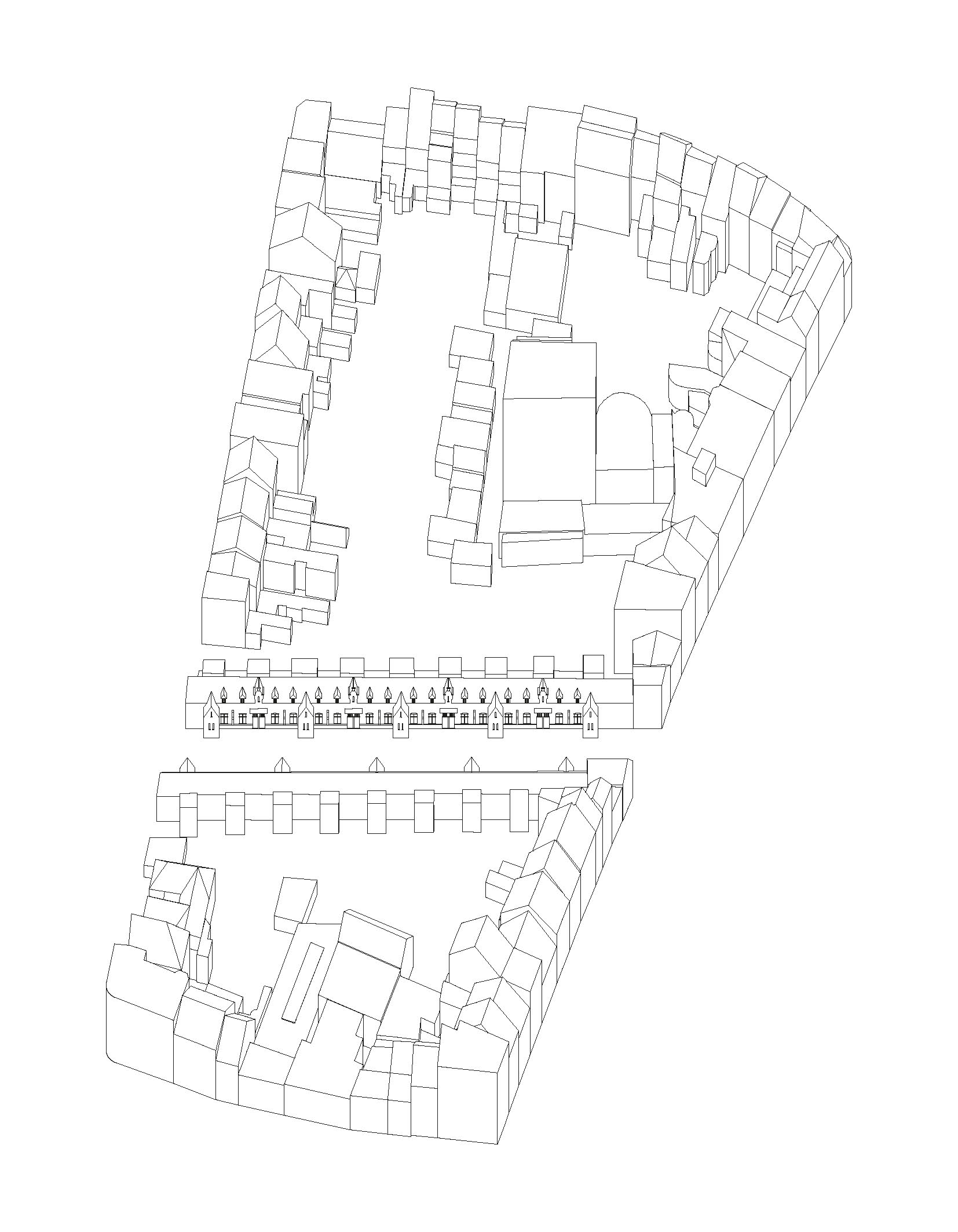

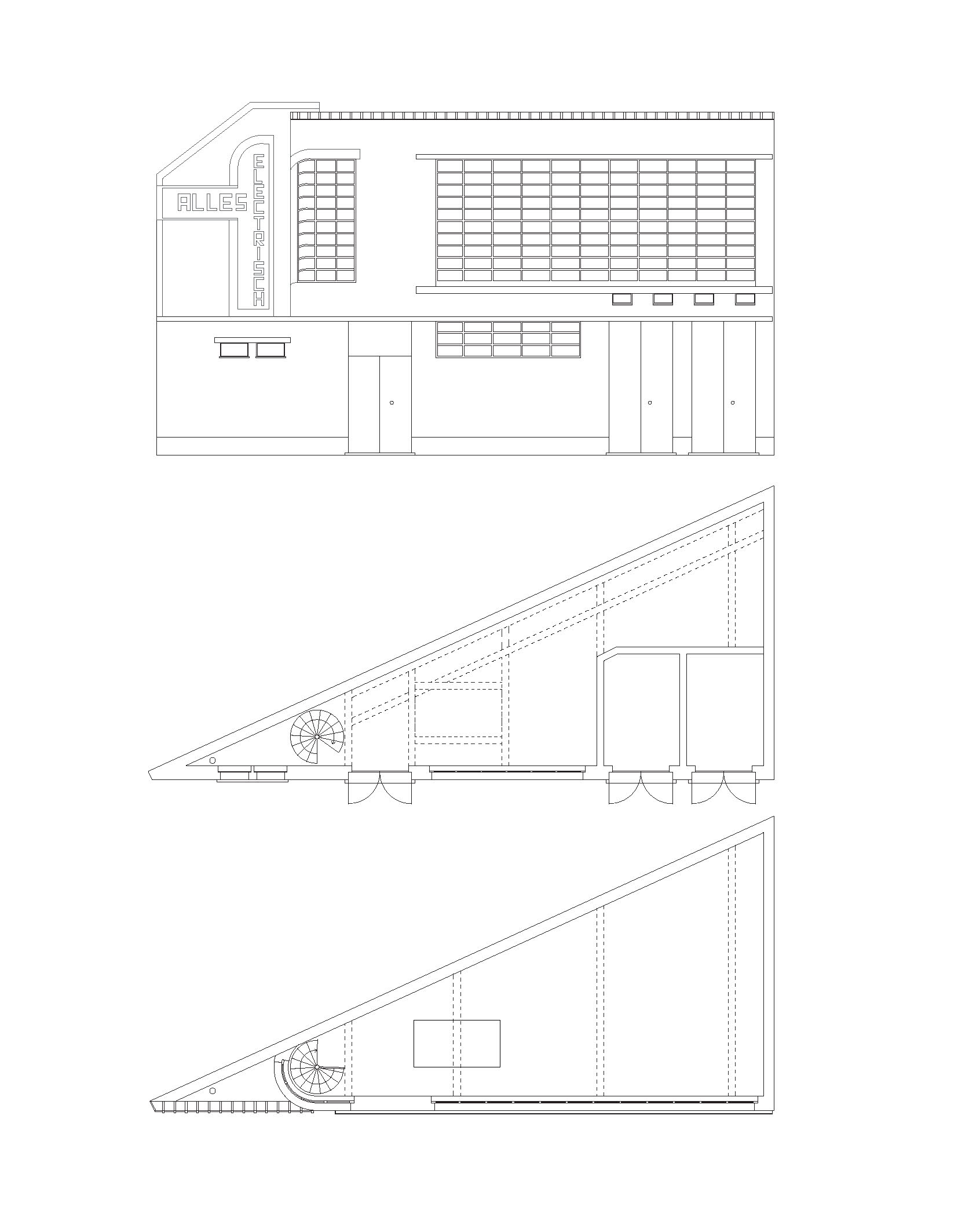

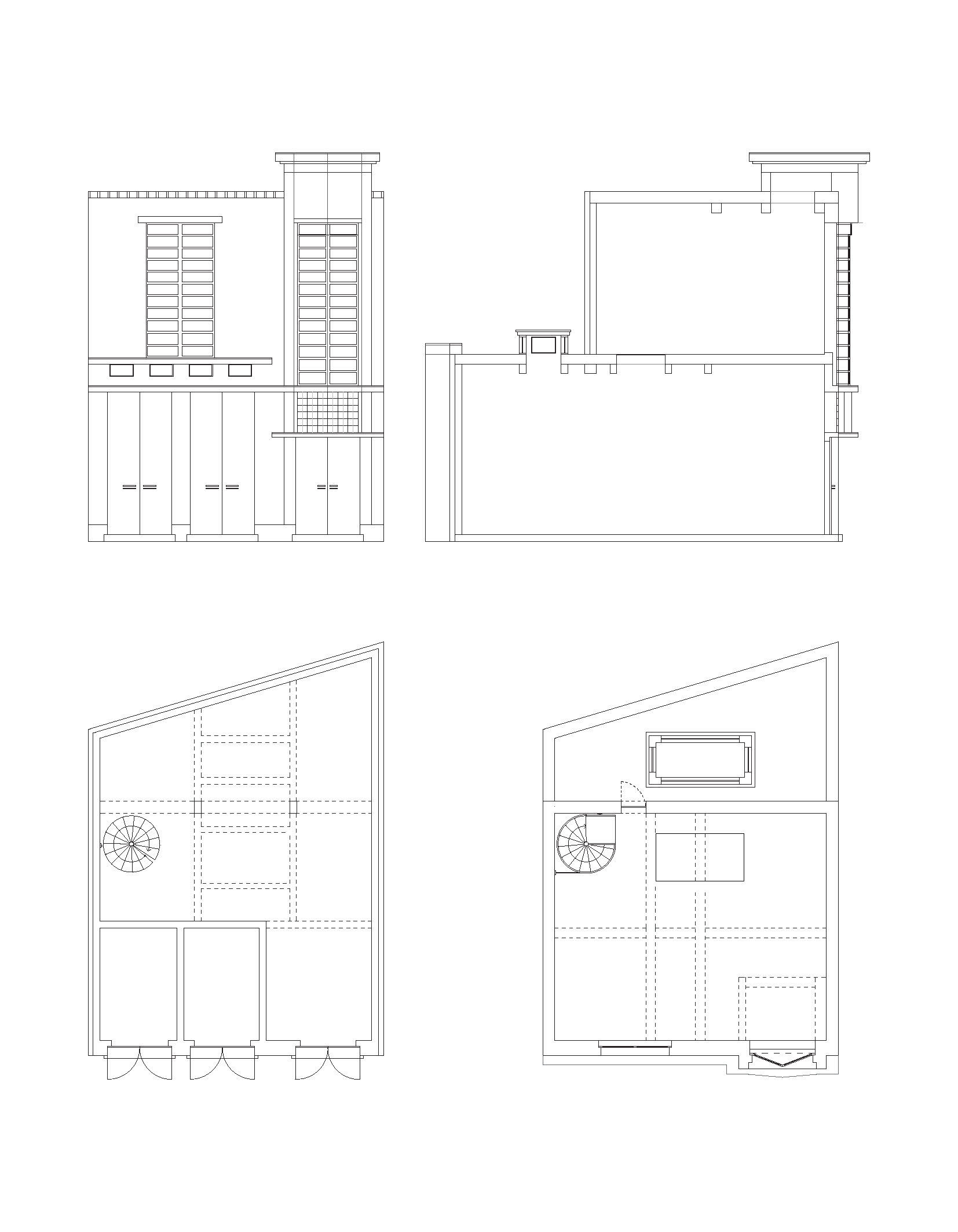

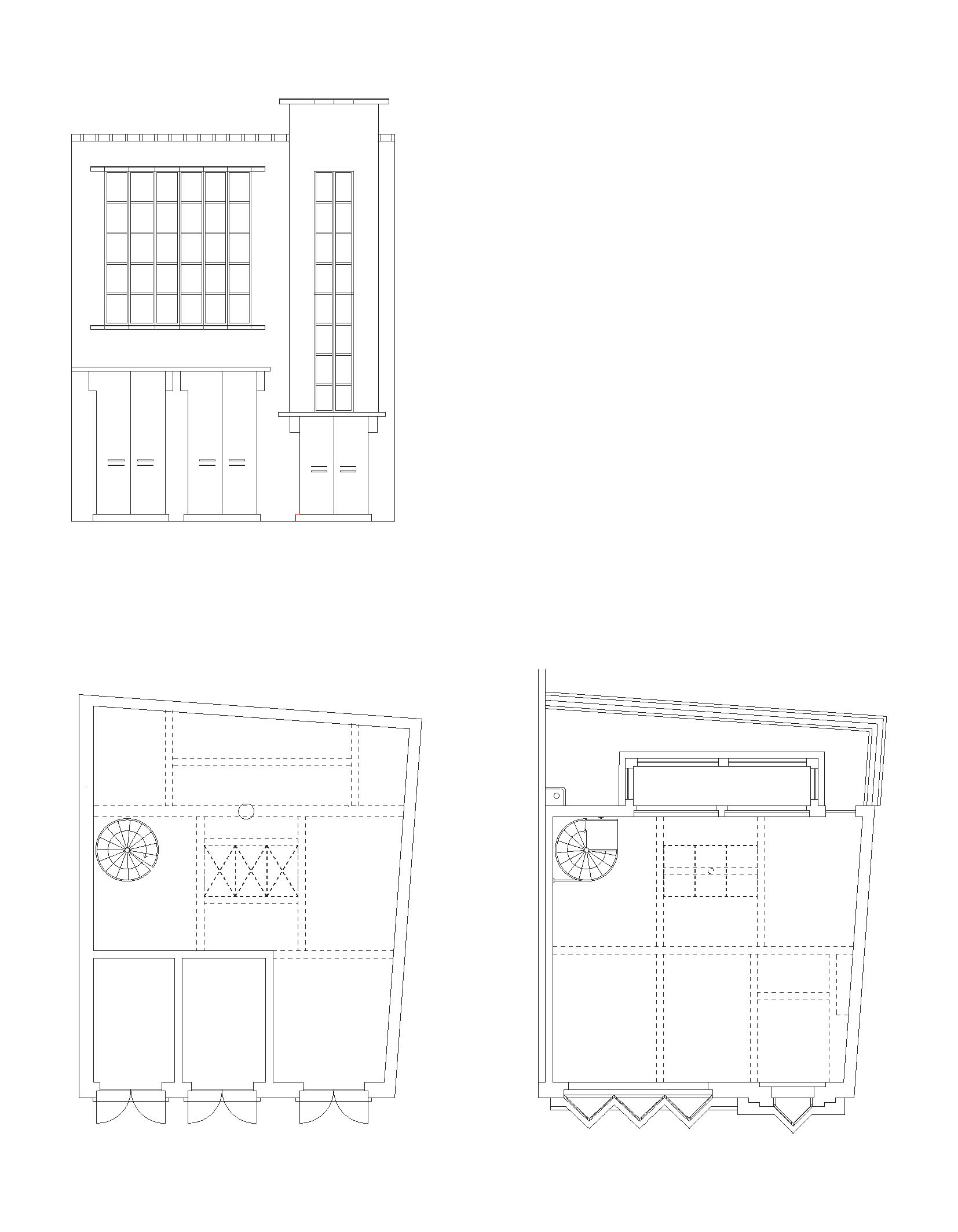

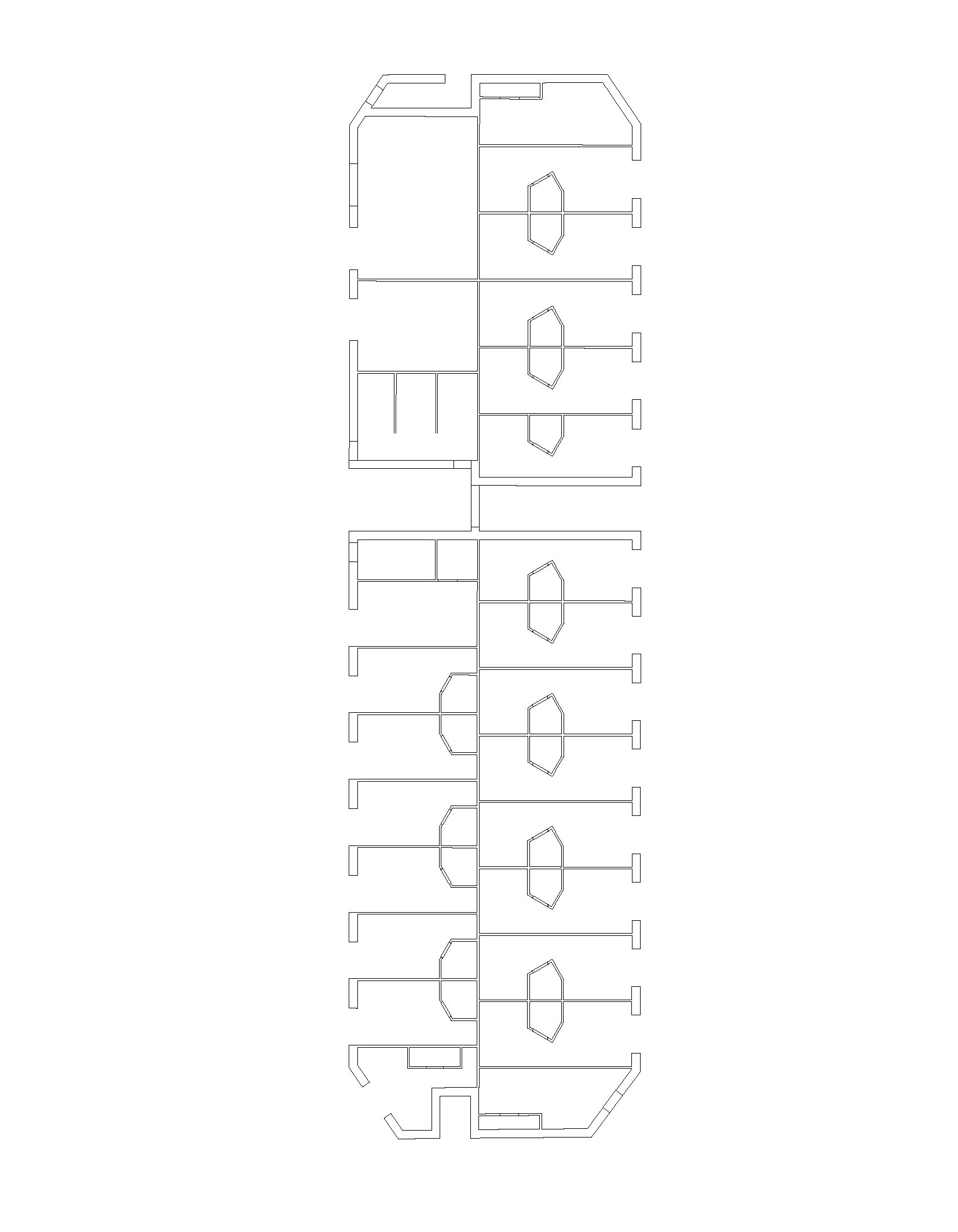

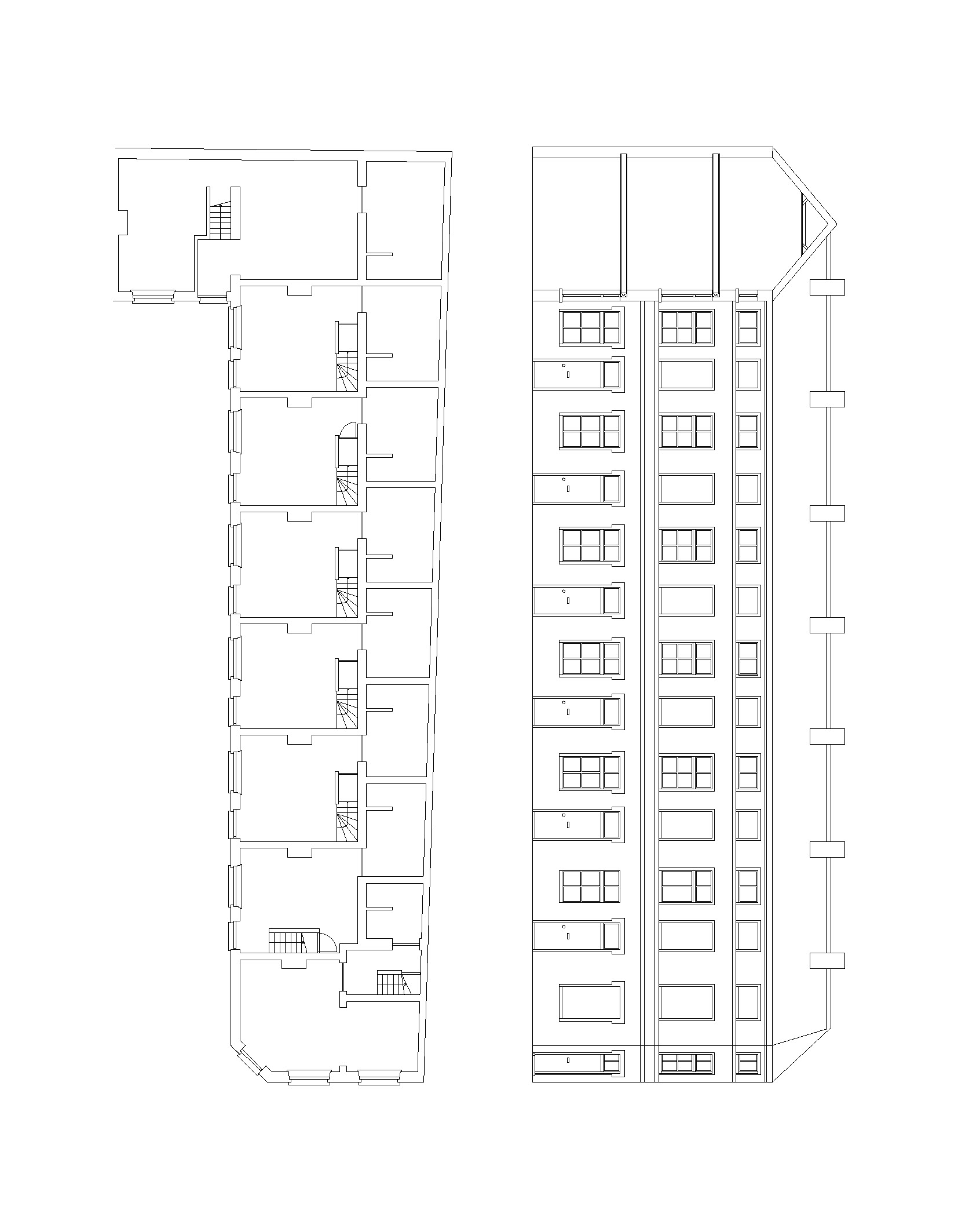

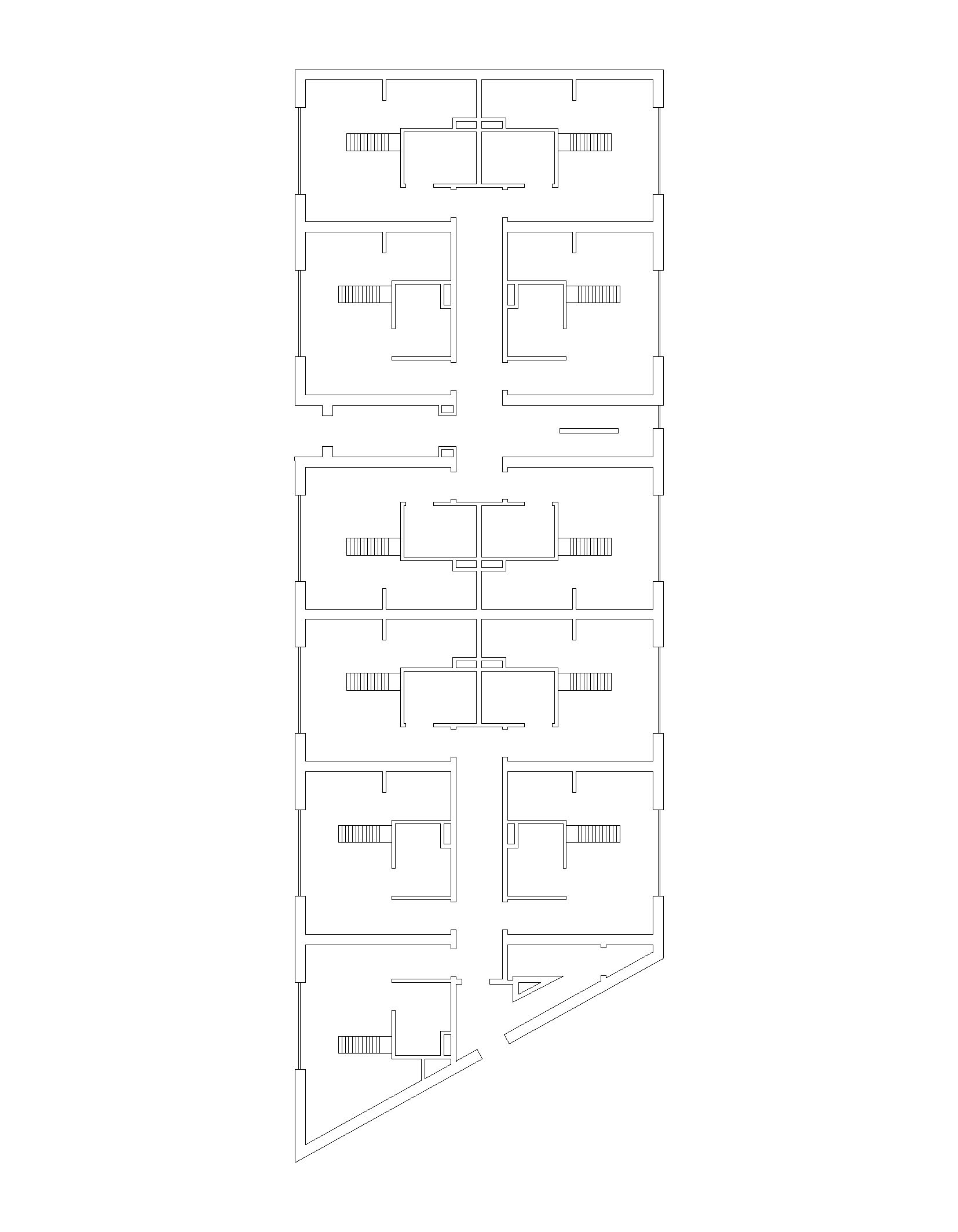

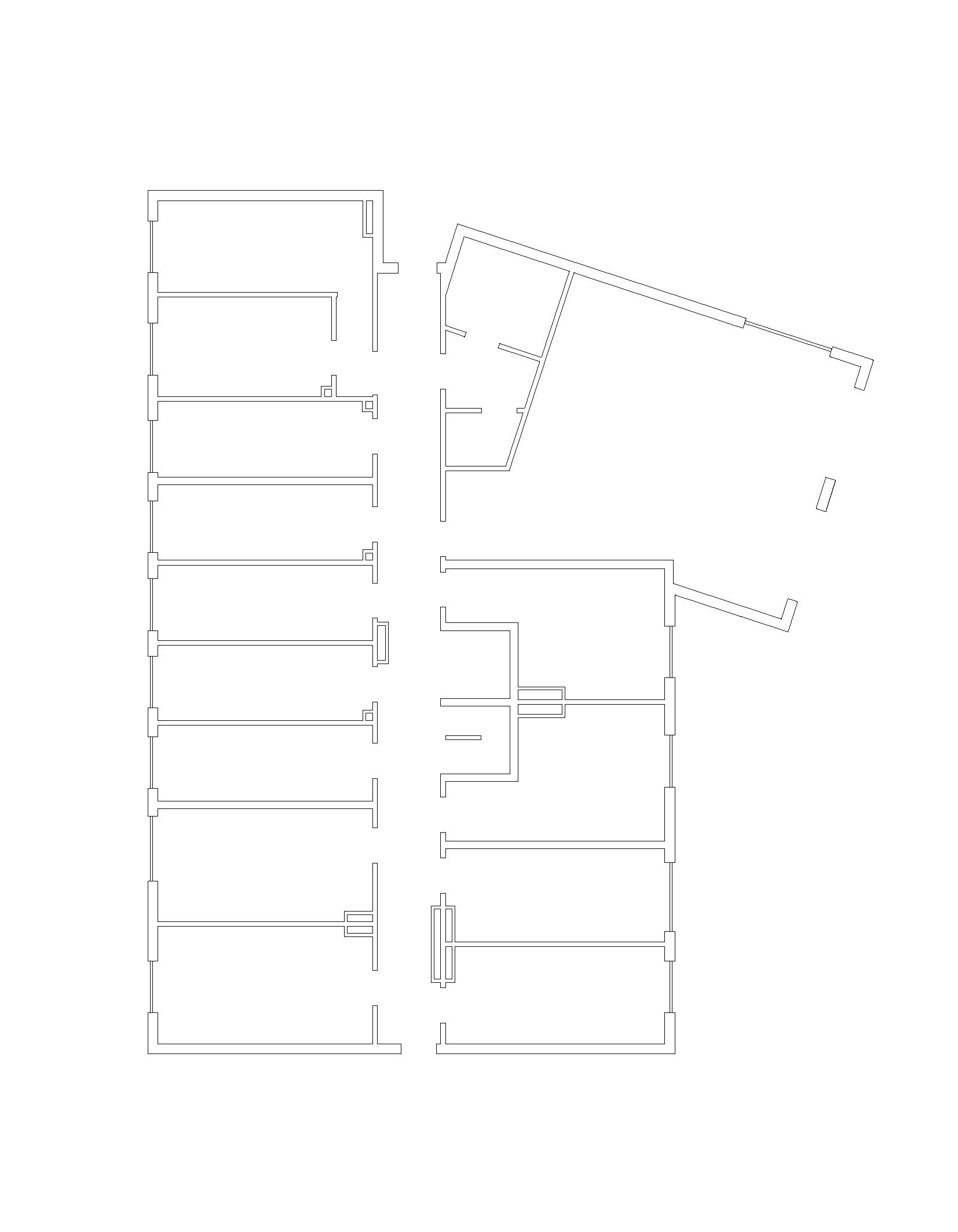

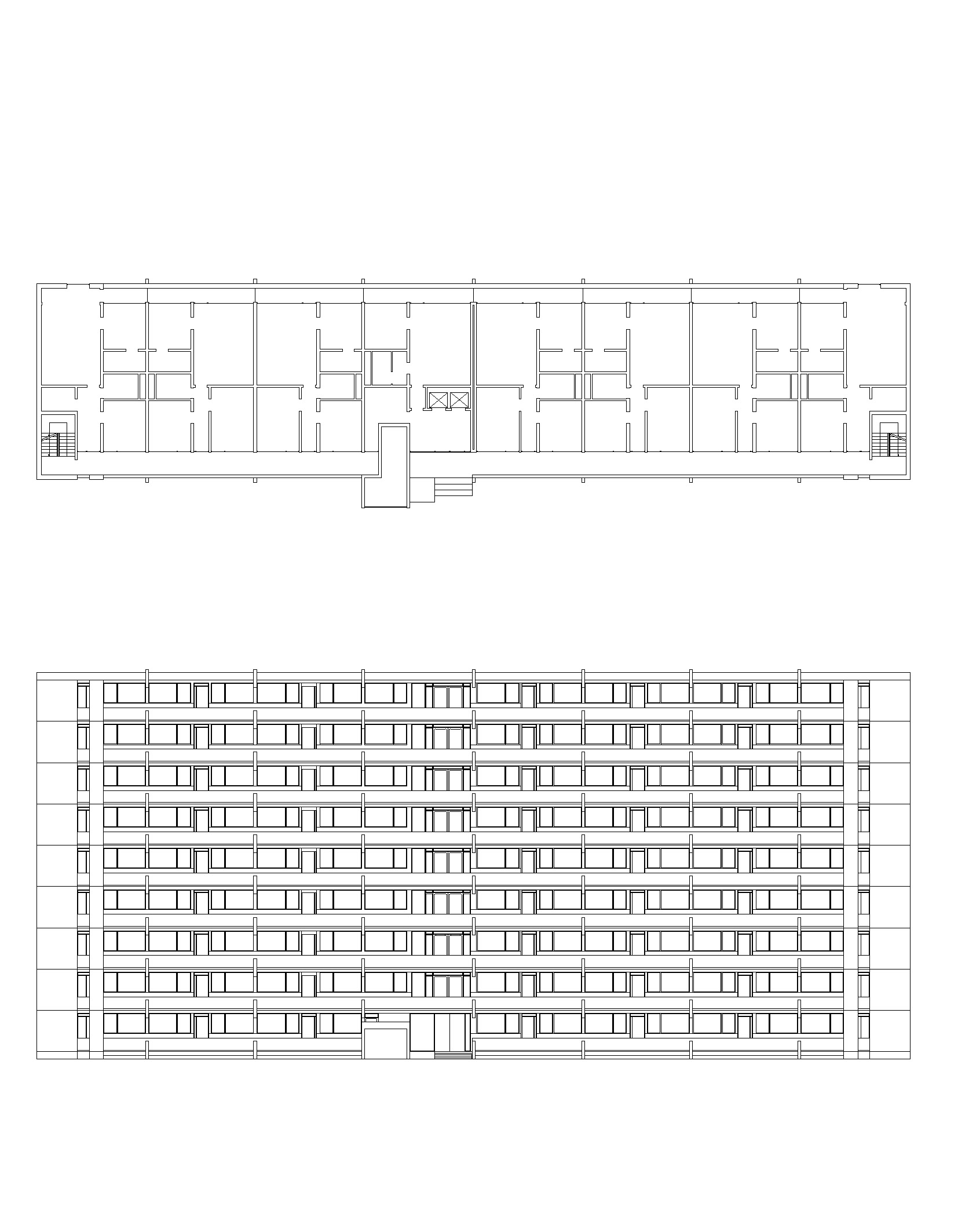

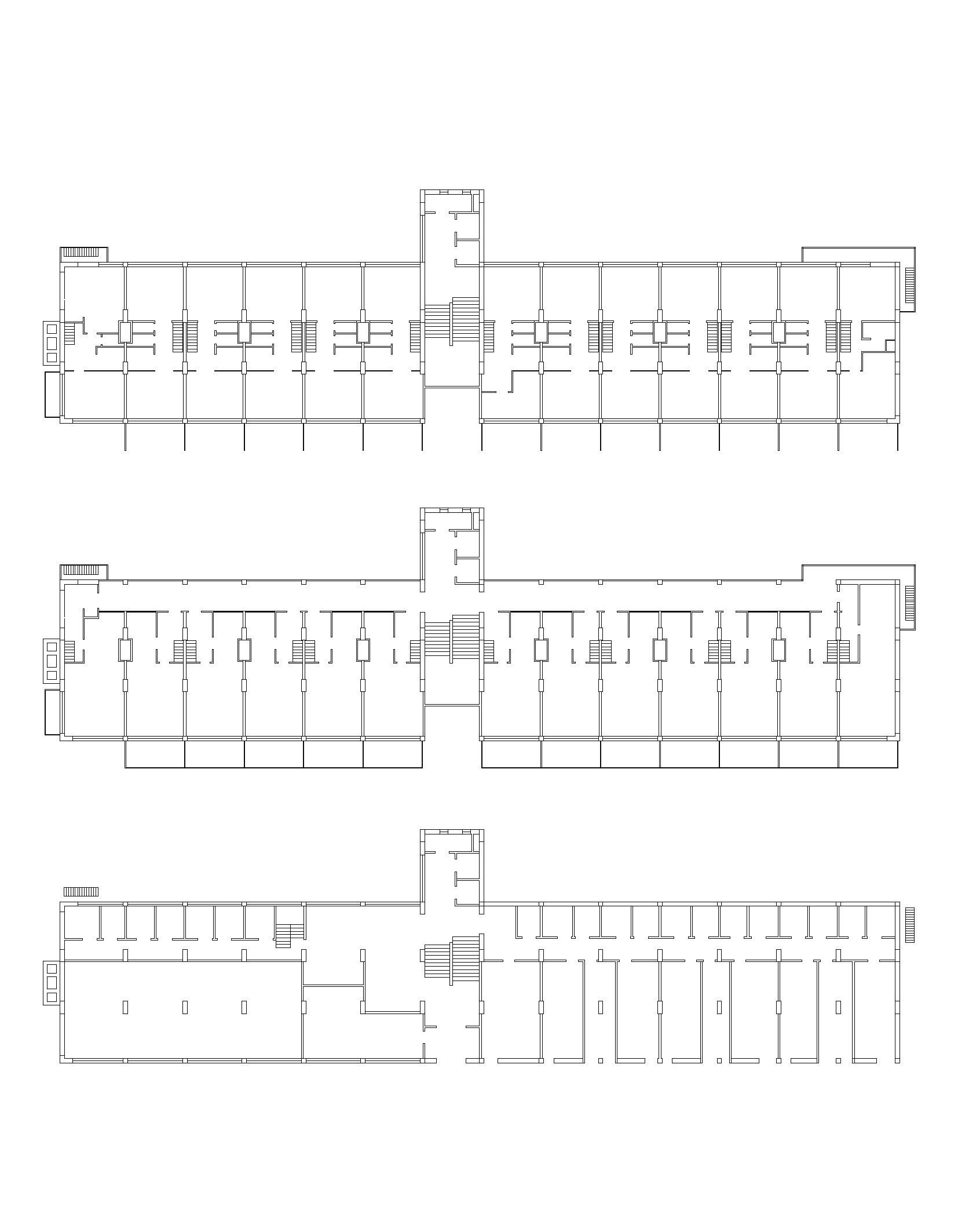

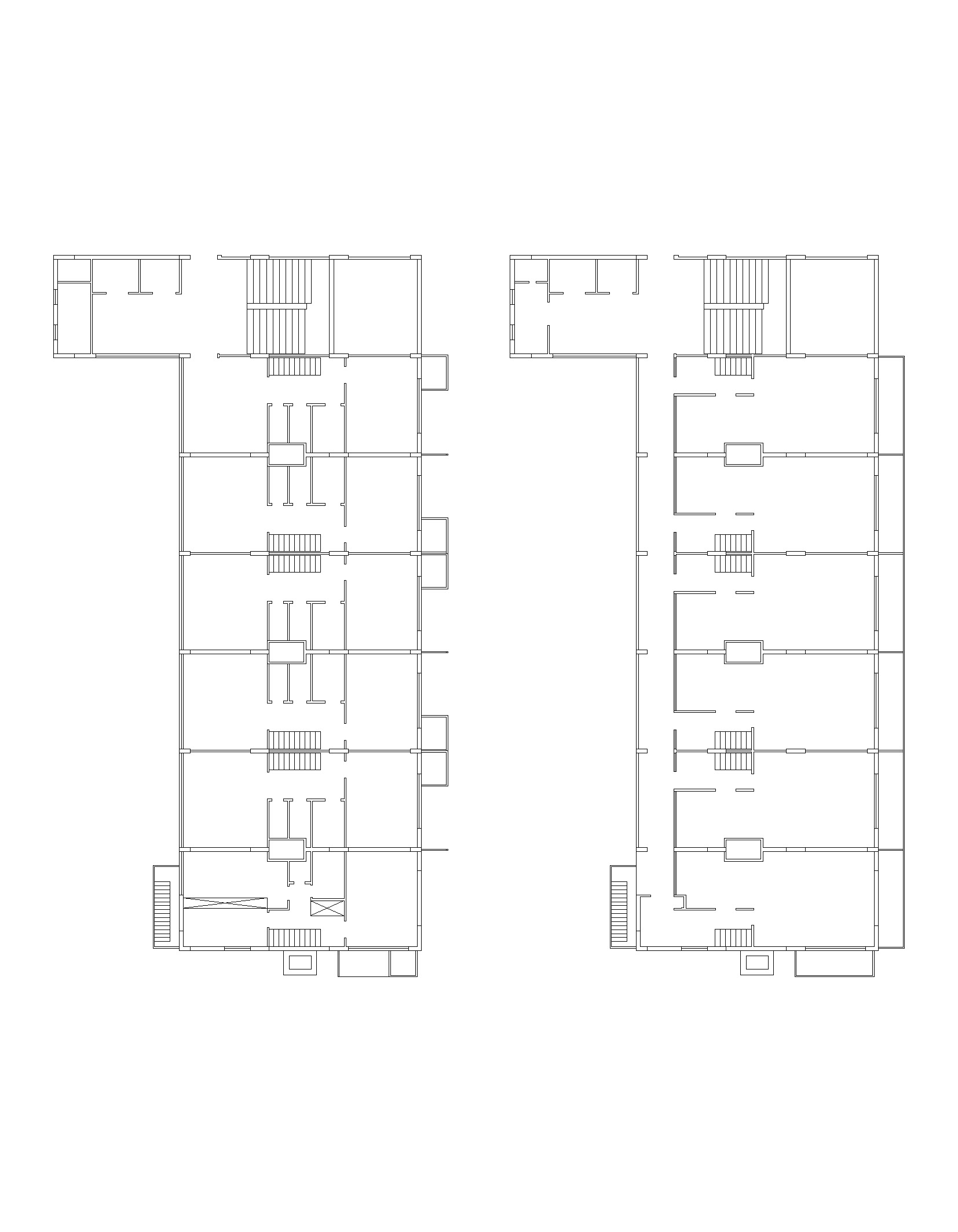

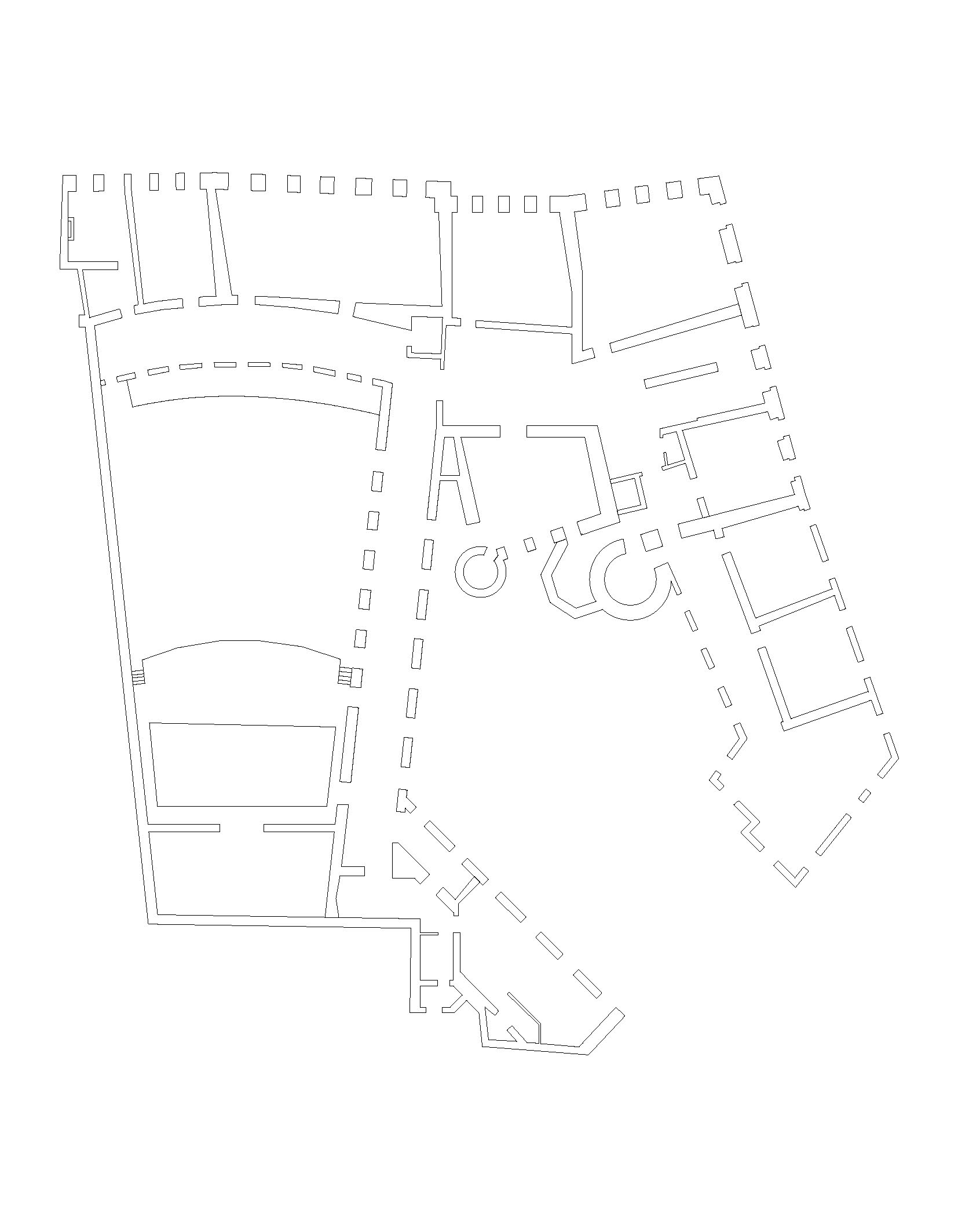

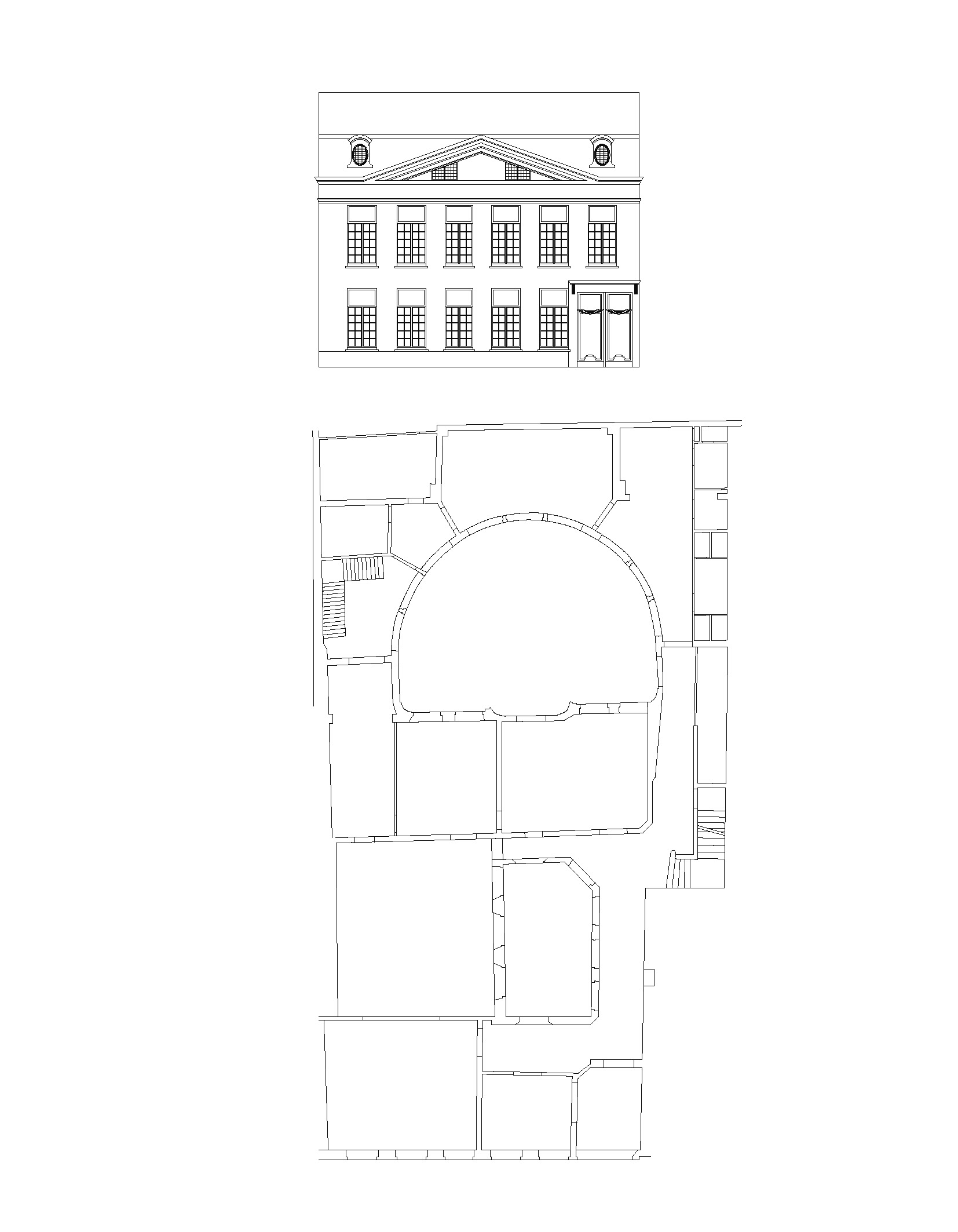

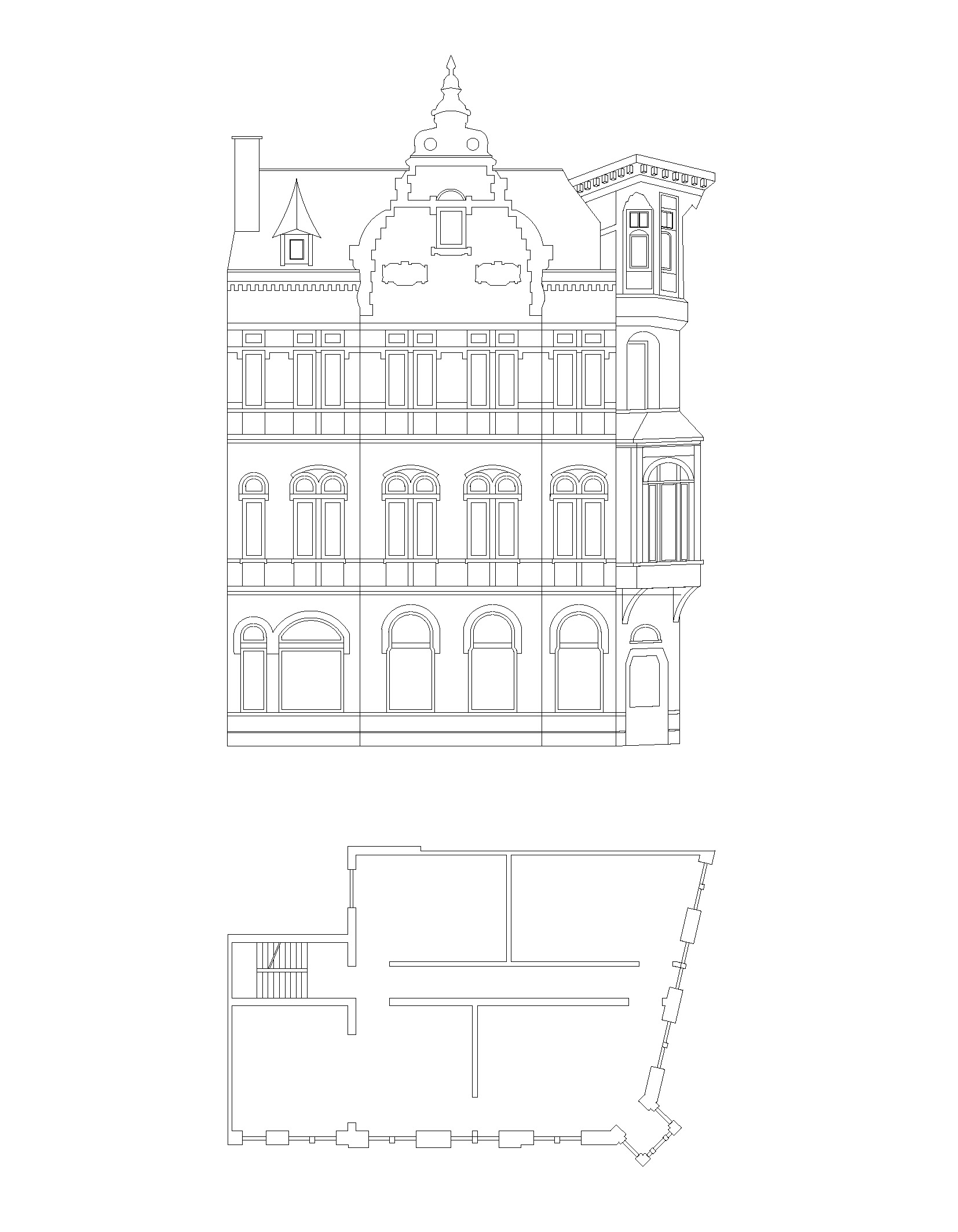

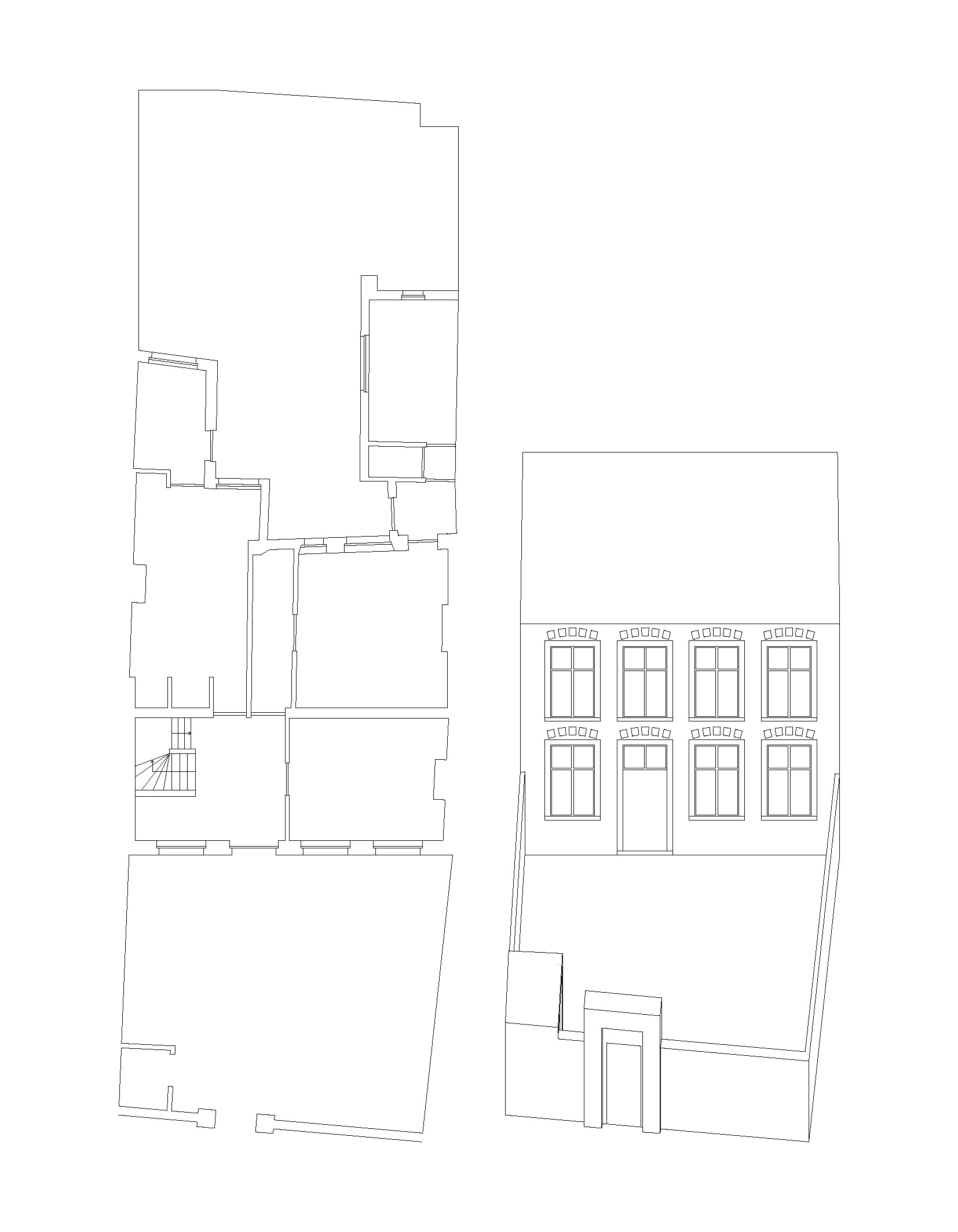

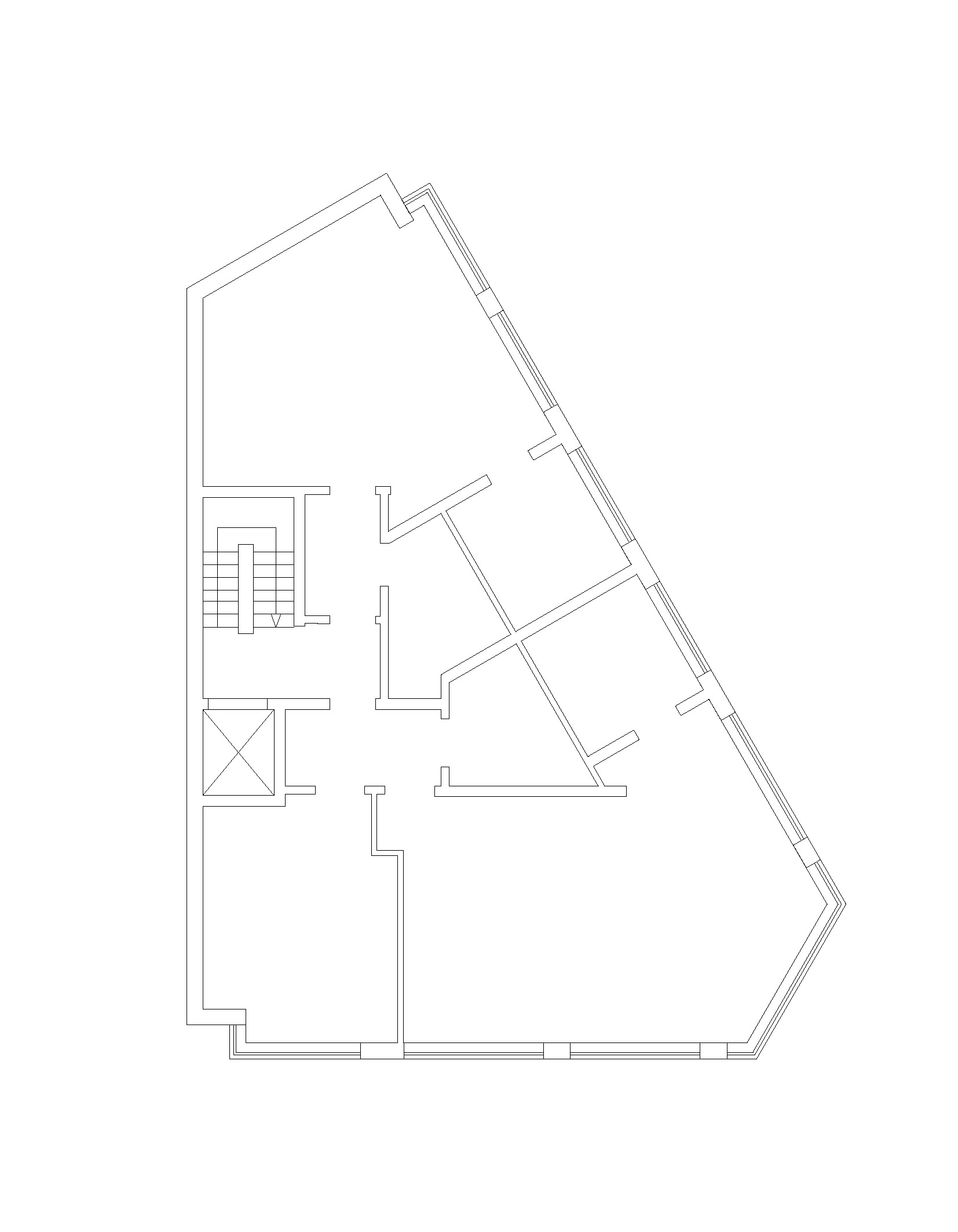

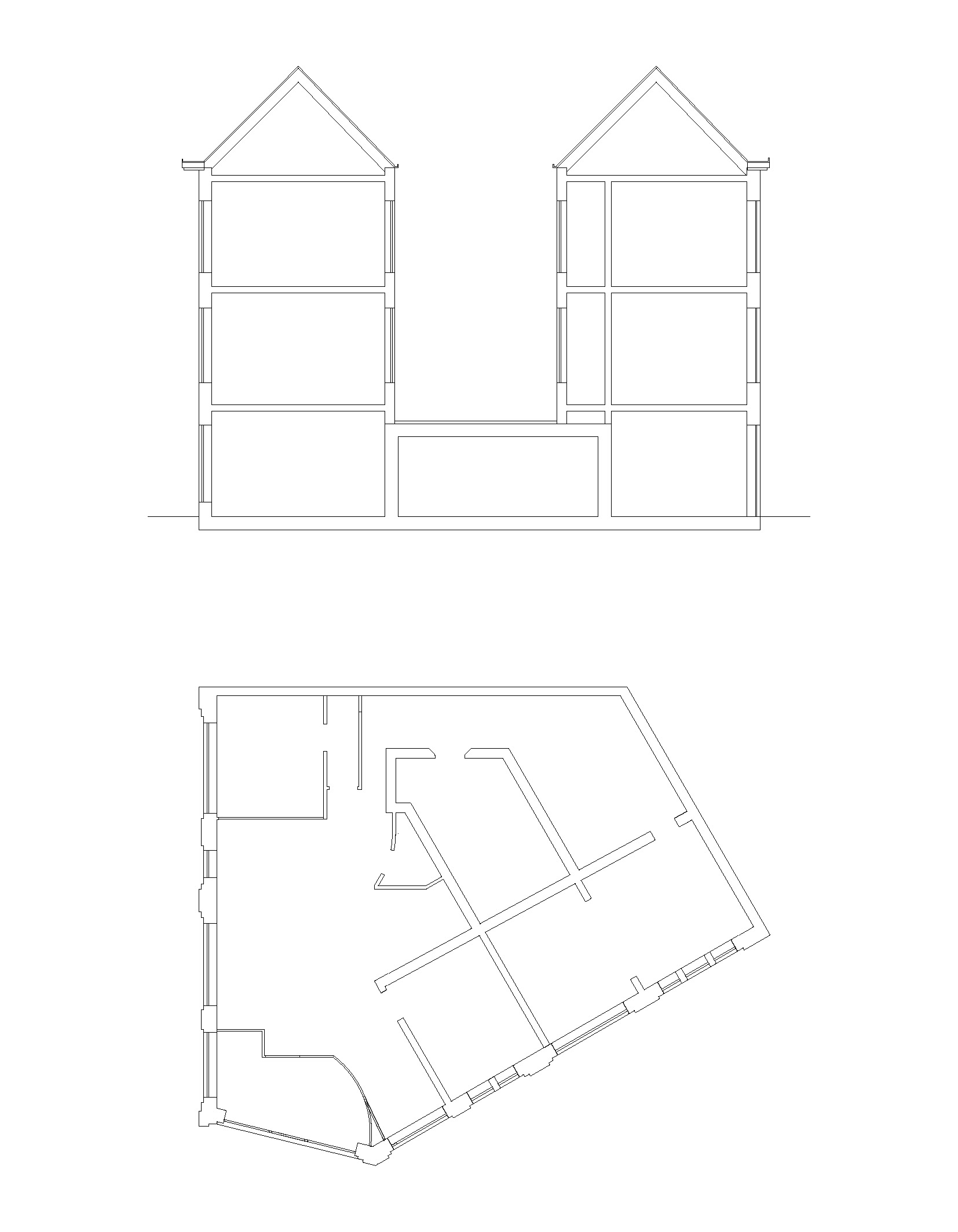

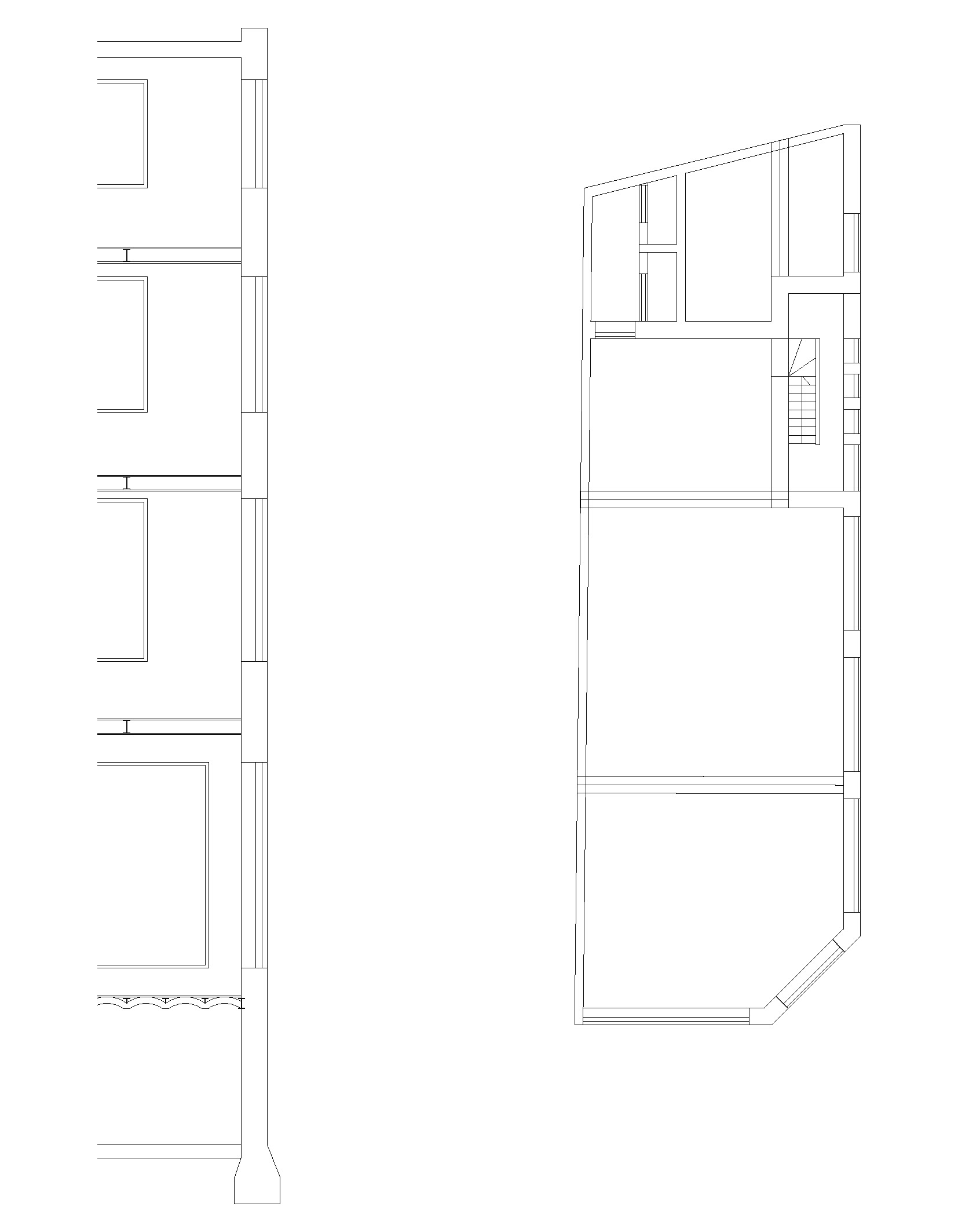

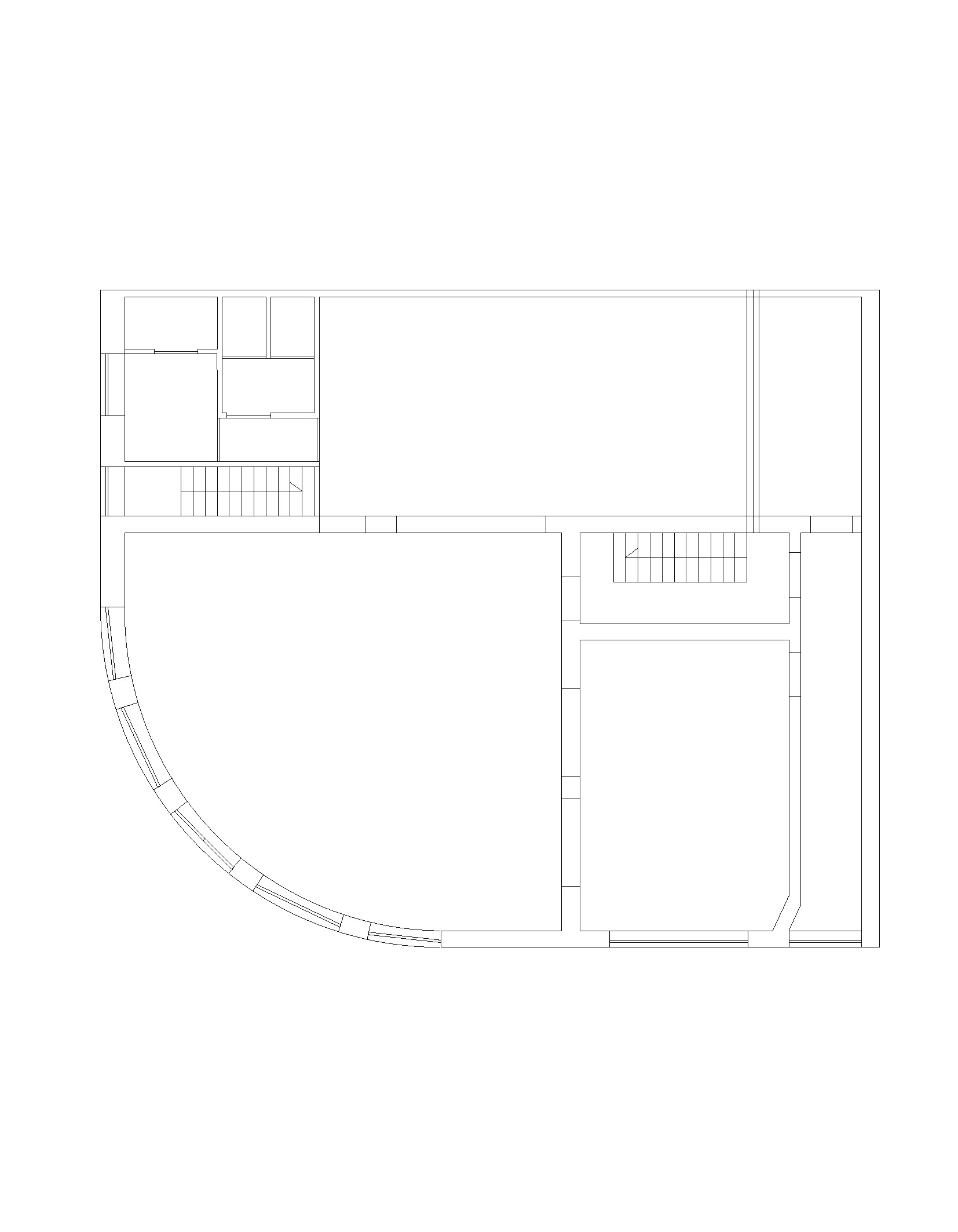

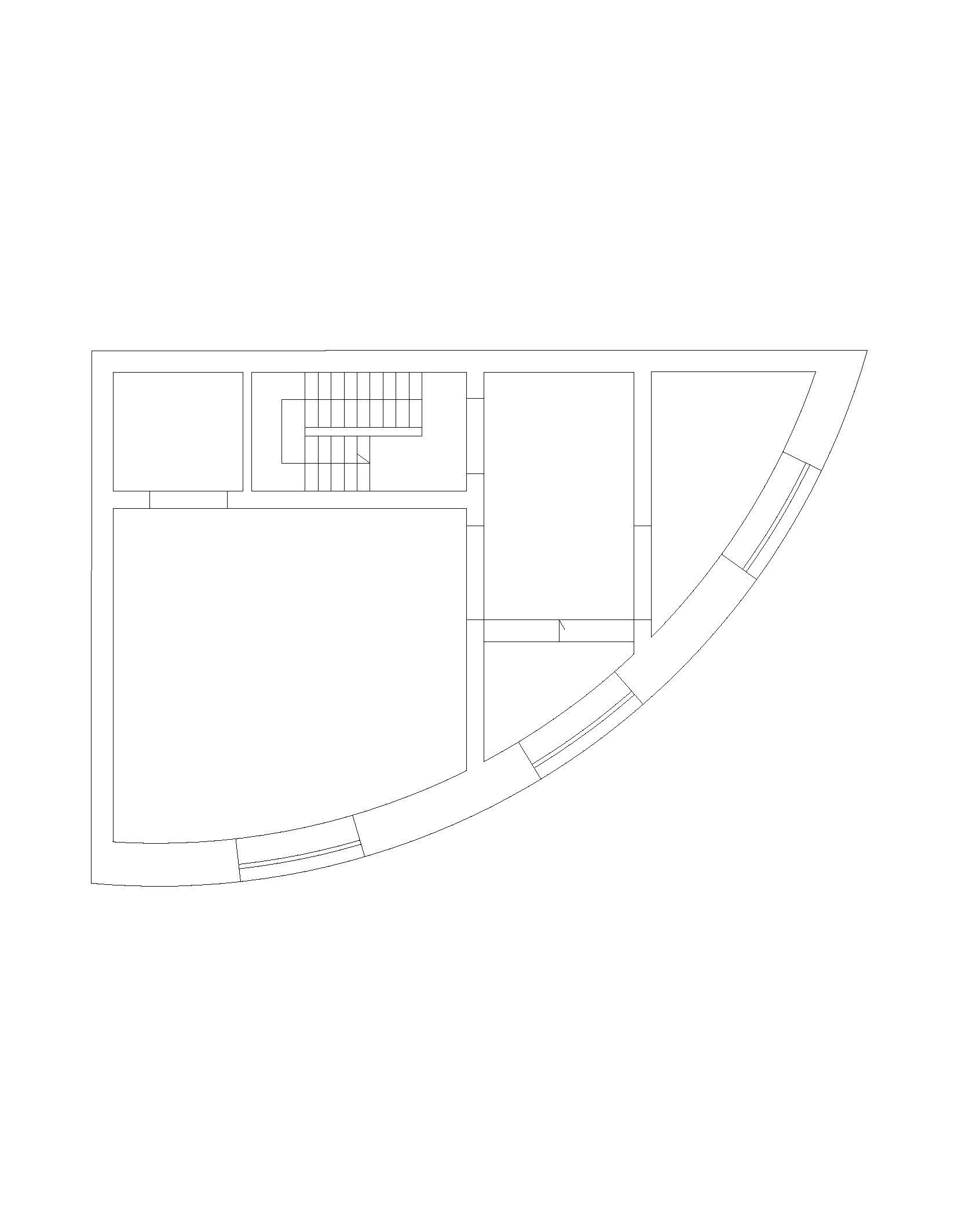

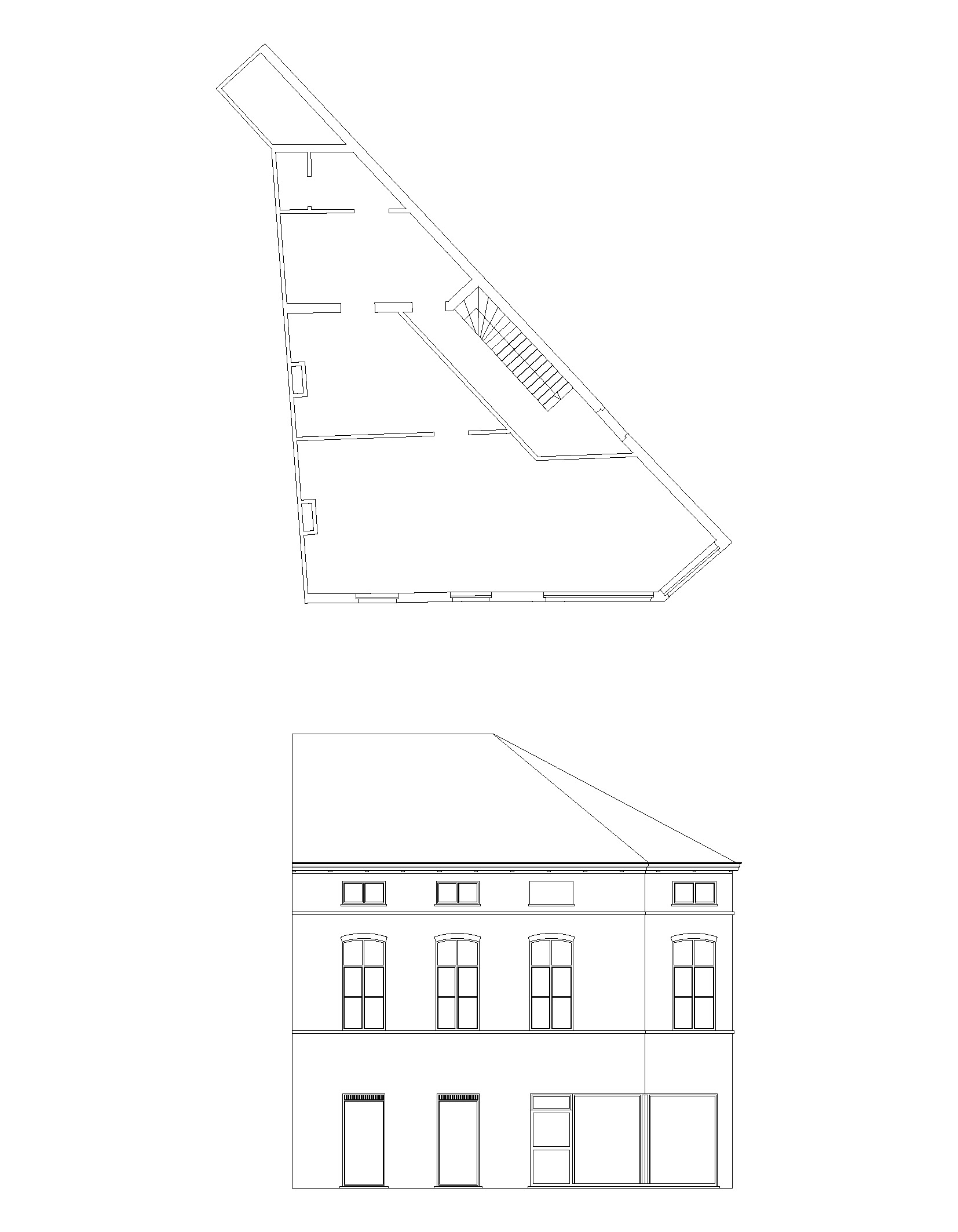

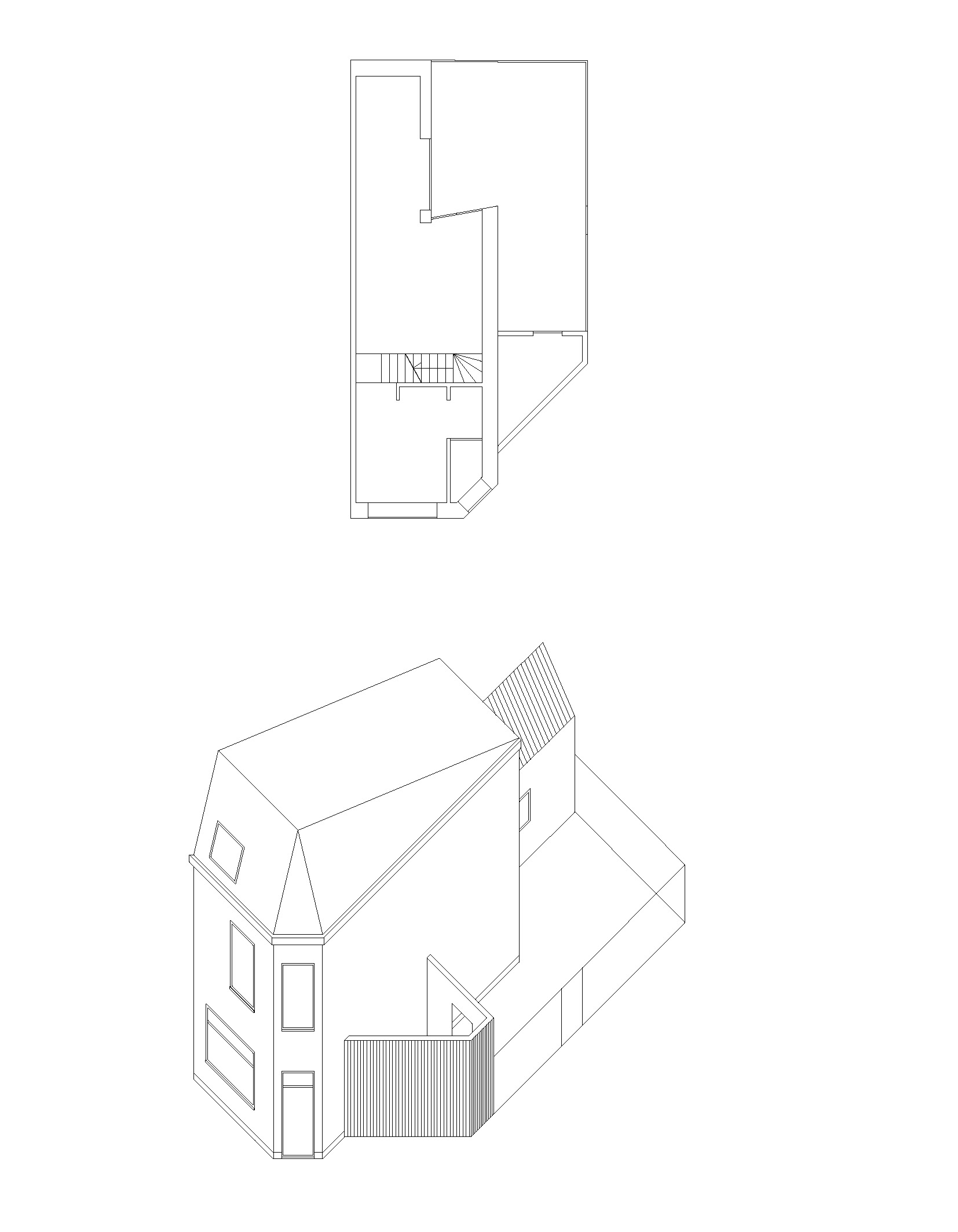

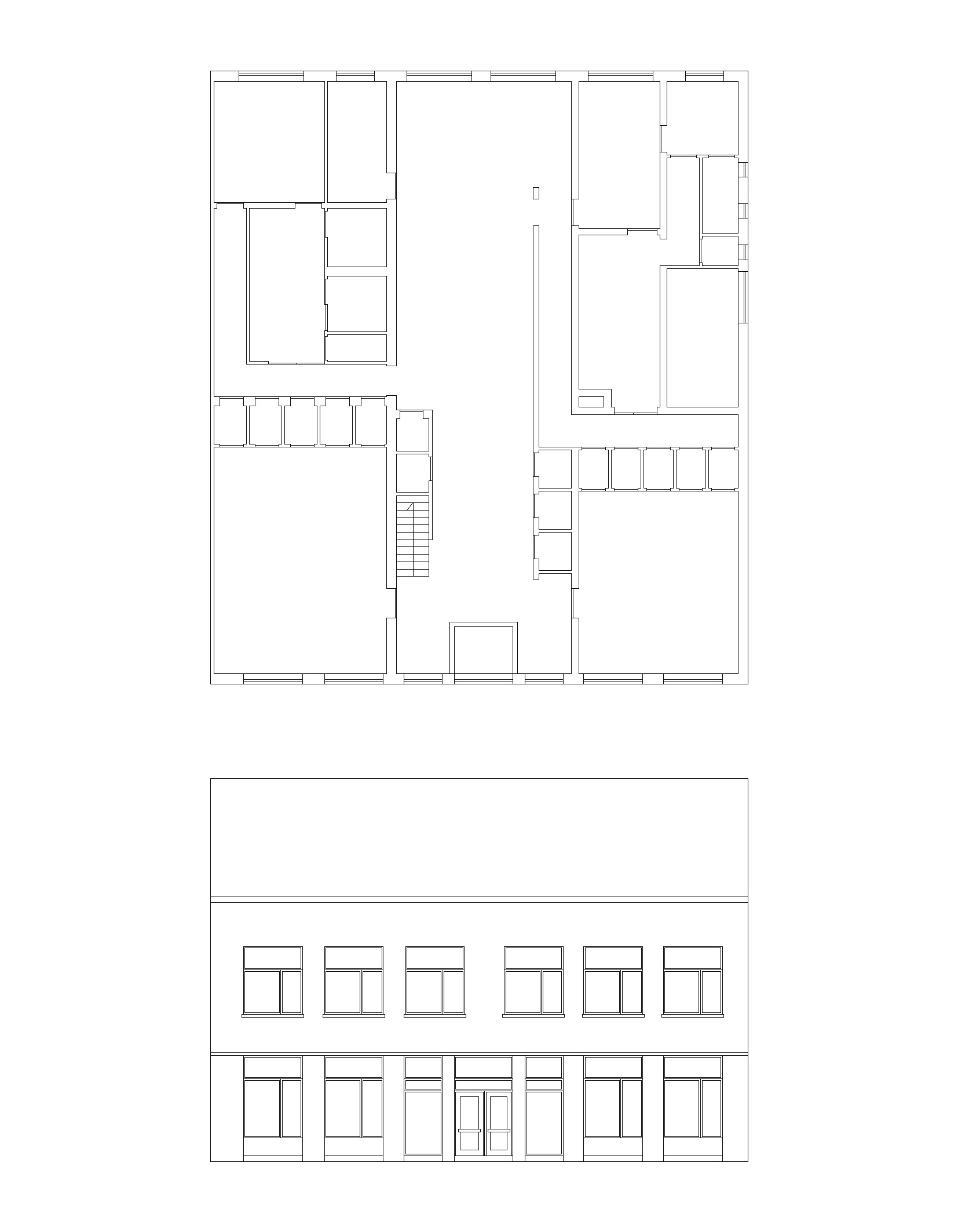

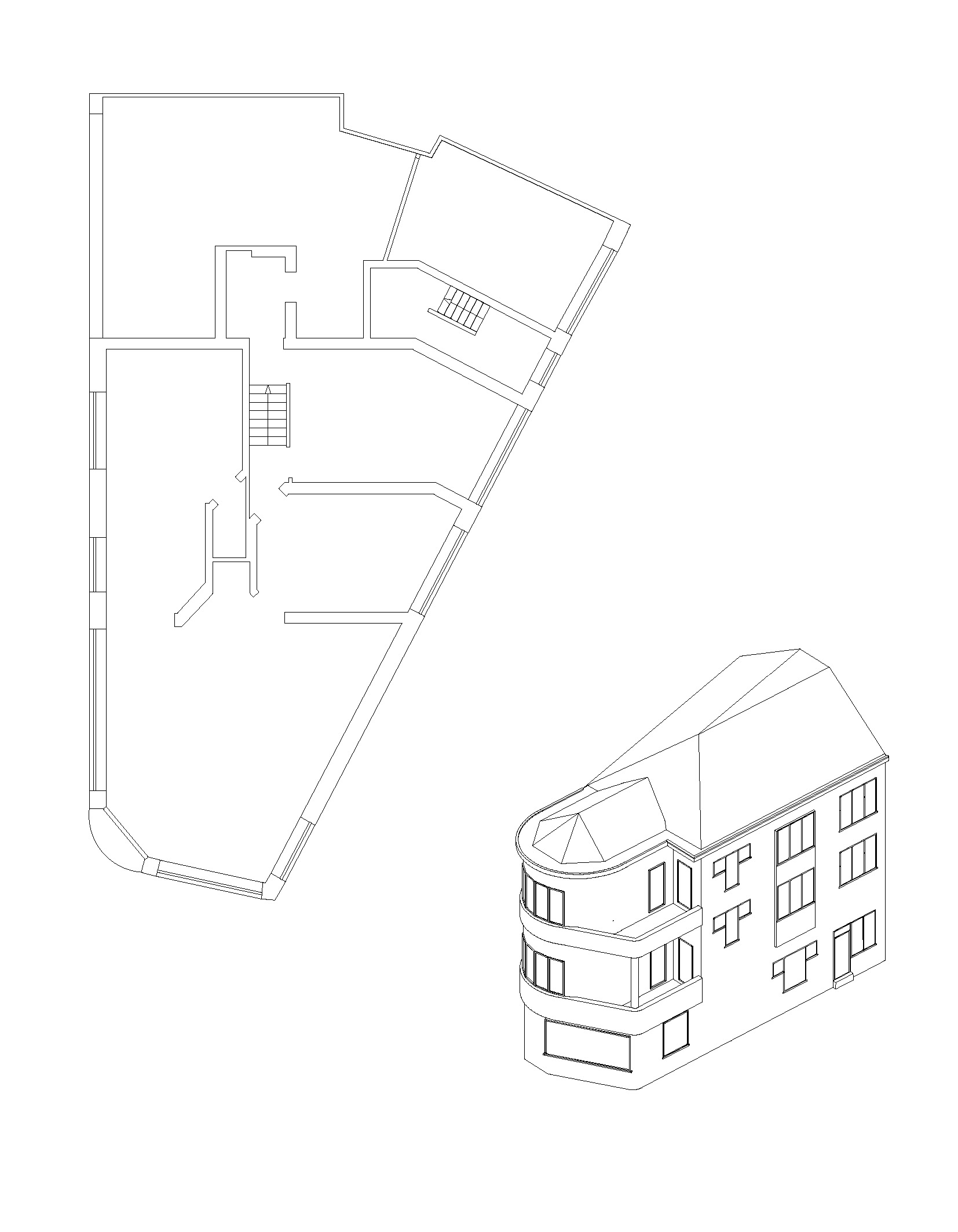

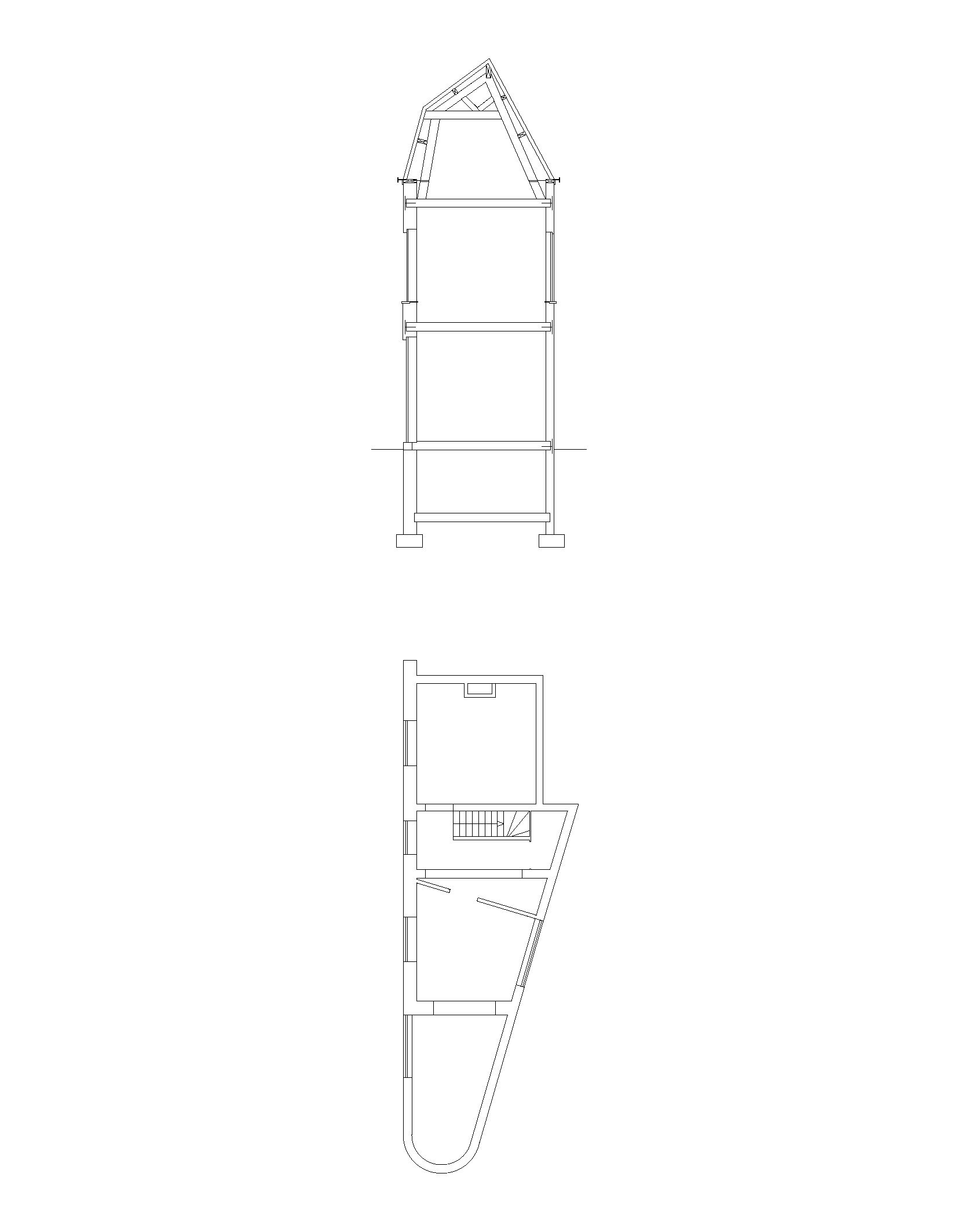

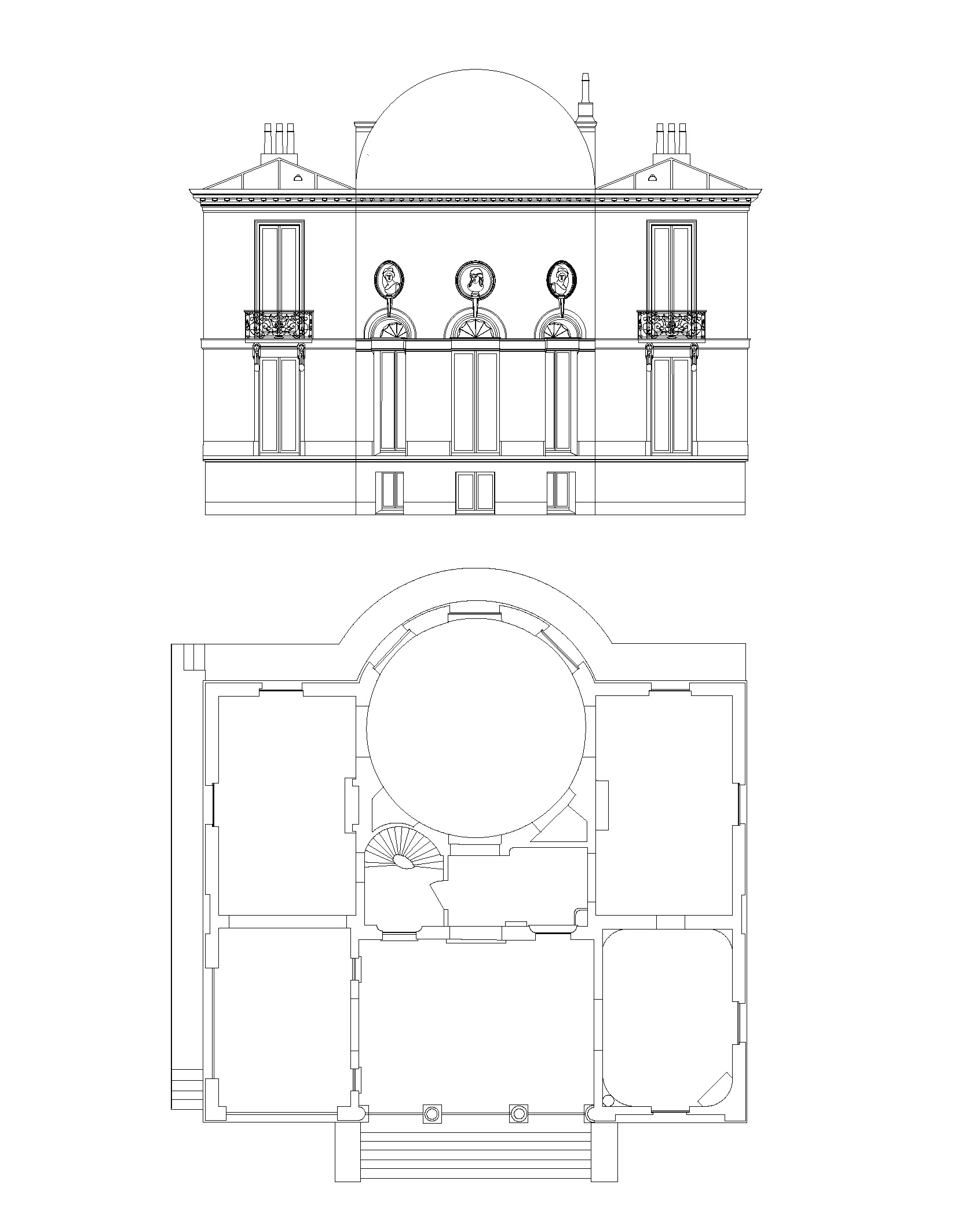

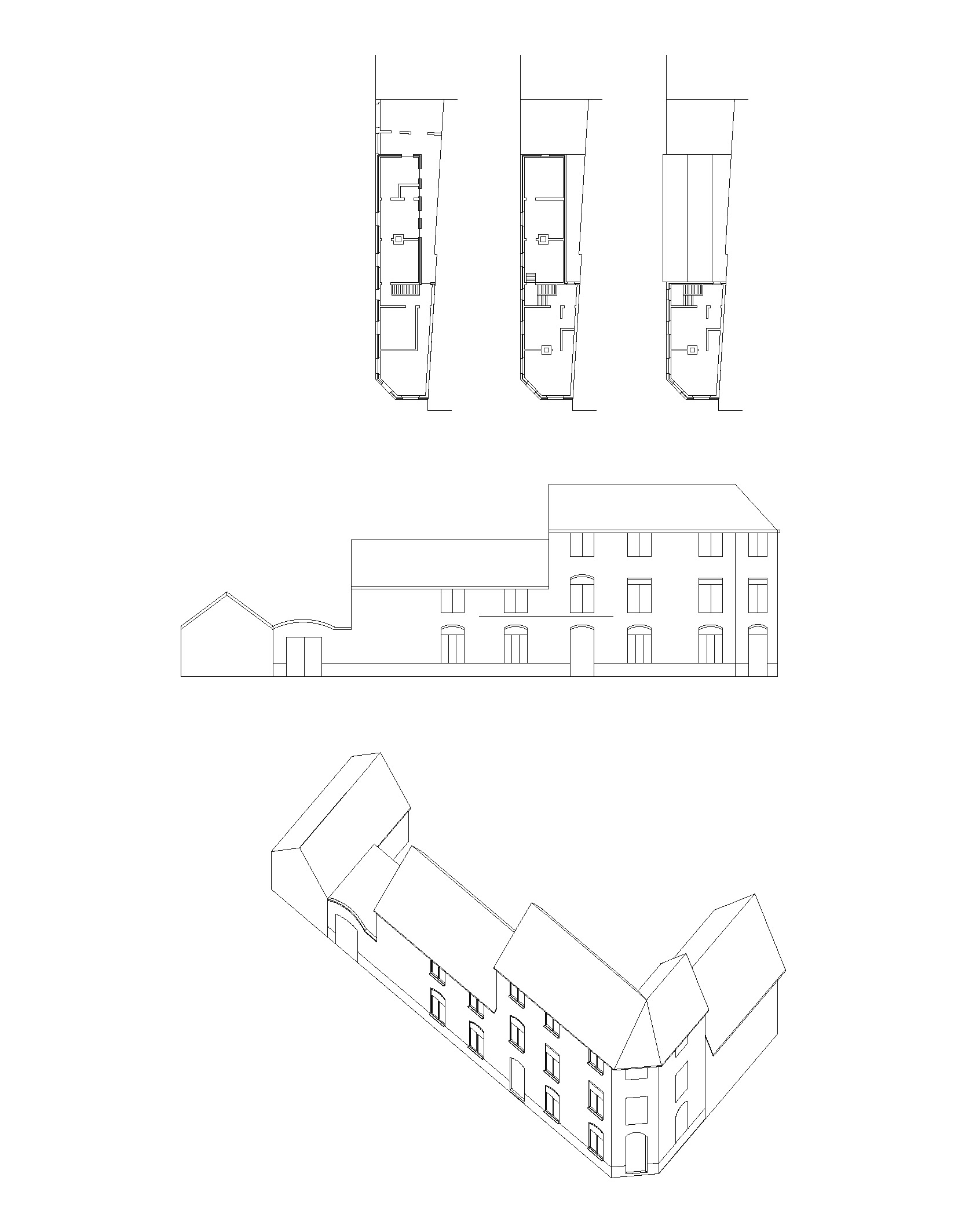

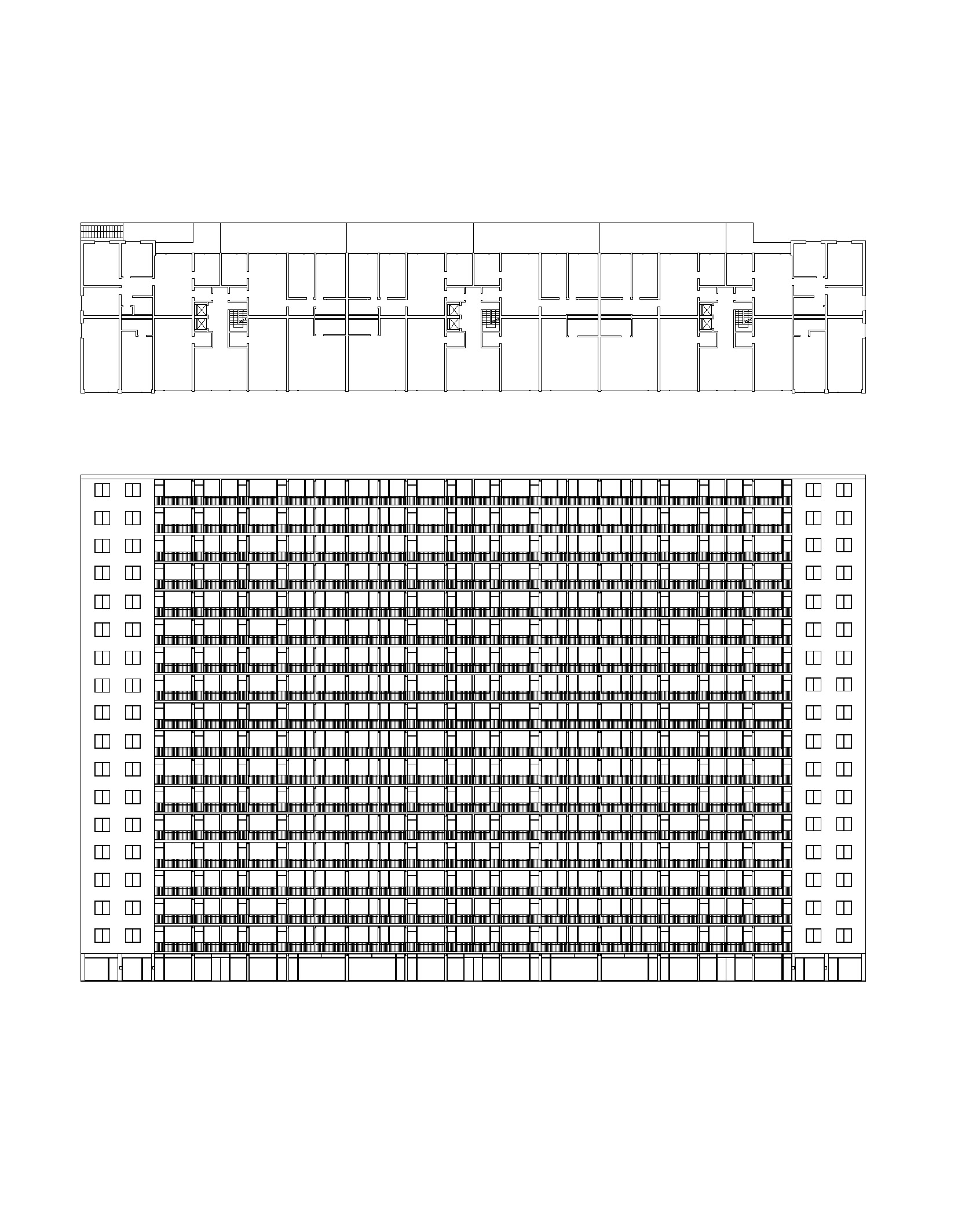

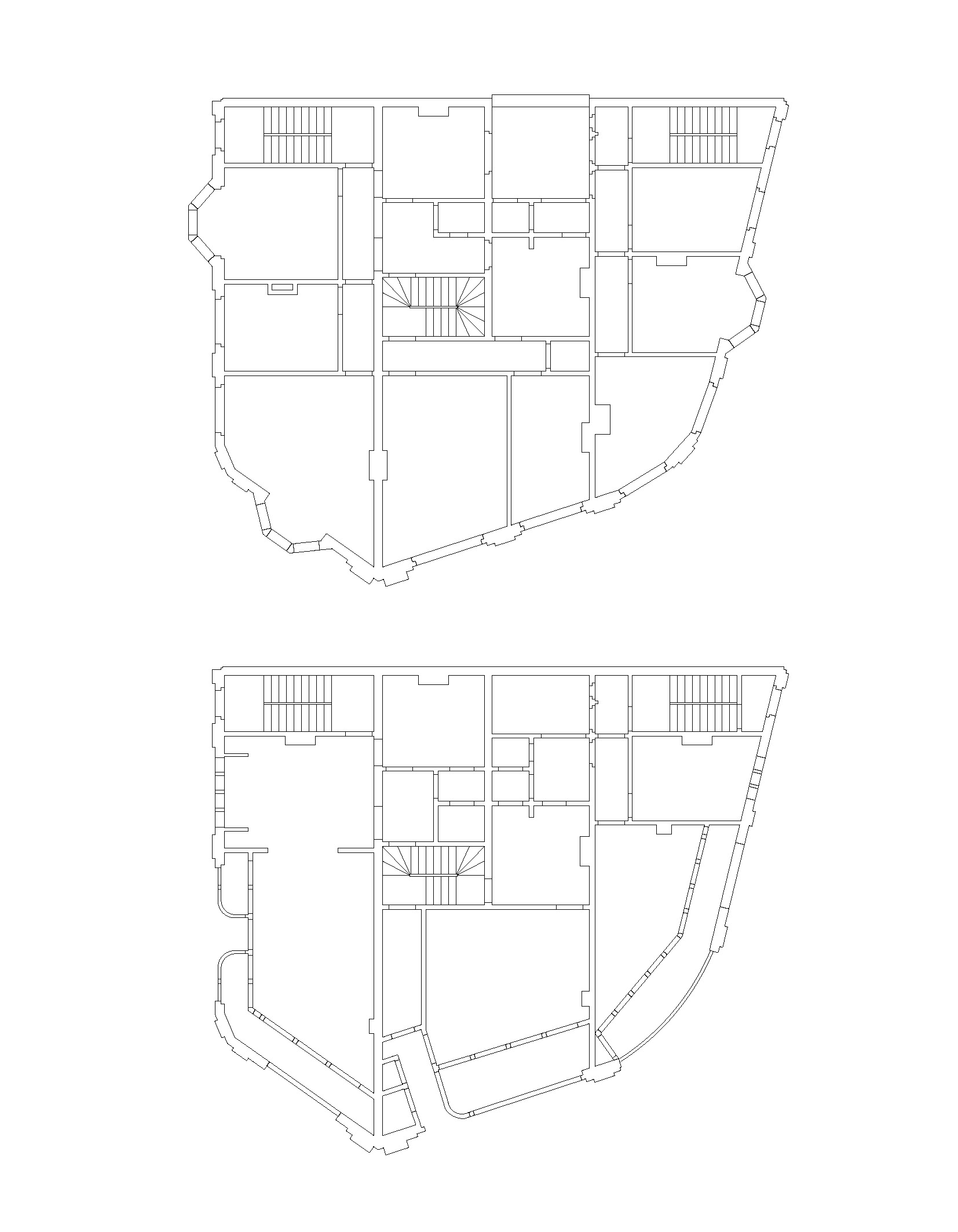

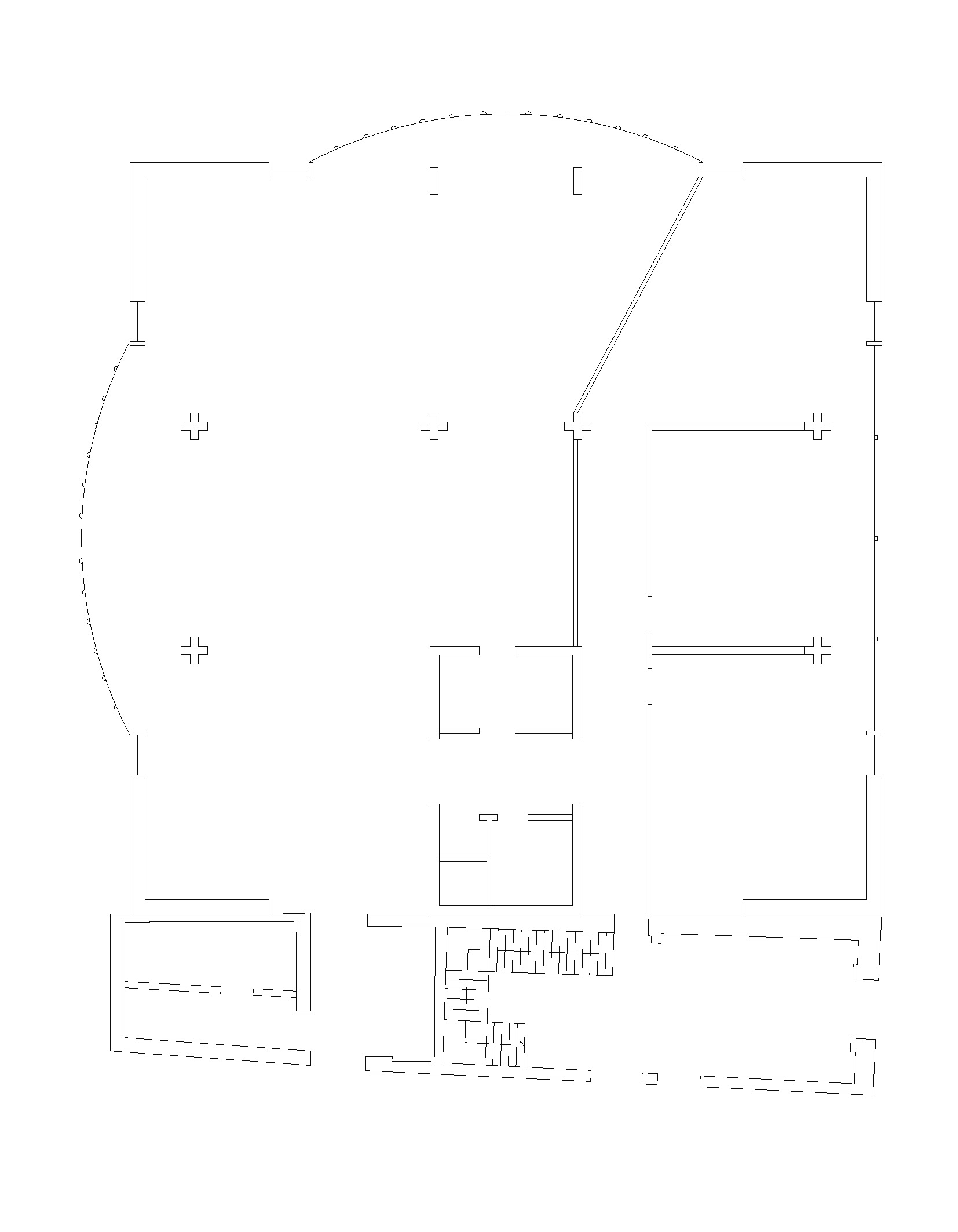

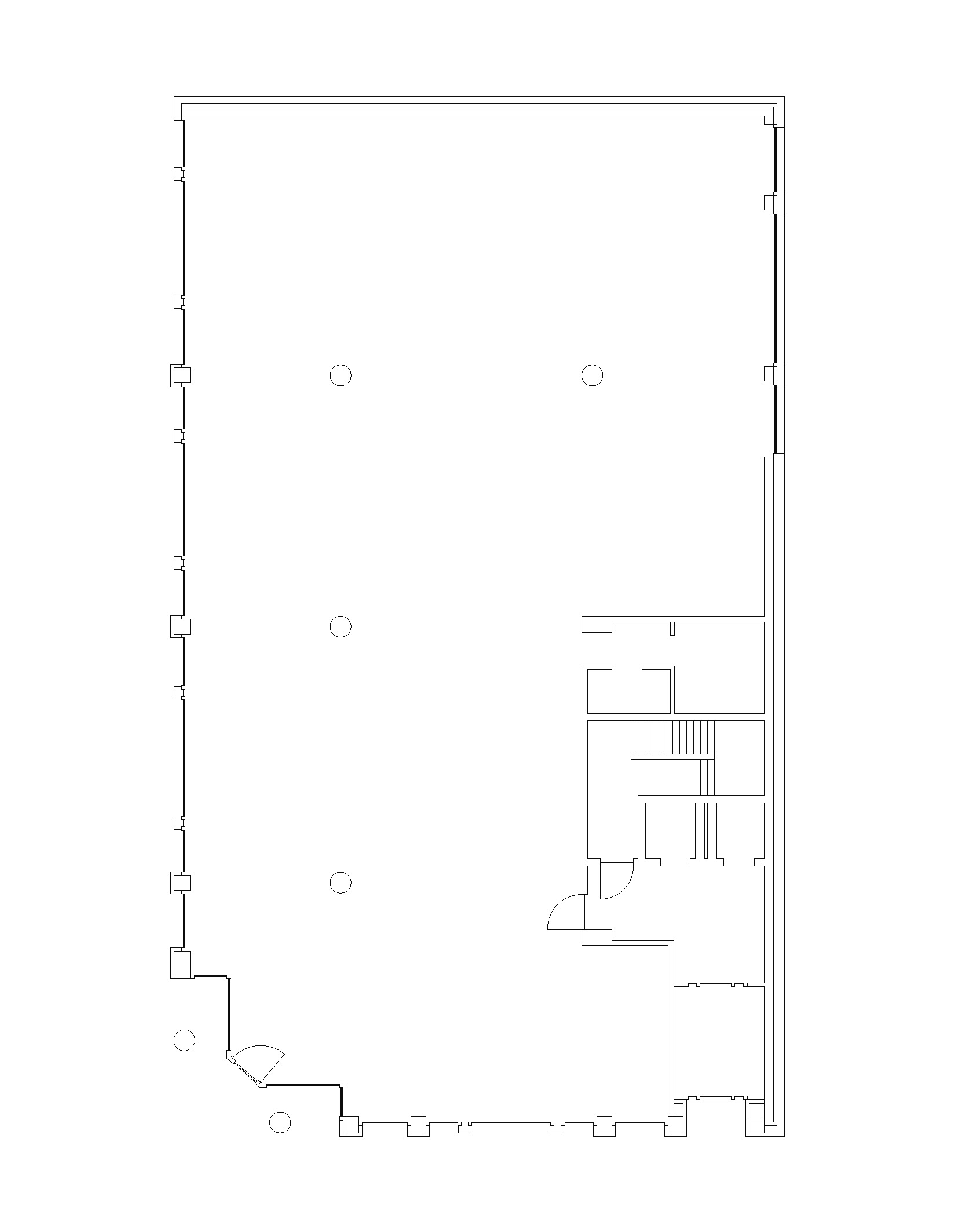

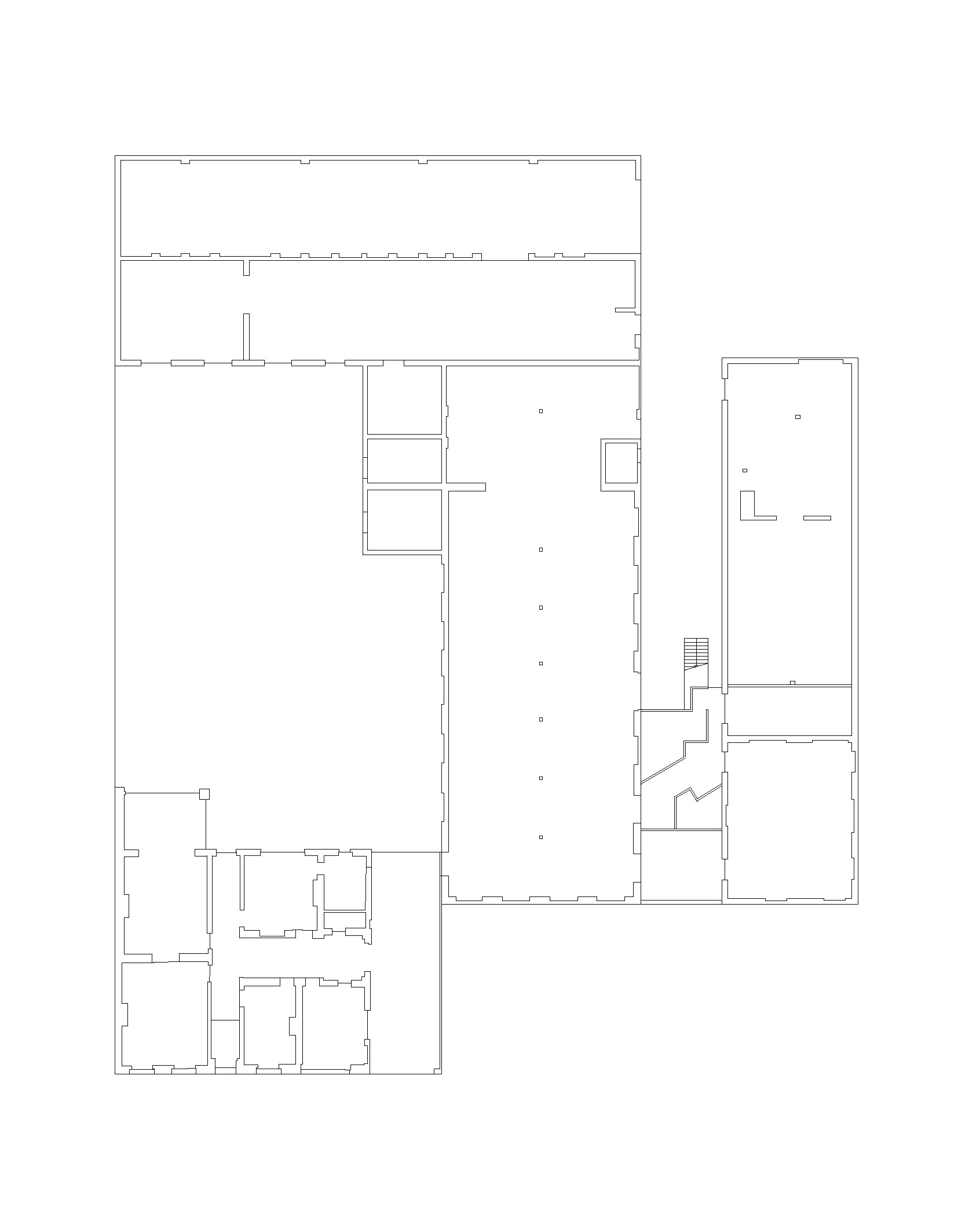

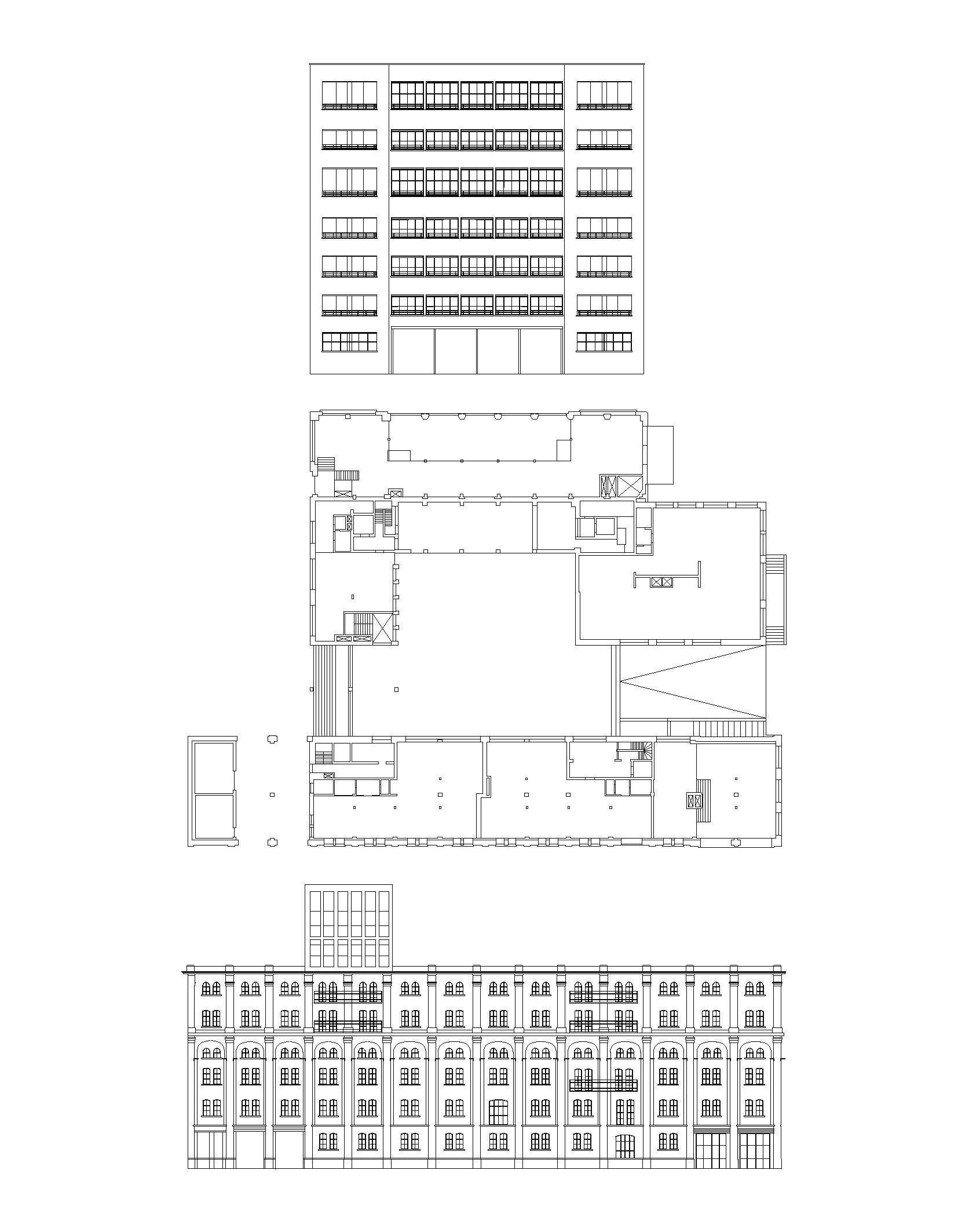

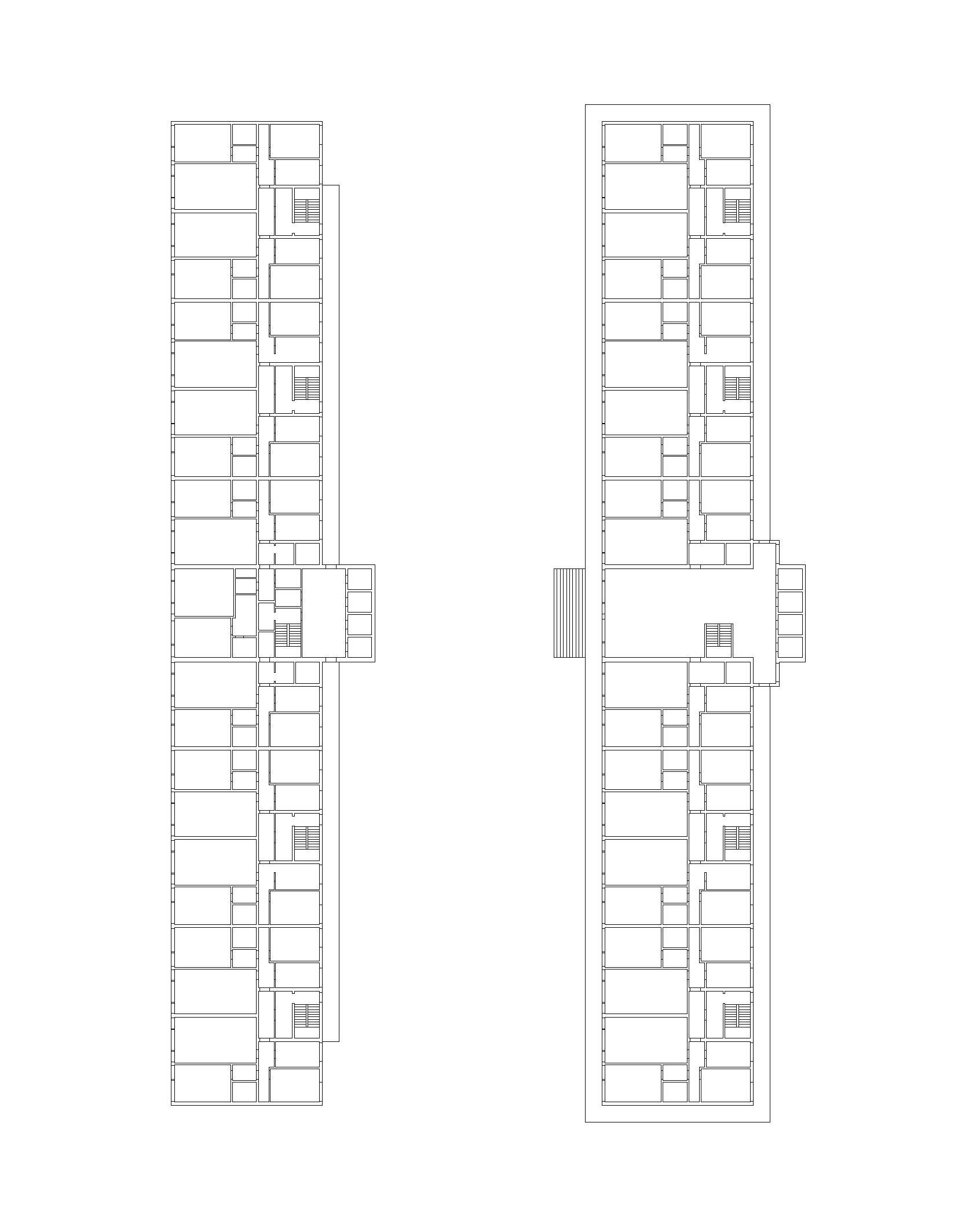

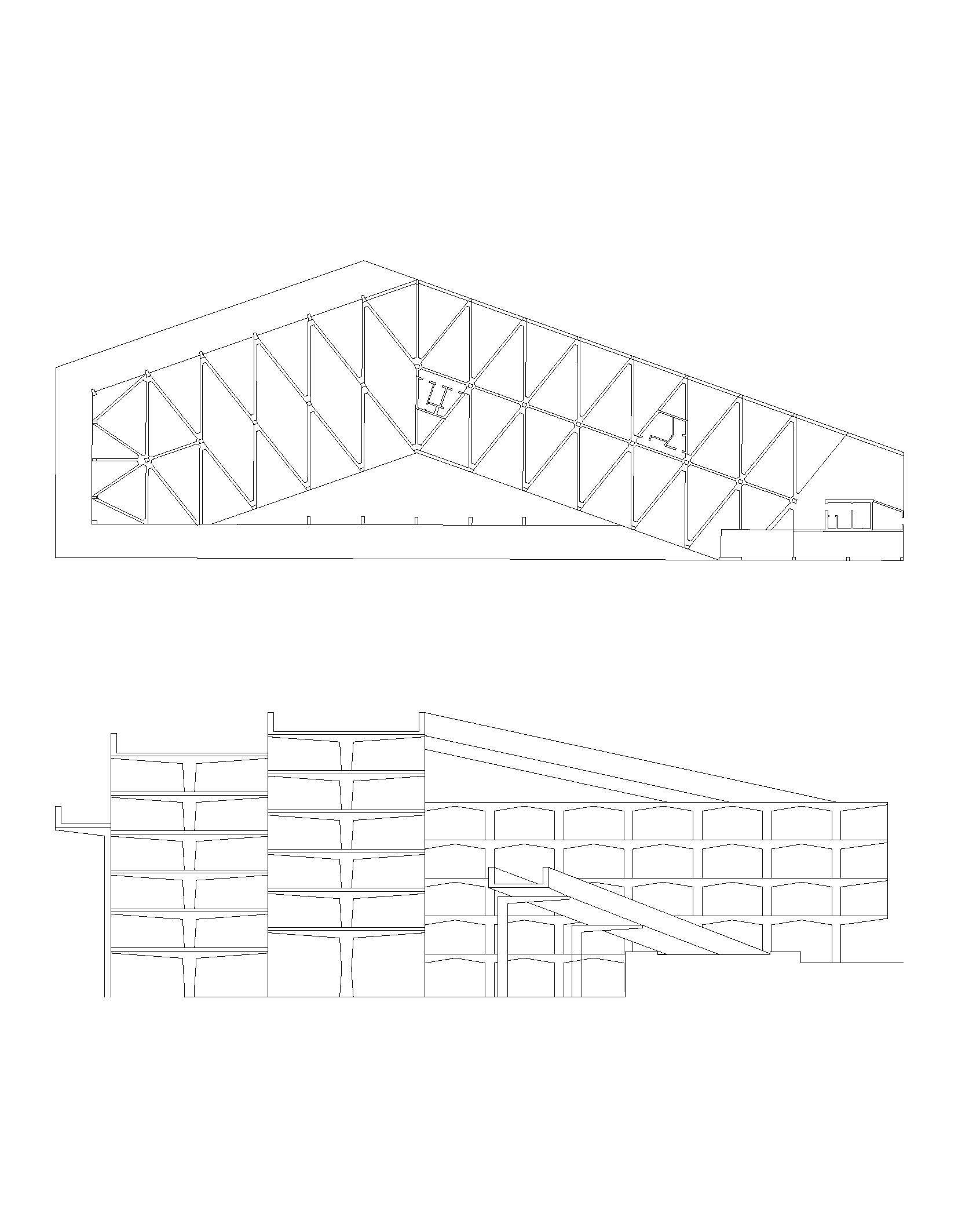

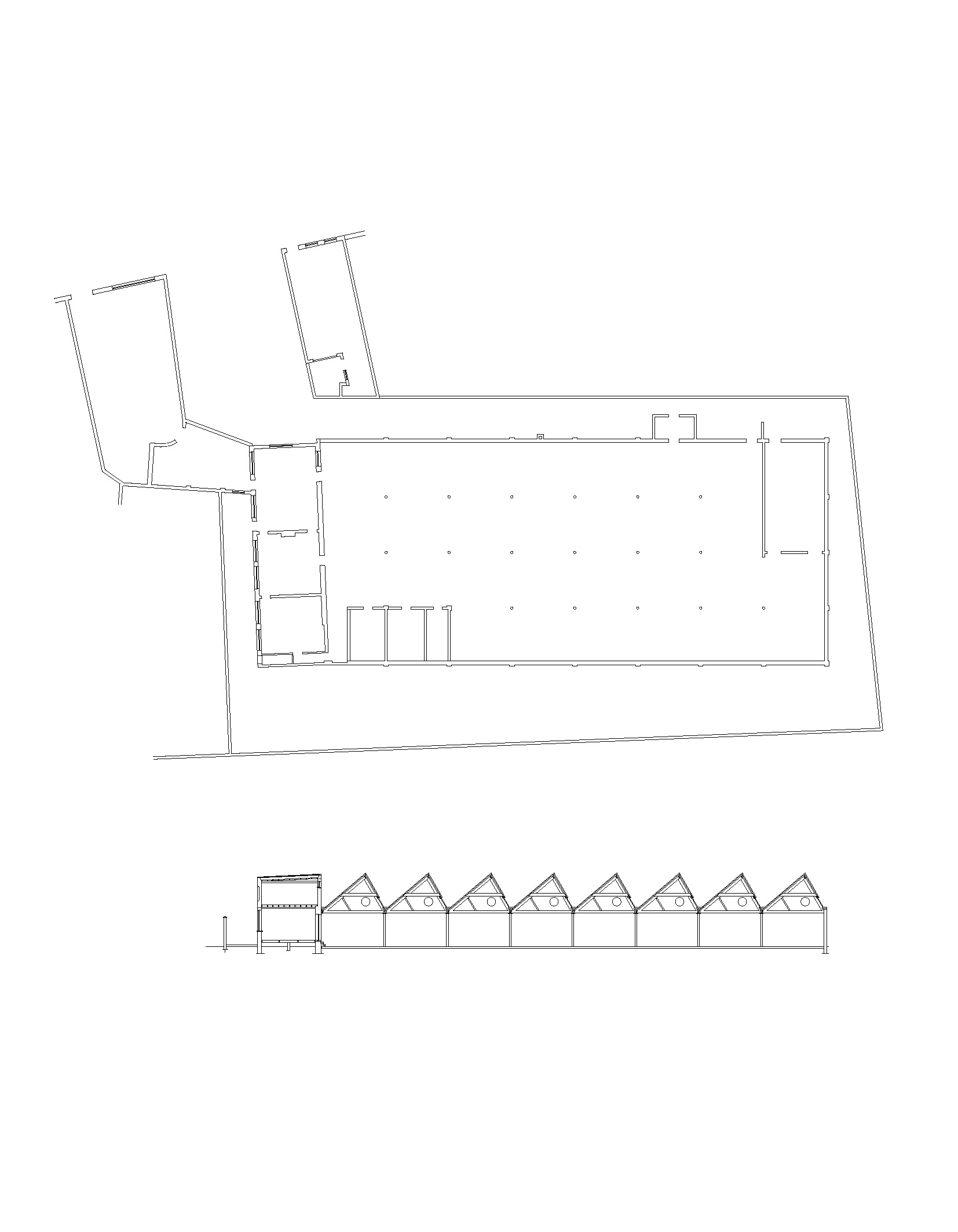

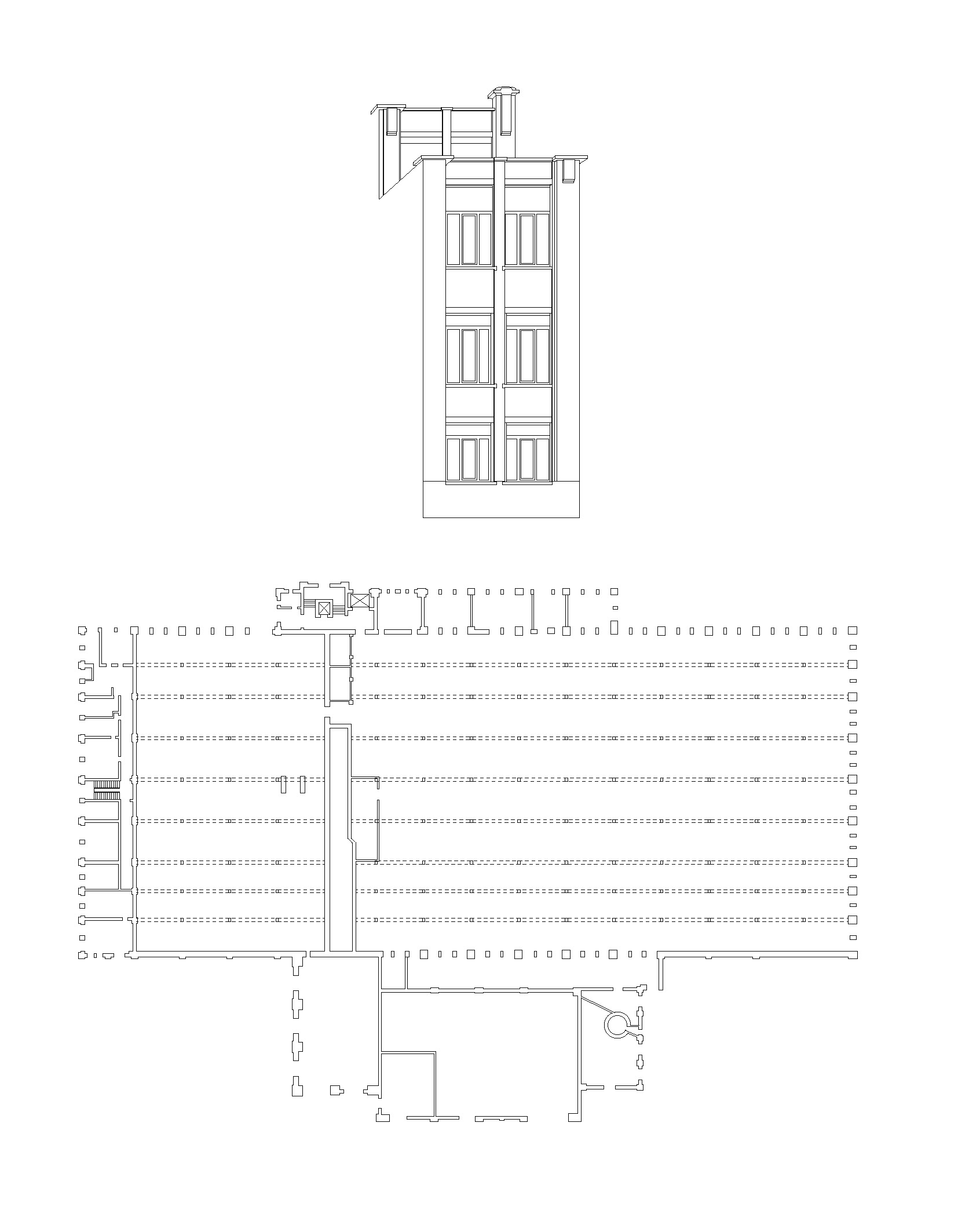

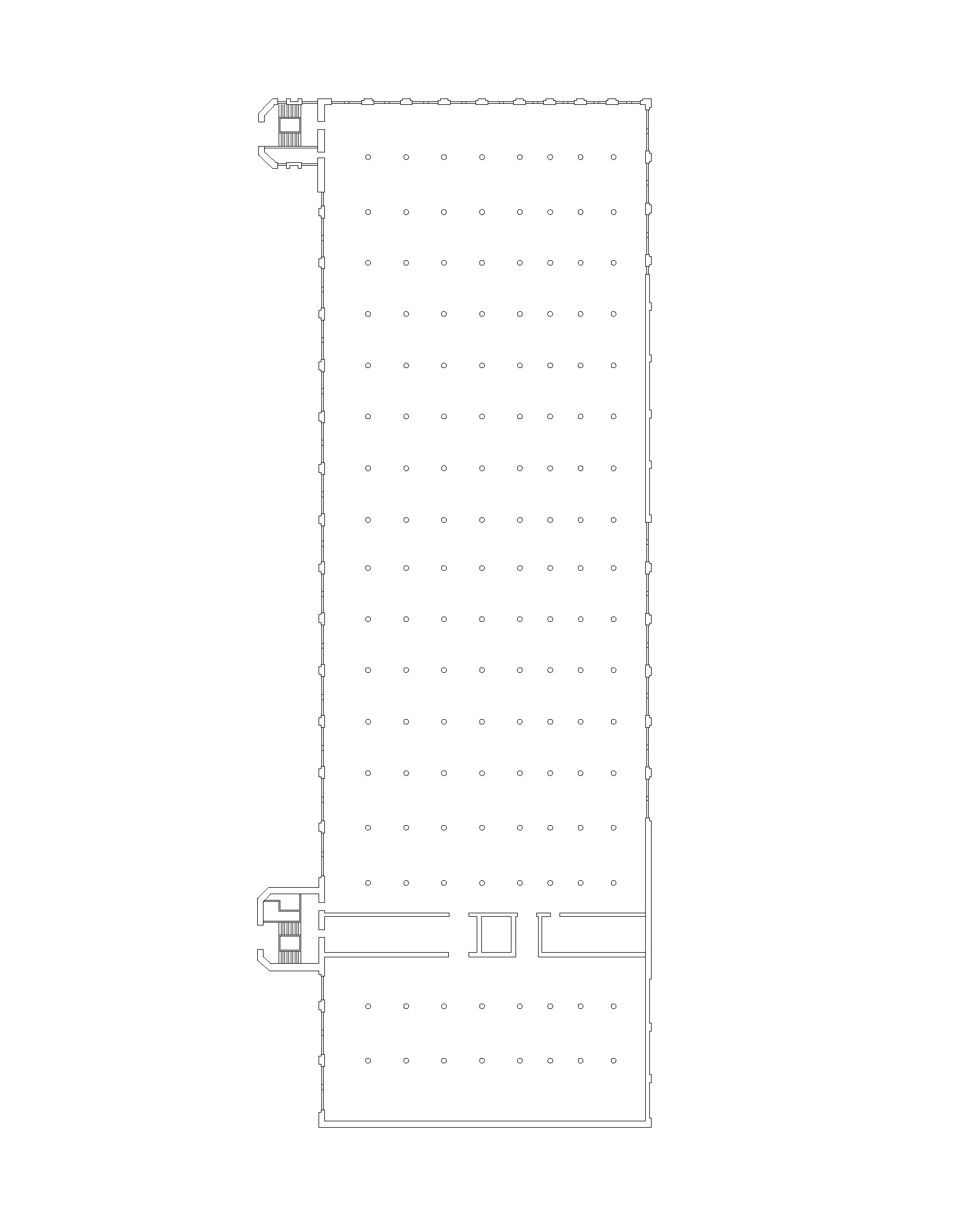

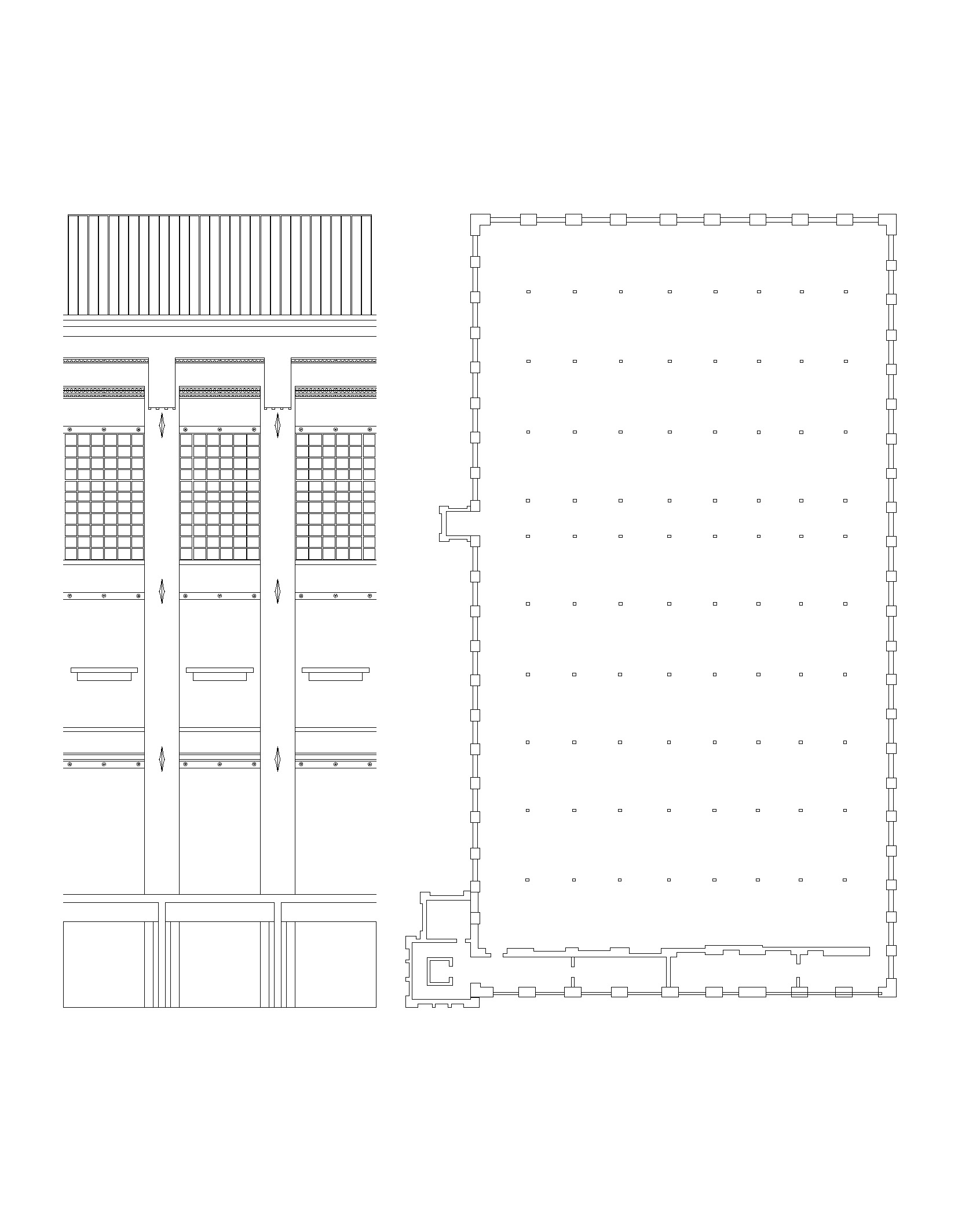

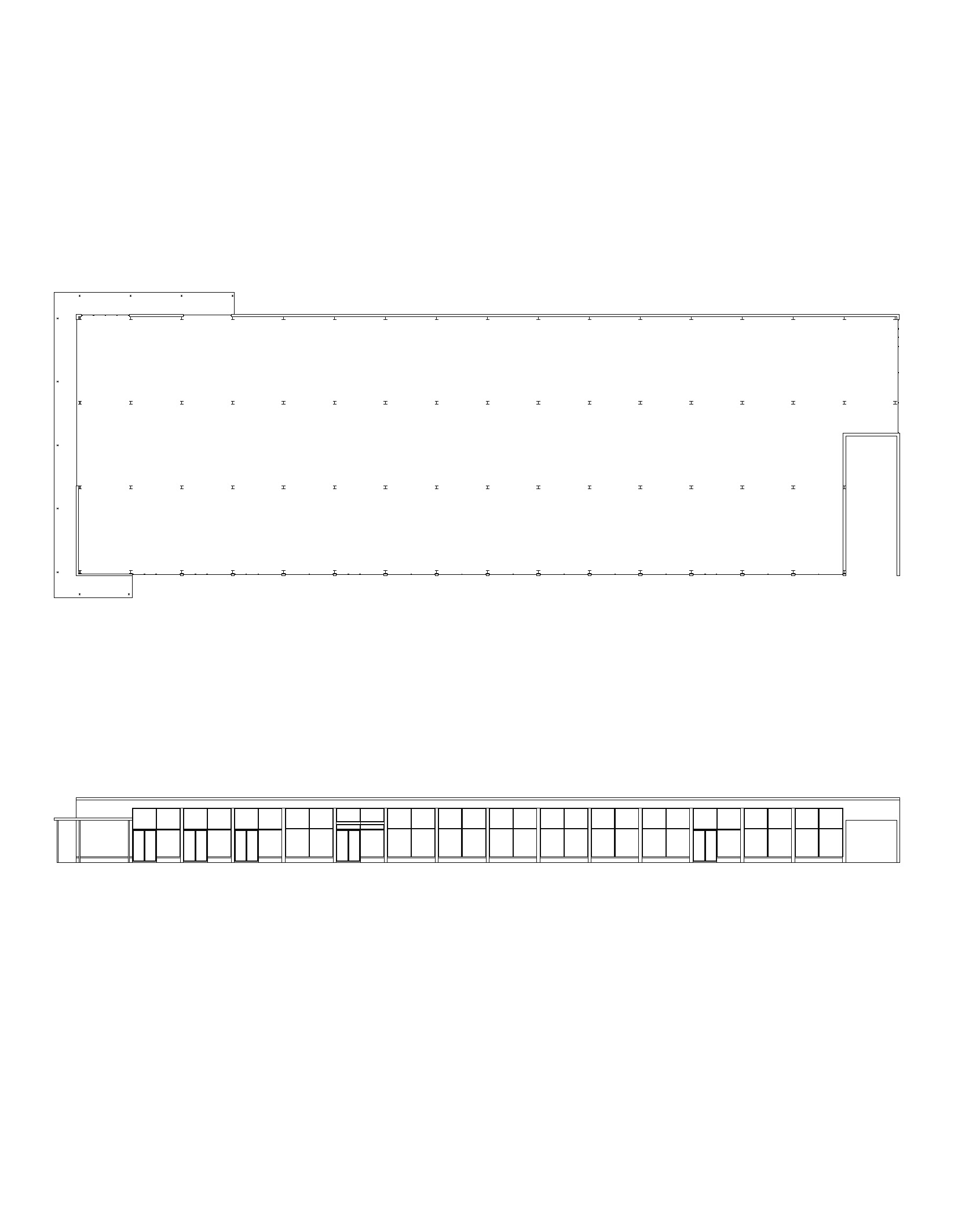

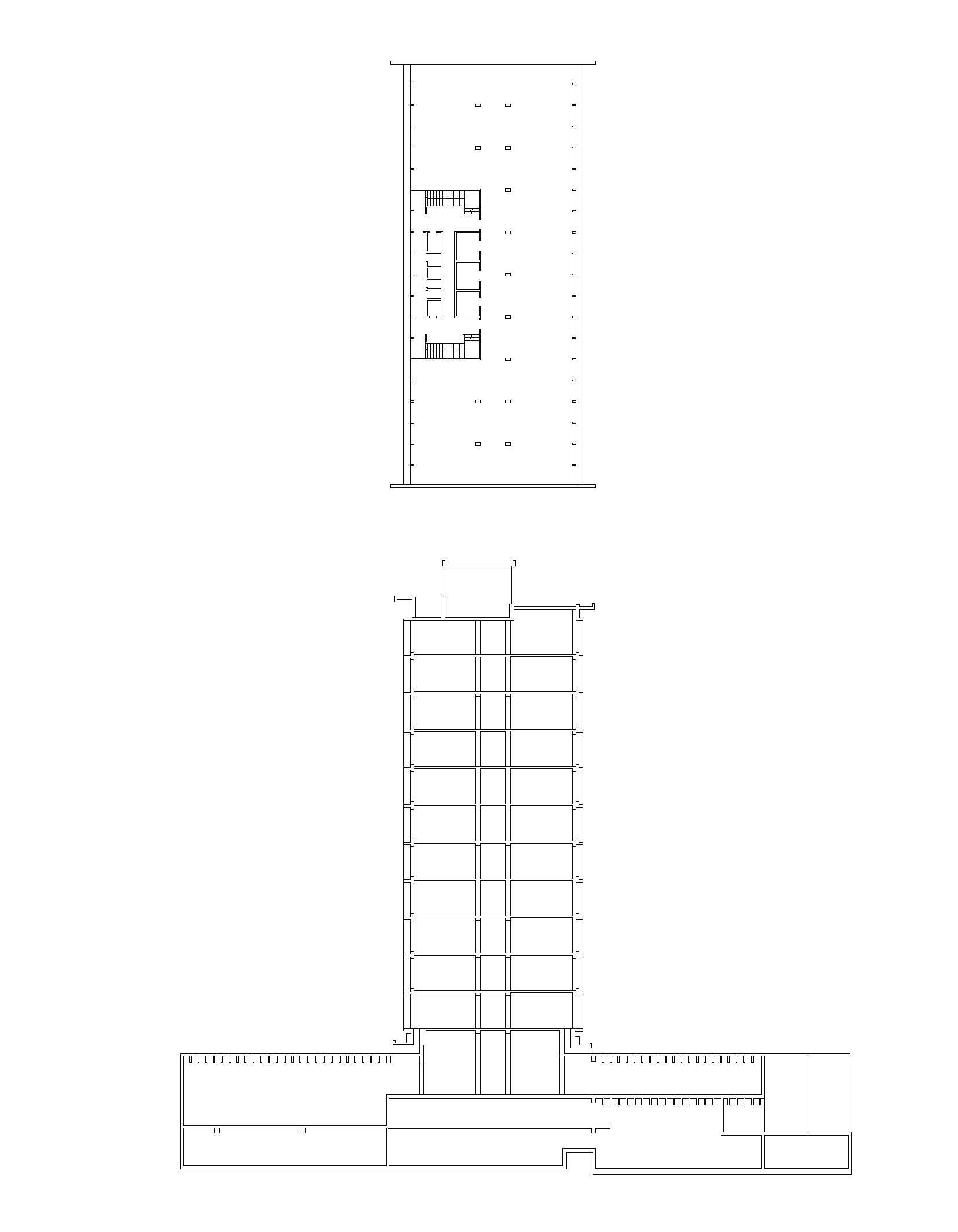

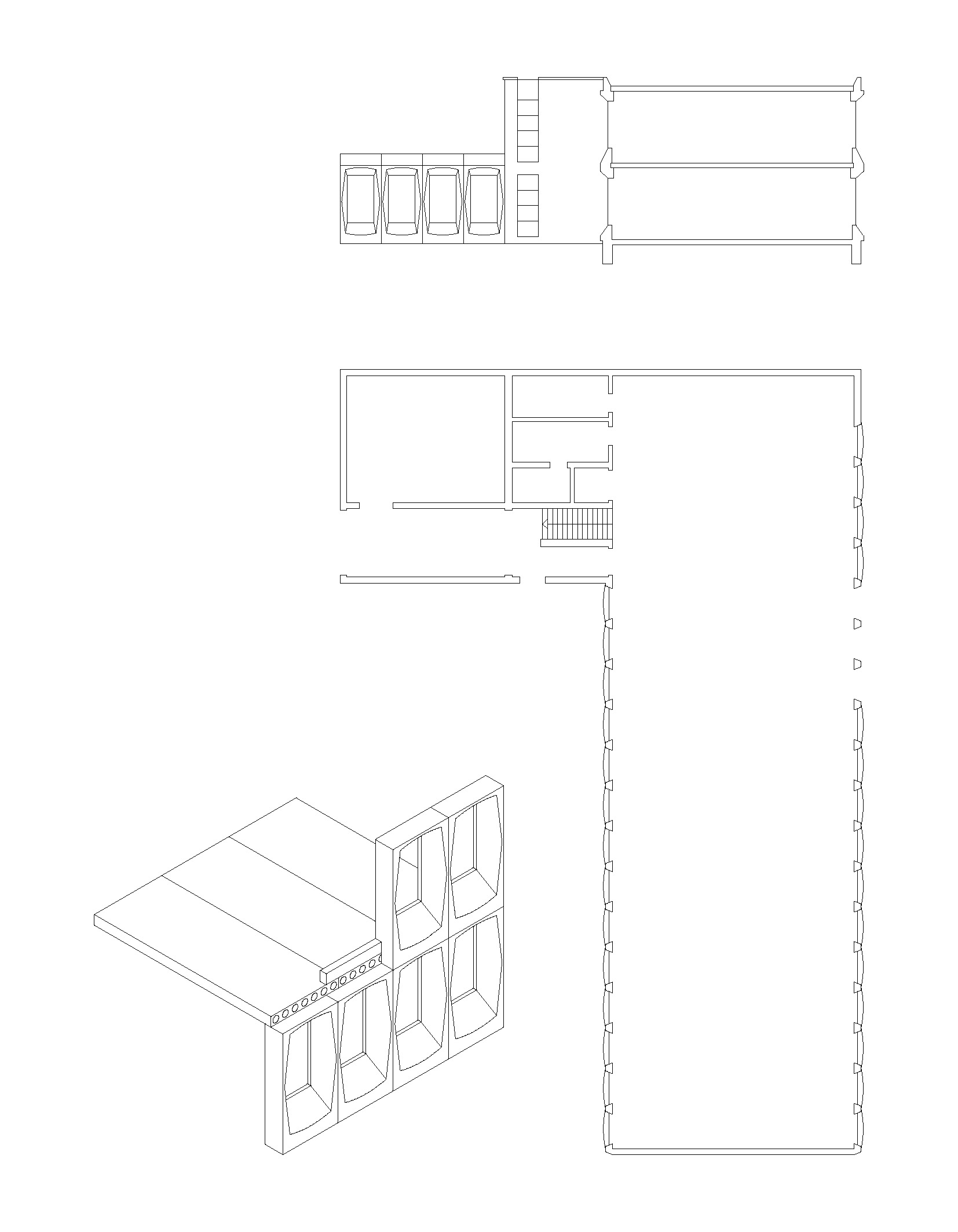

BUILDING BLOCK

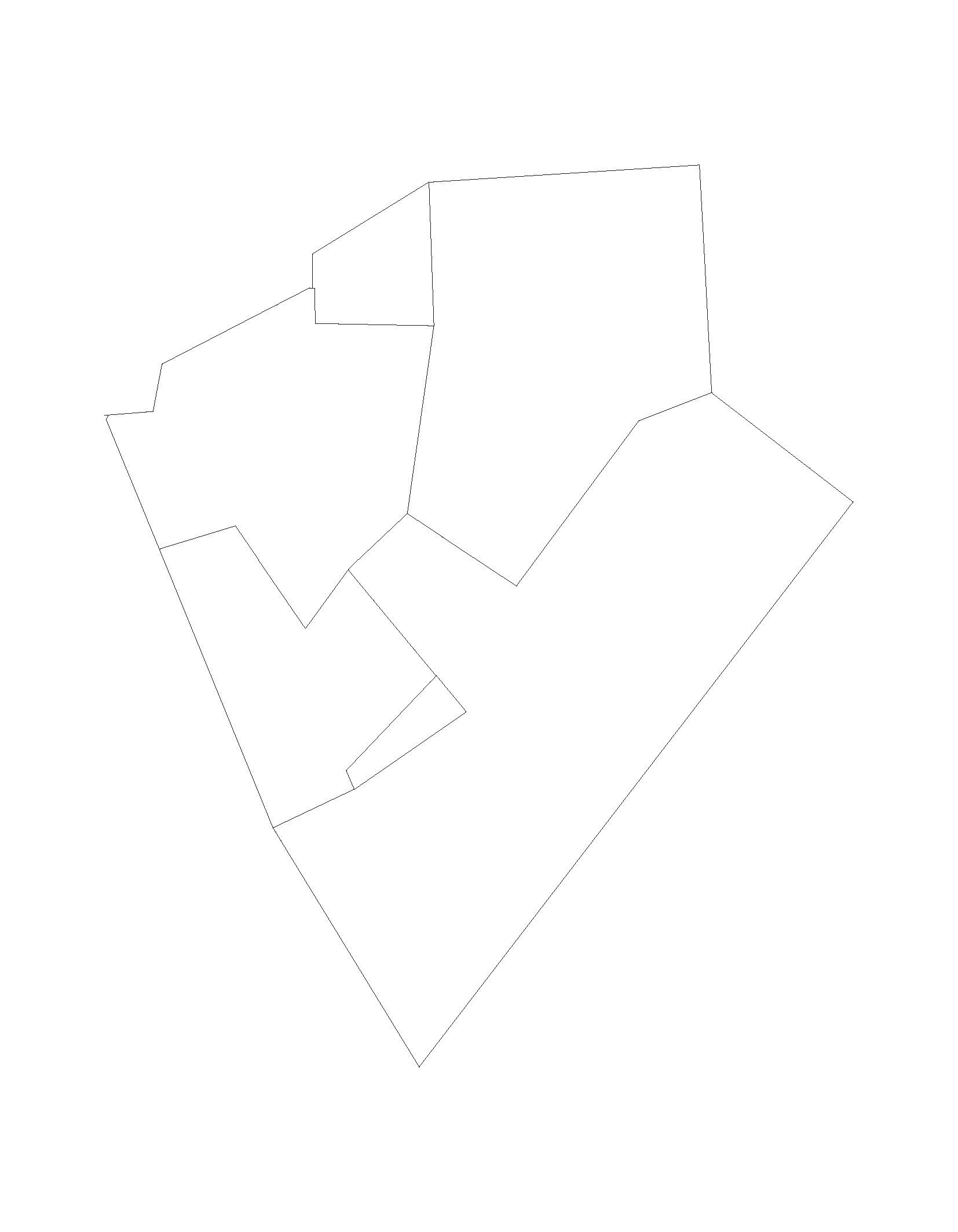

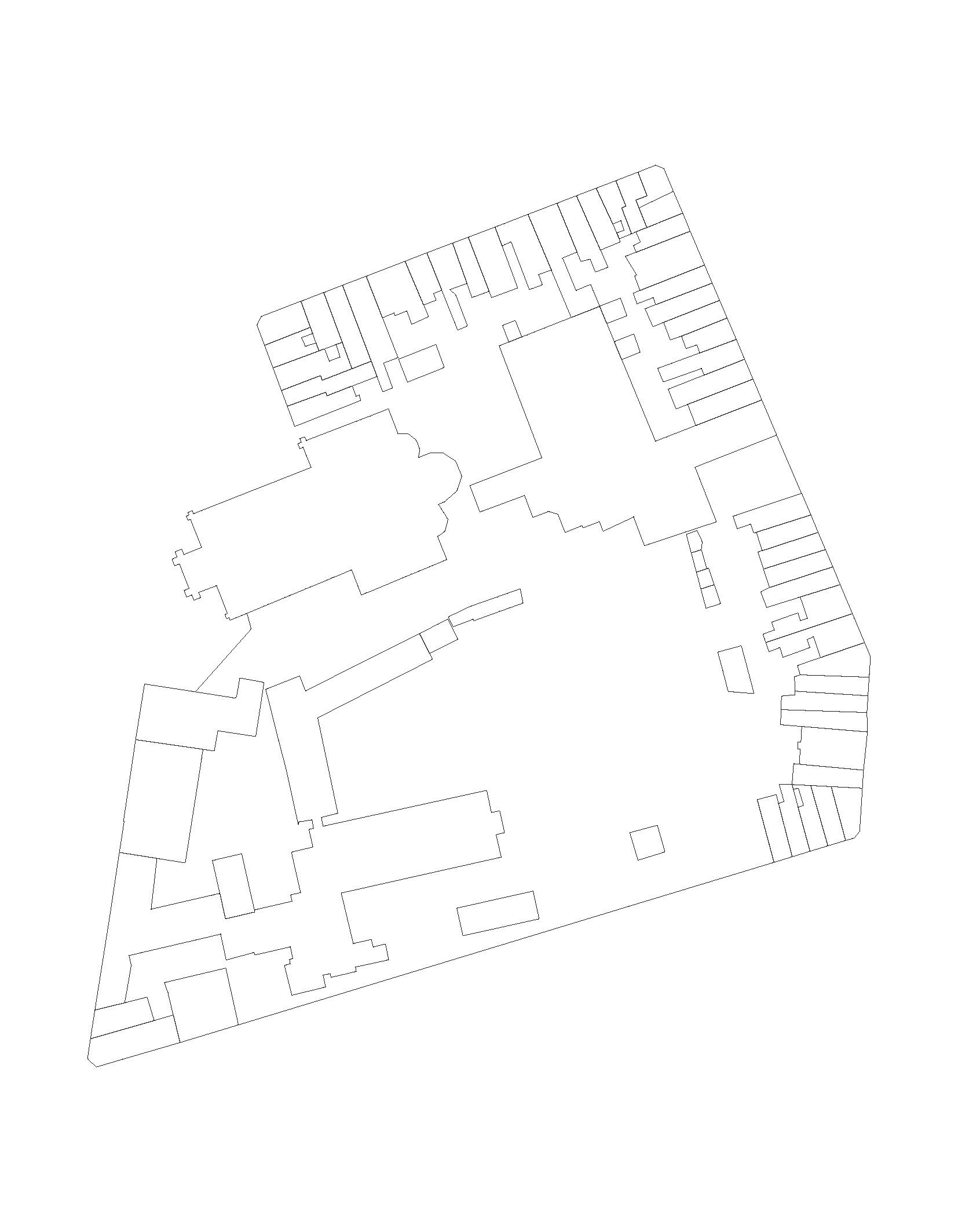

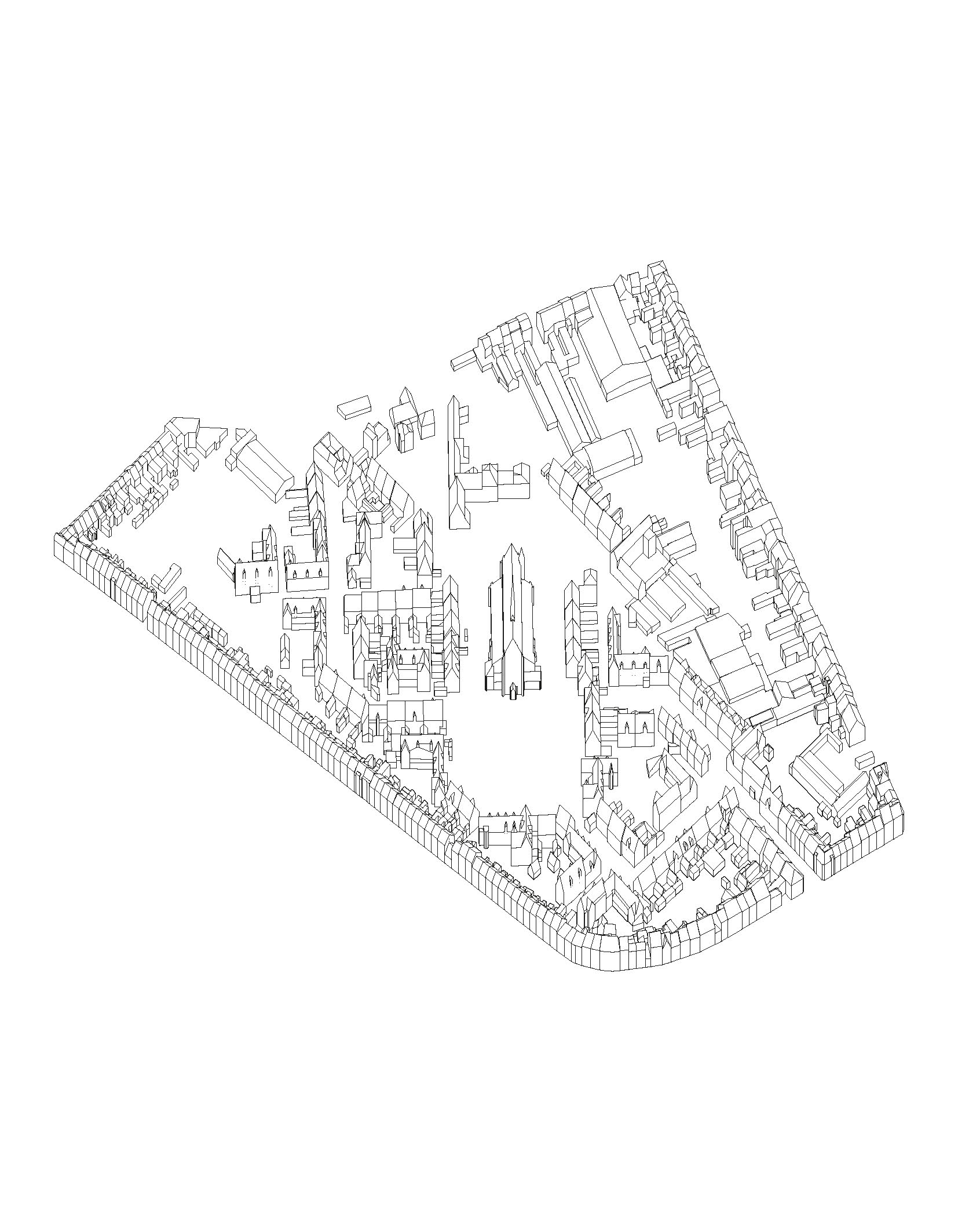

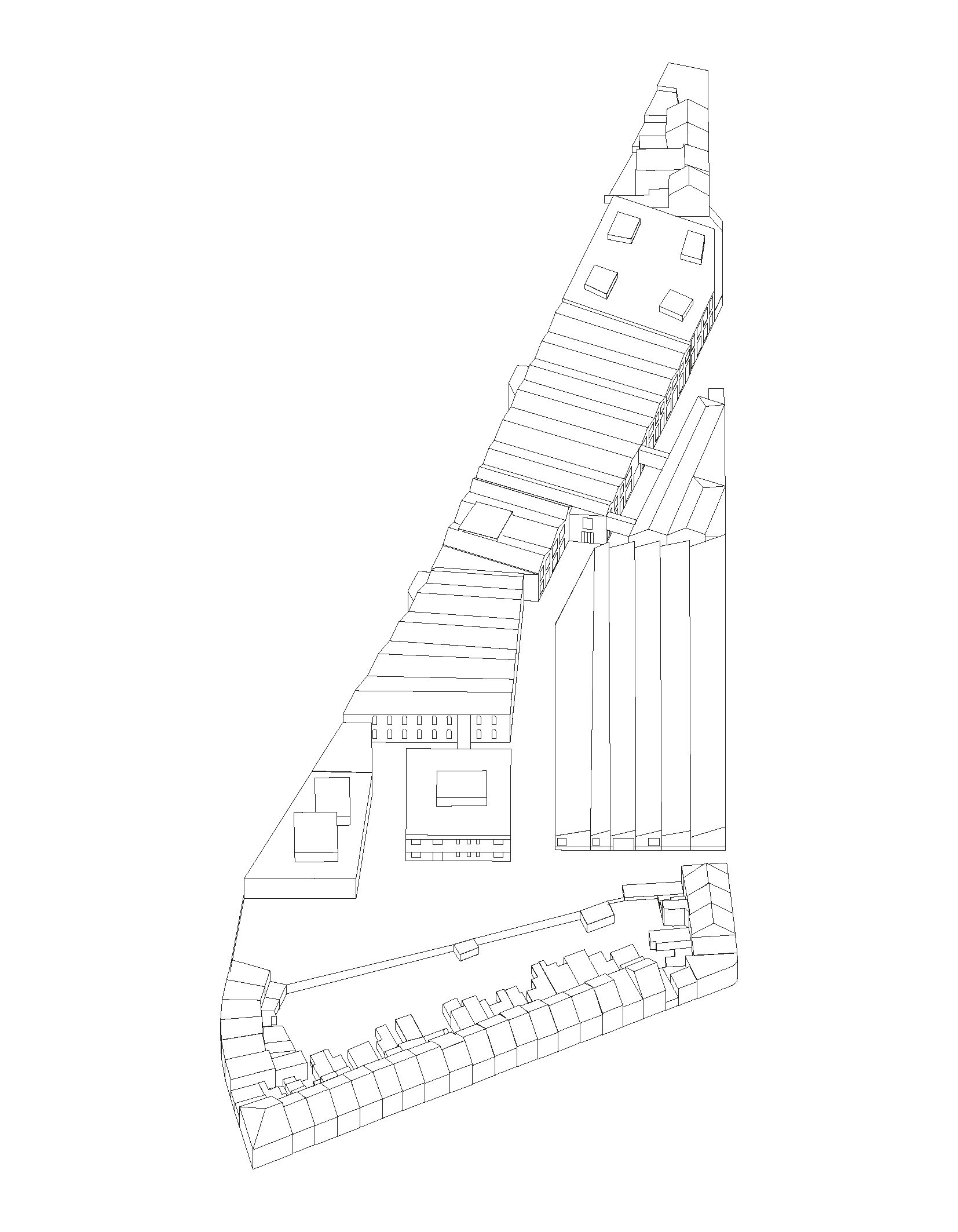

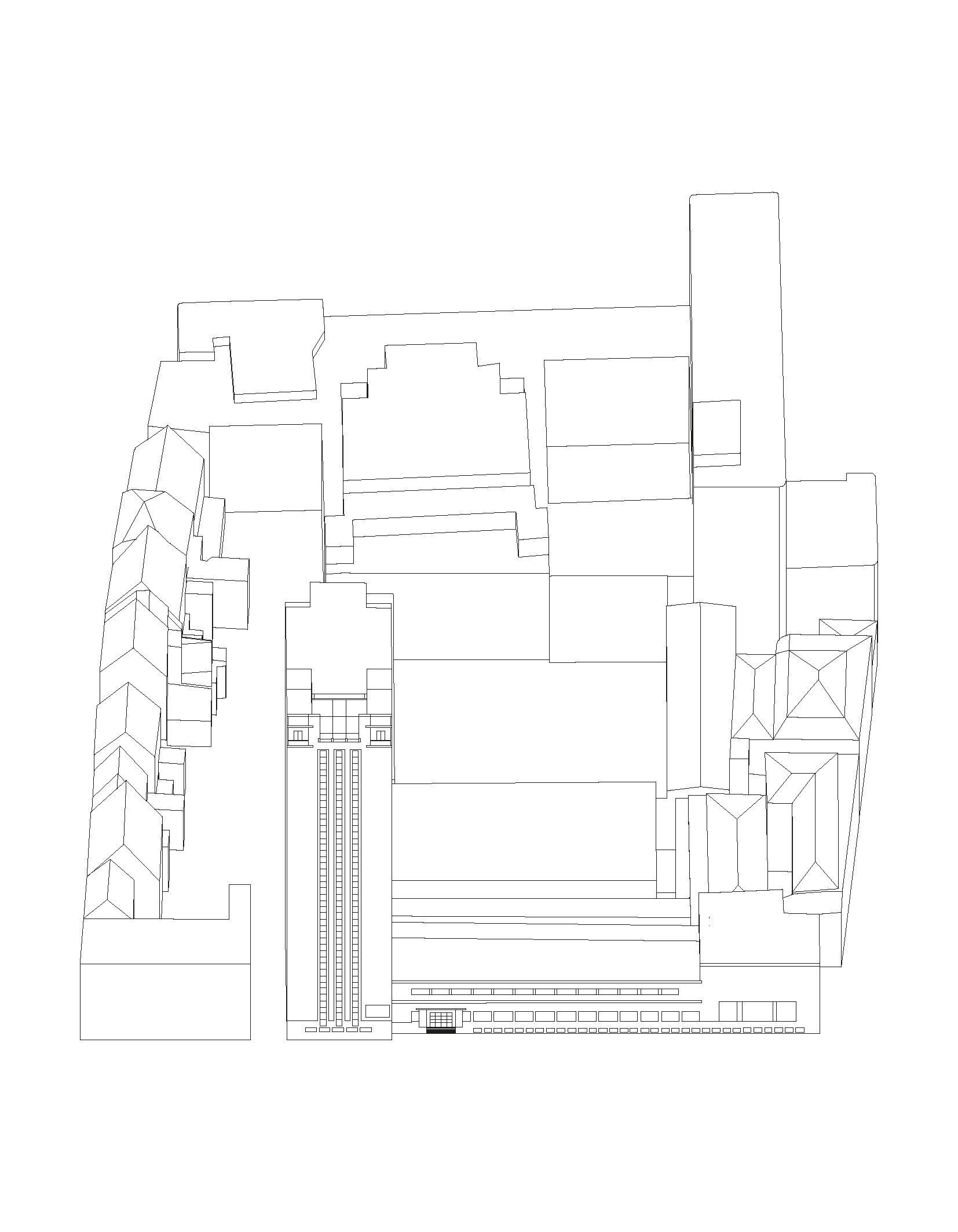

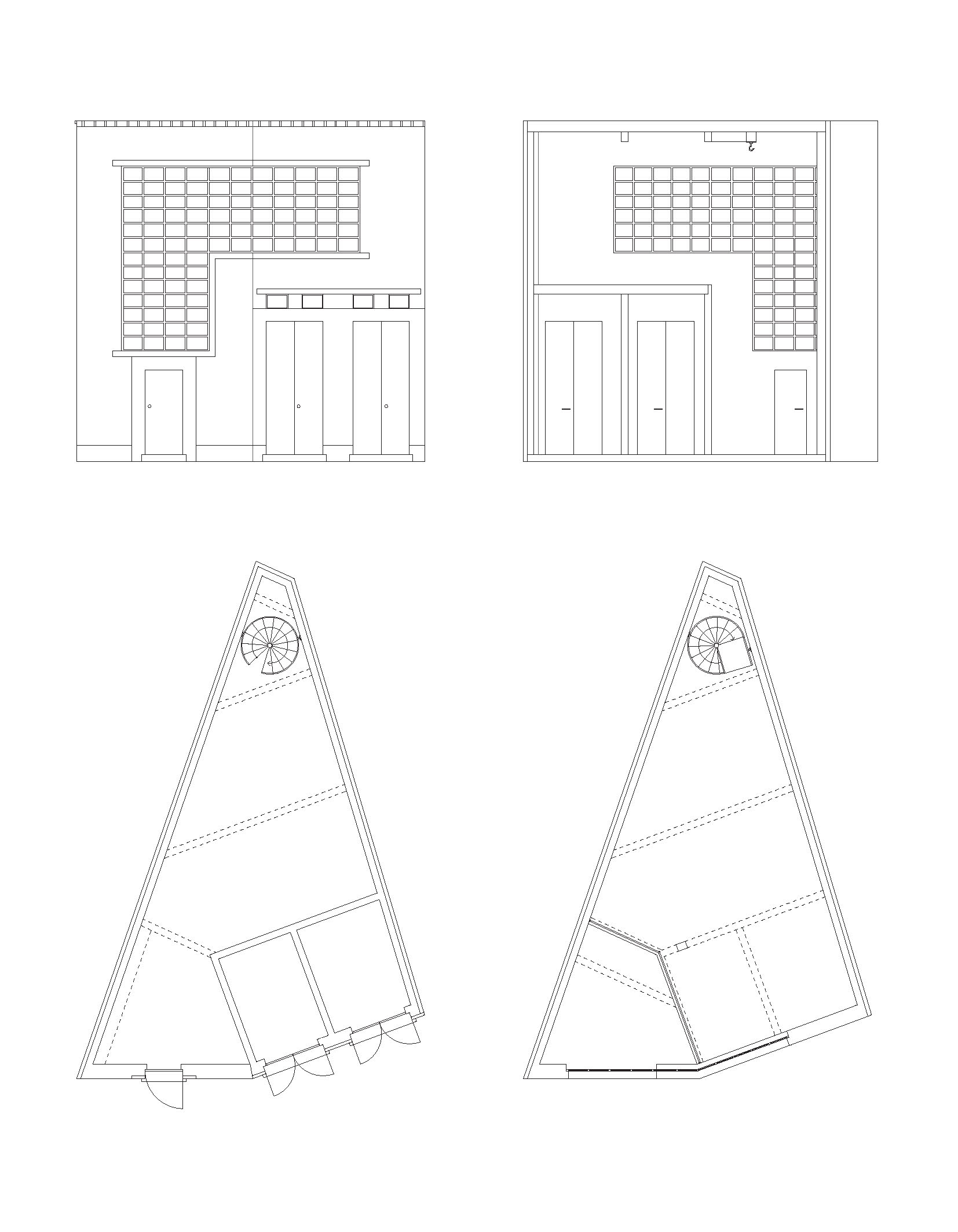

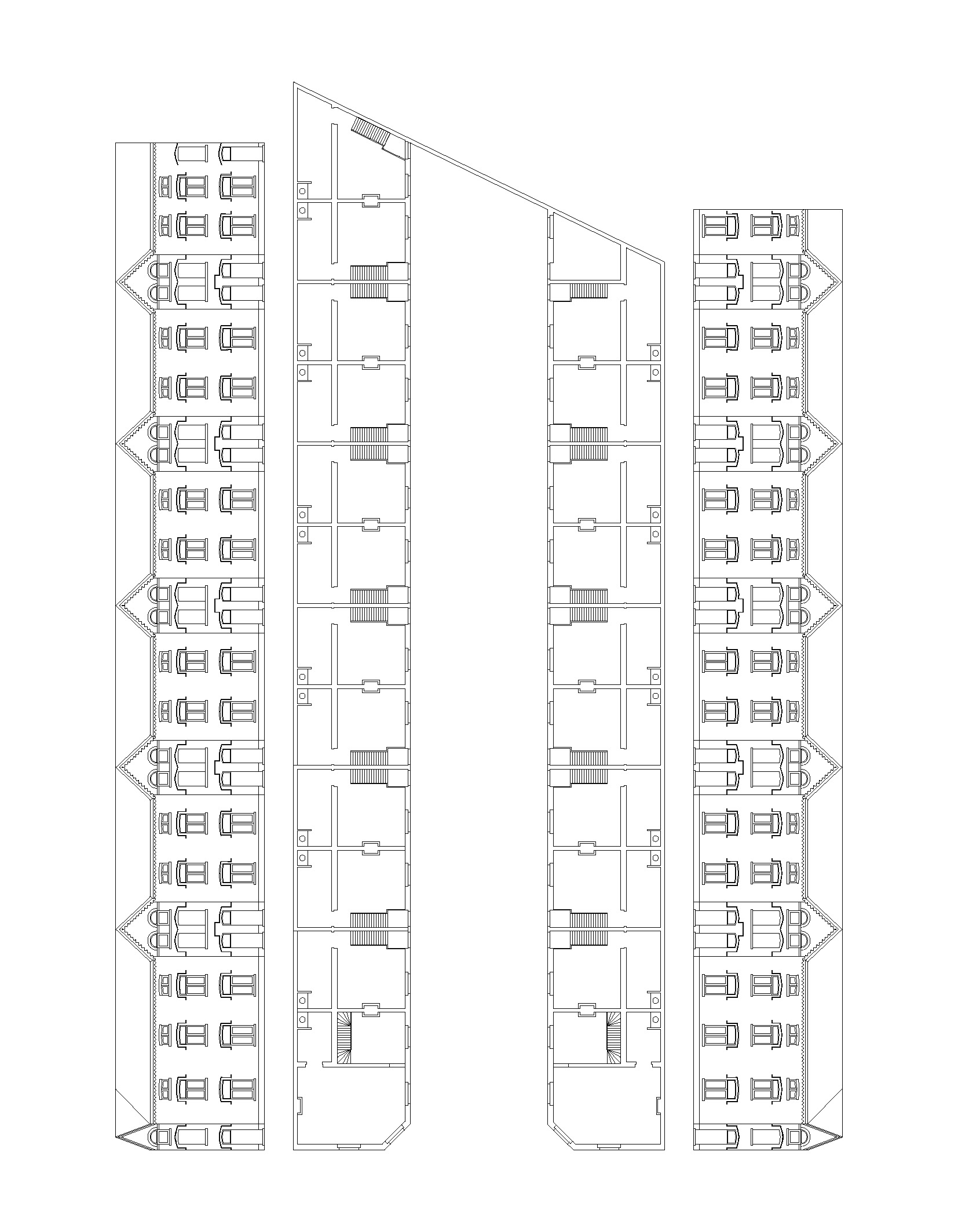

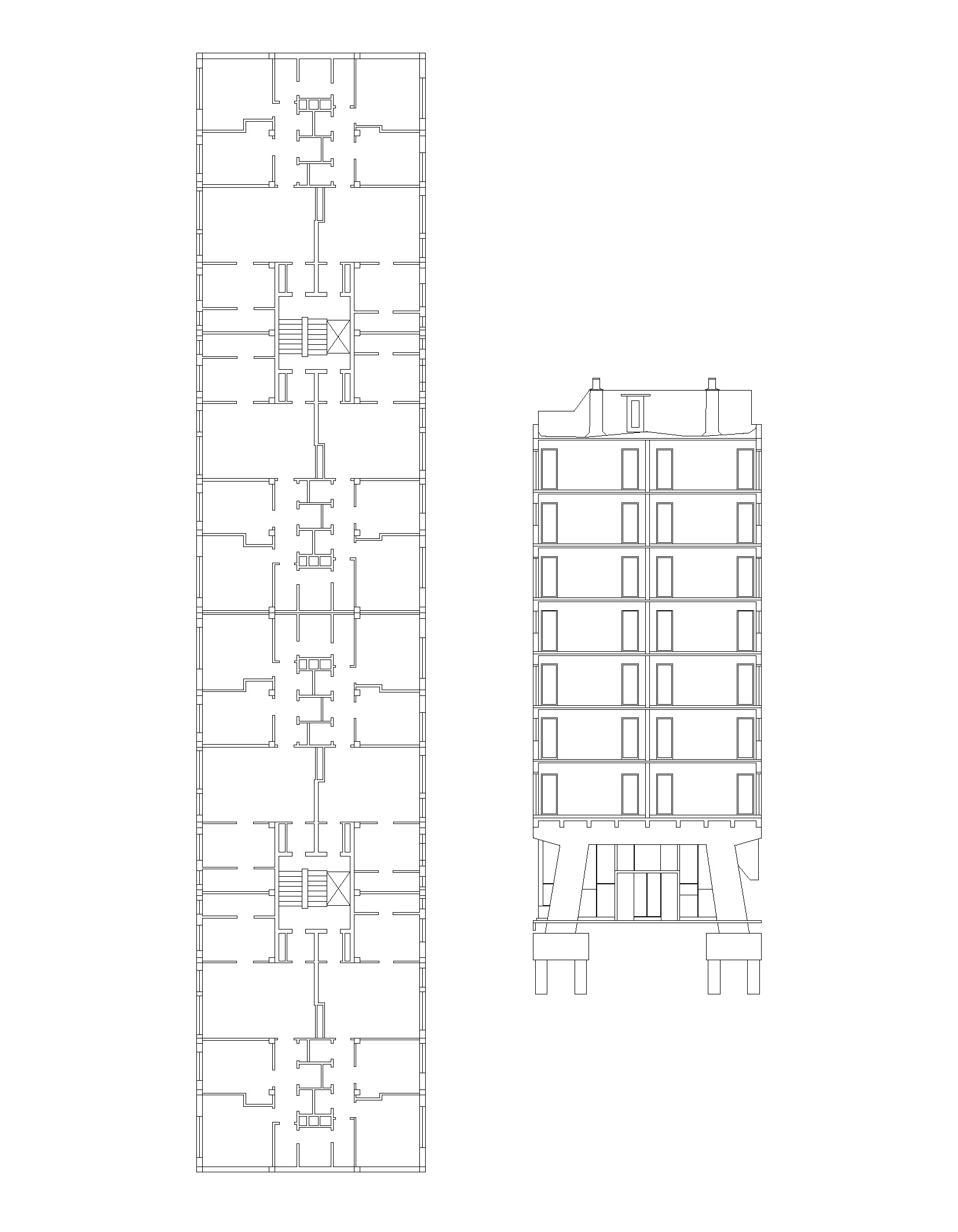

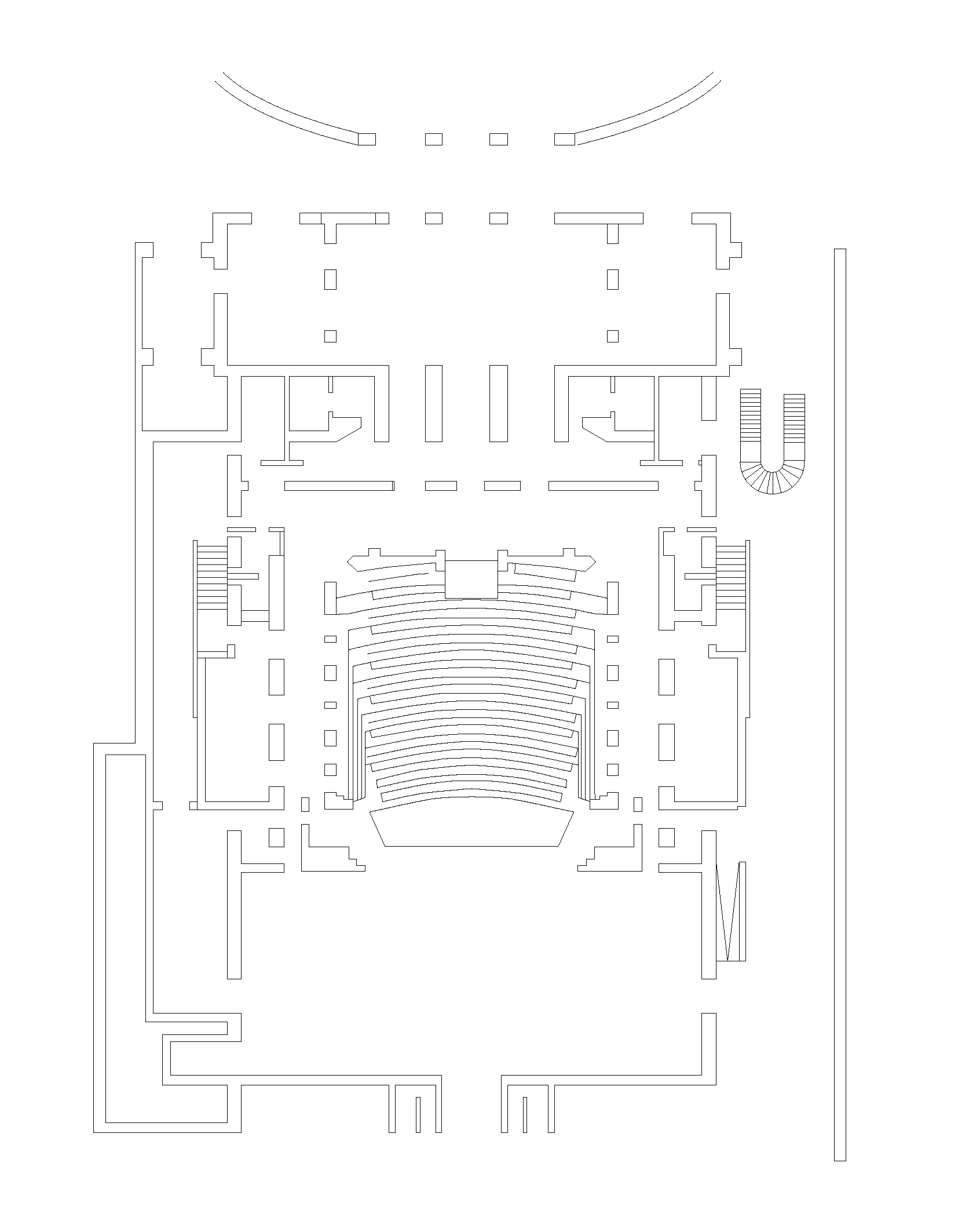

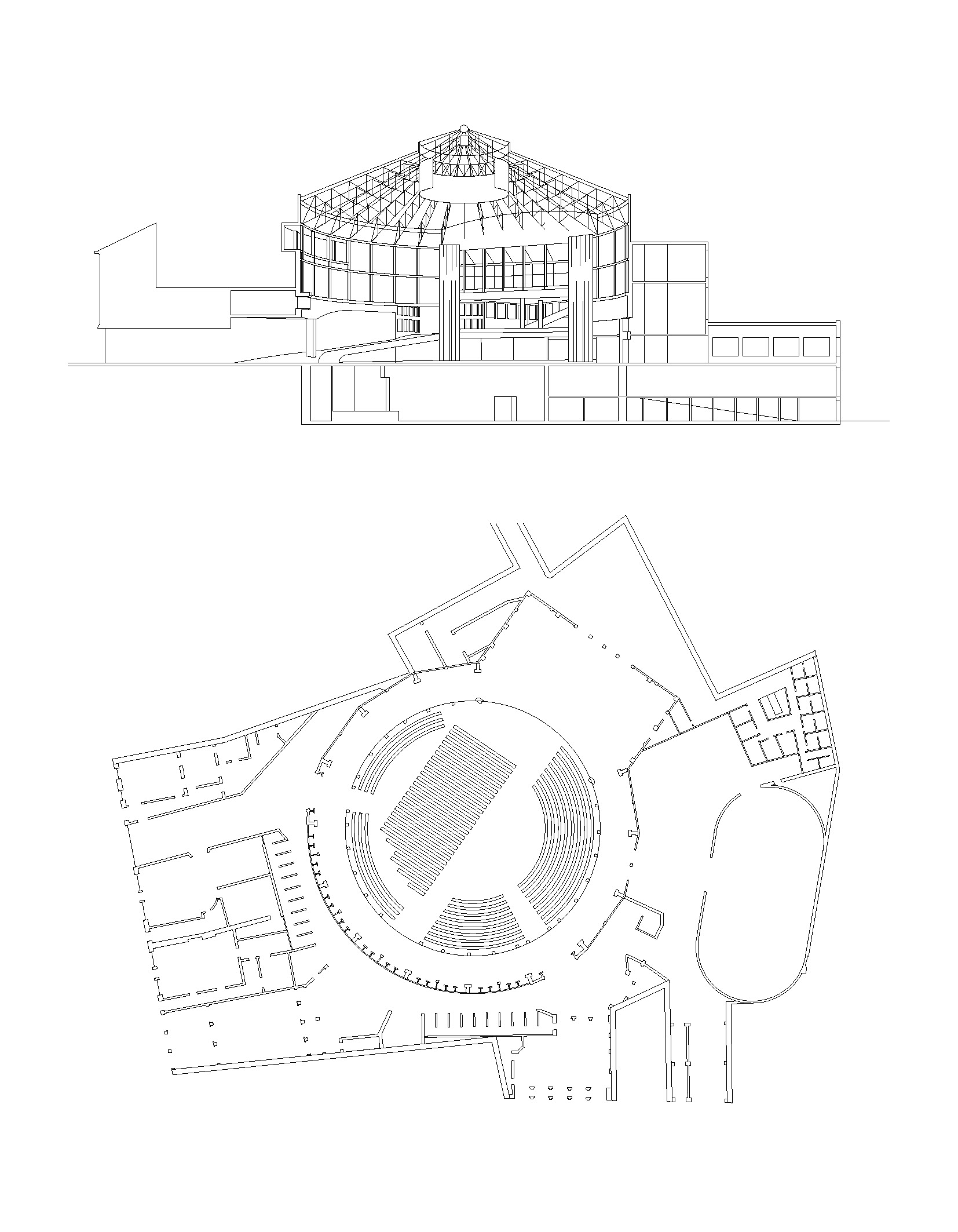

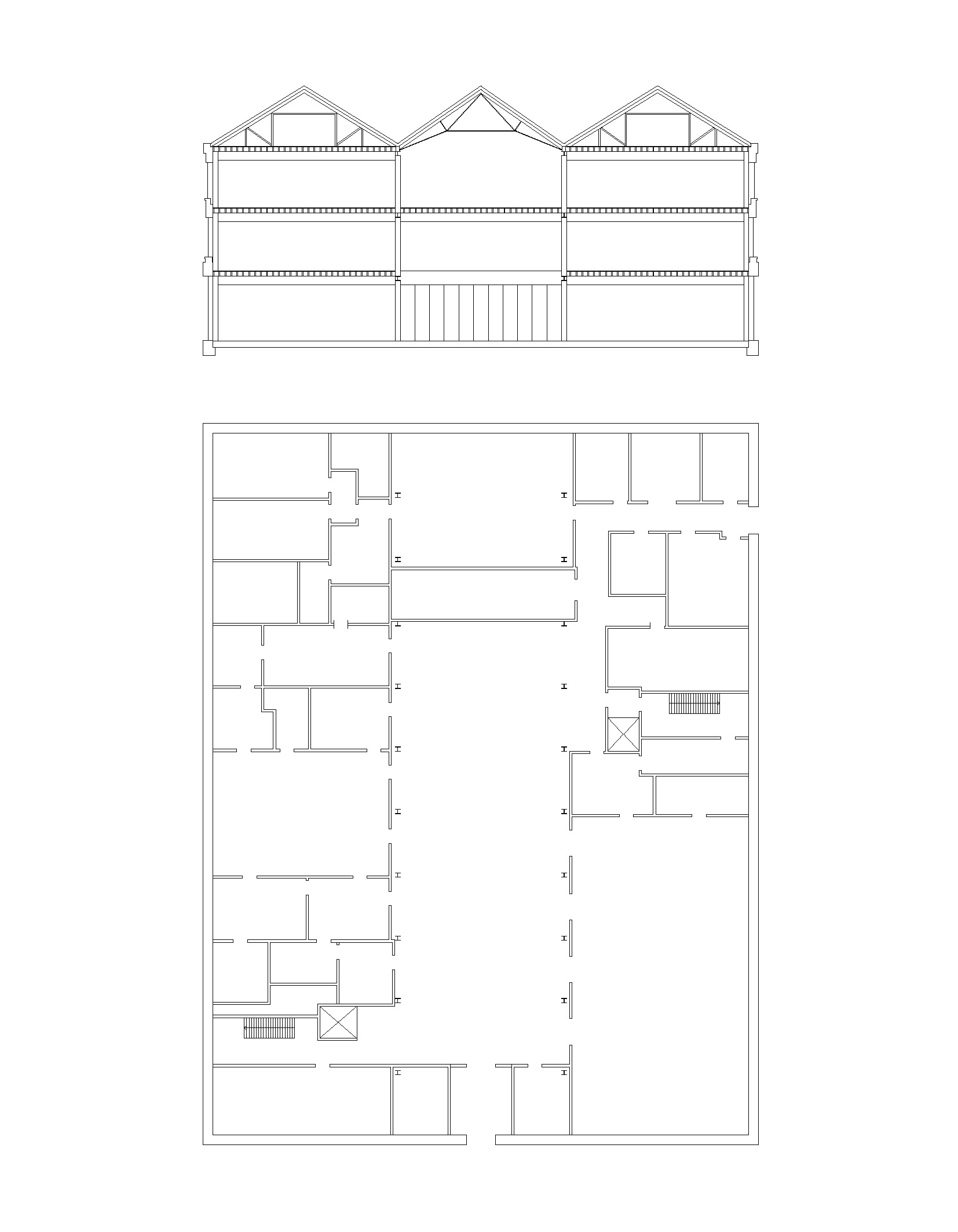

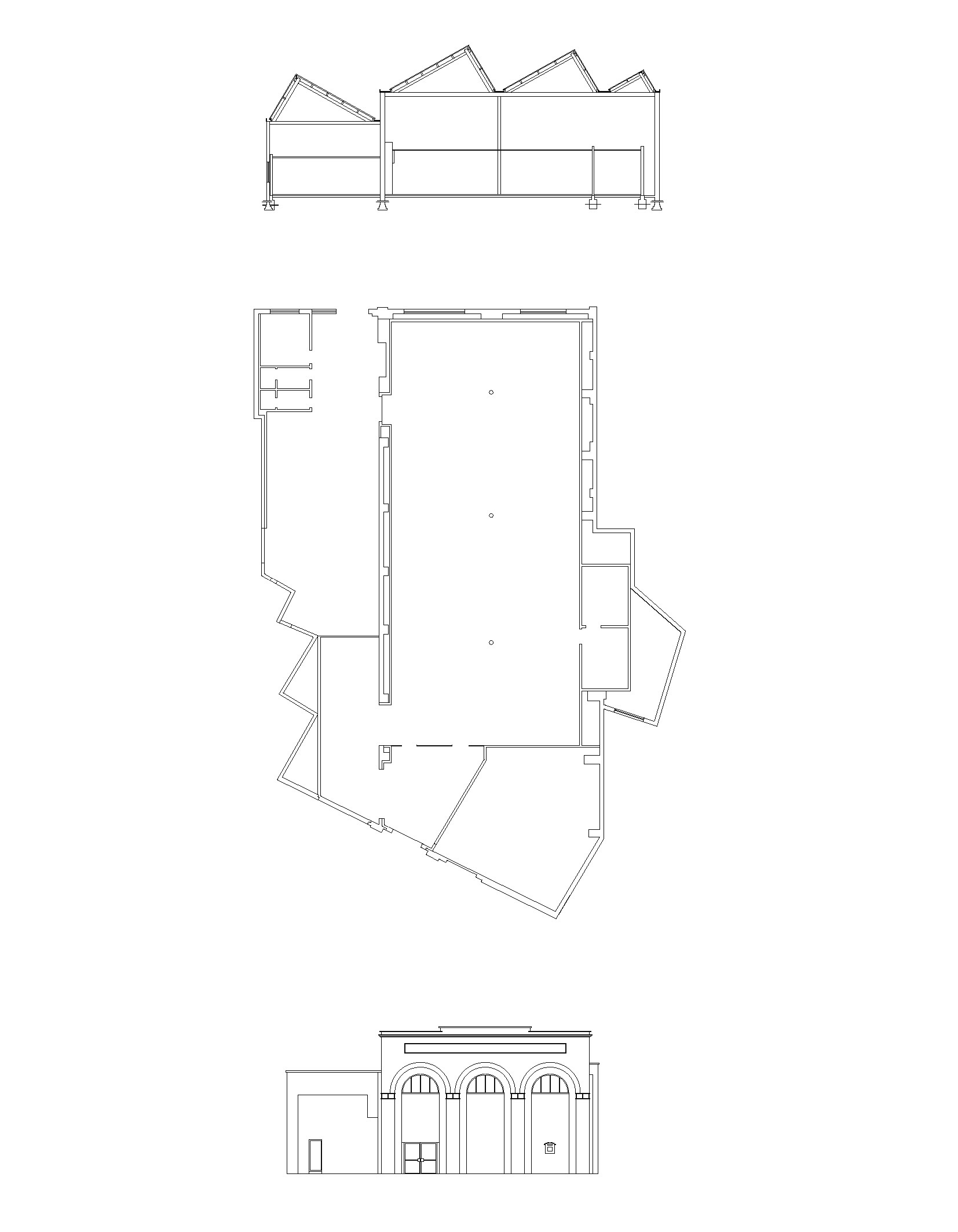

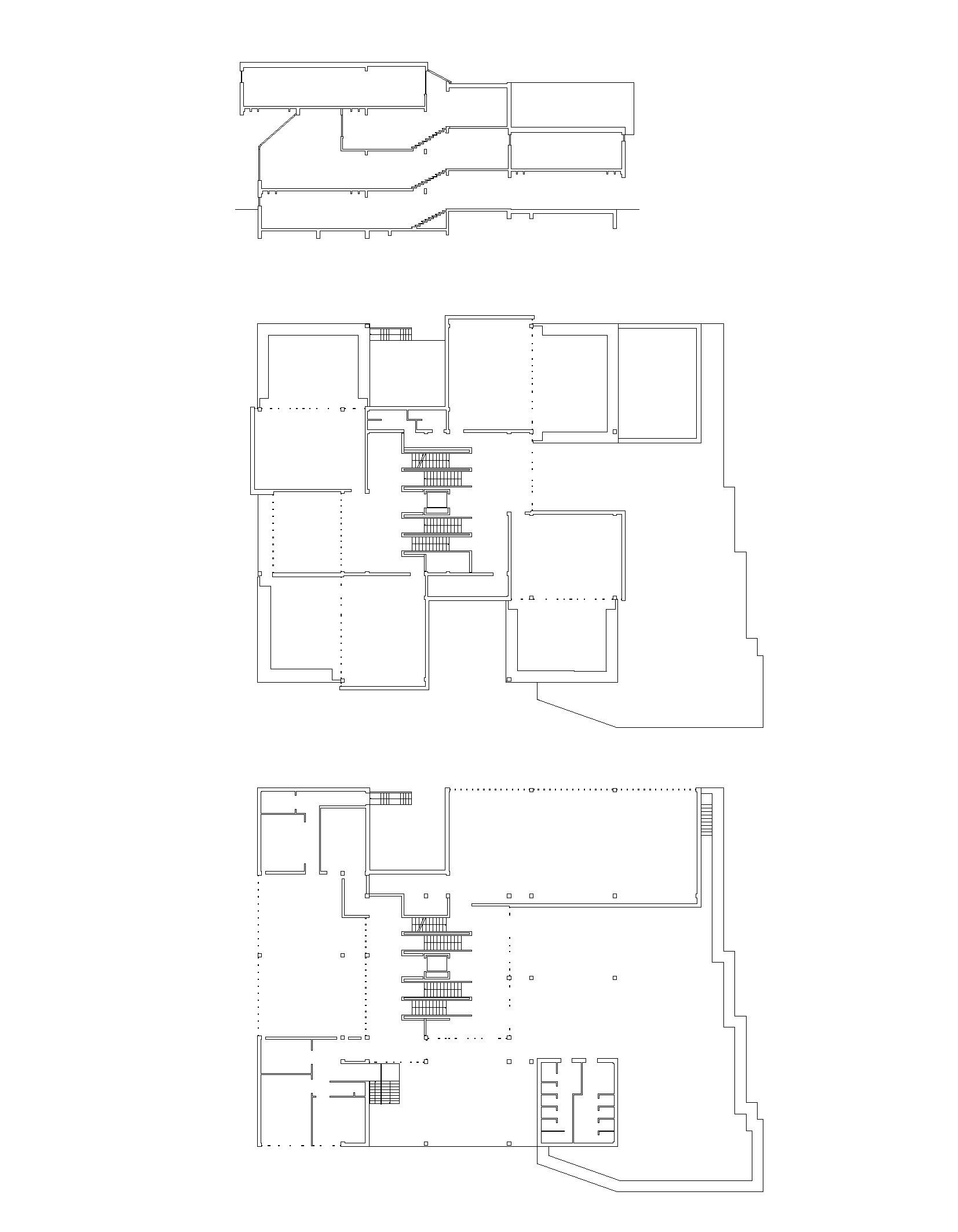

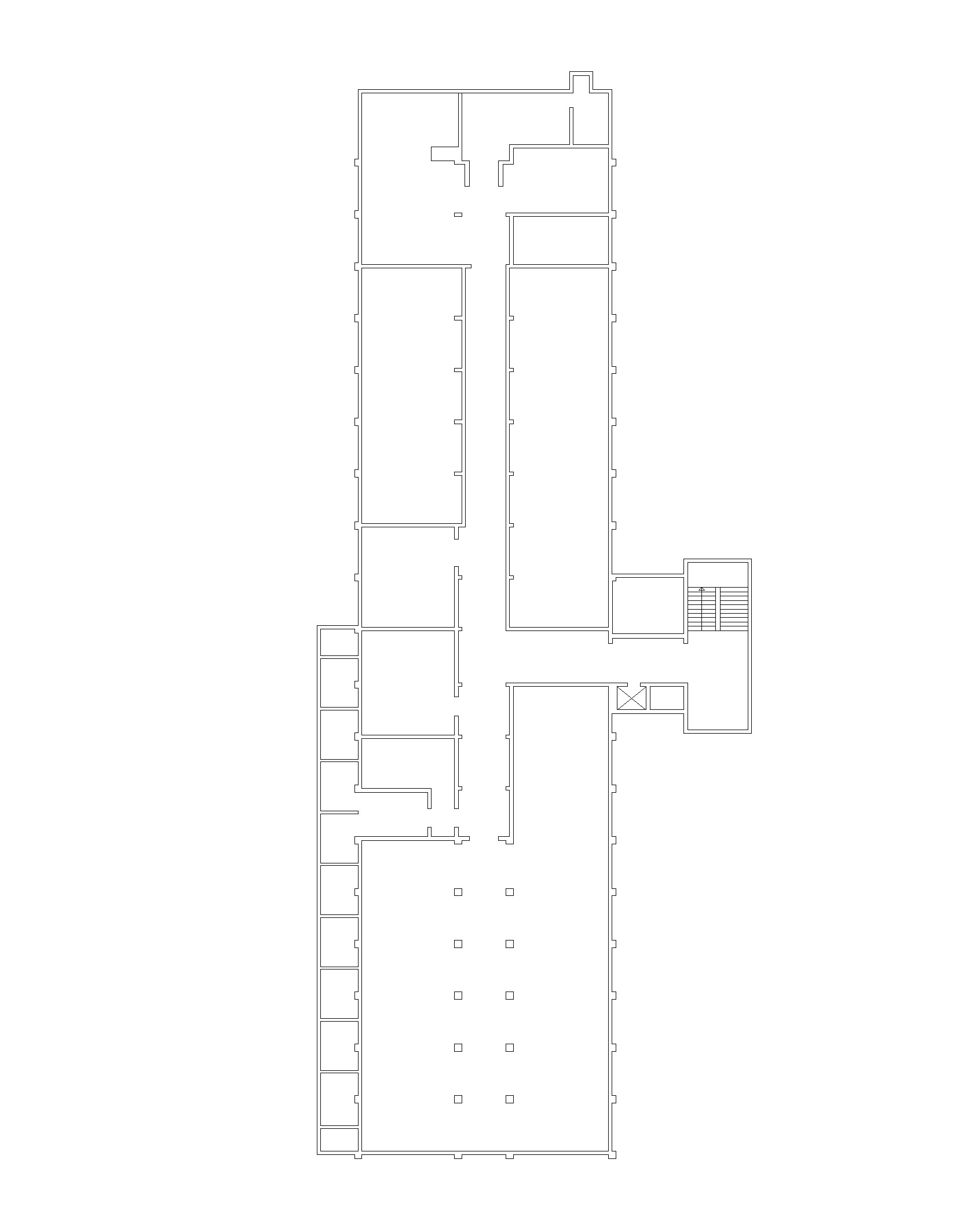

CAVE

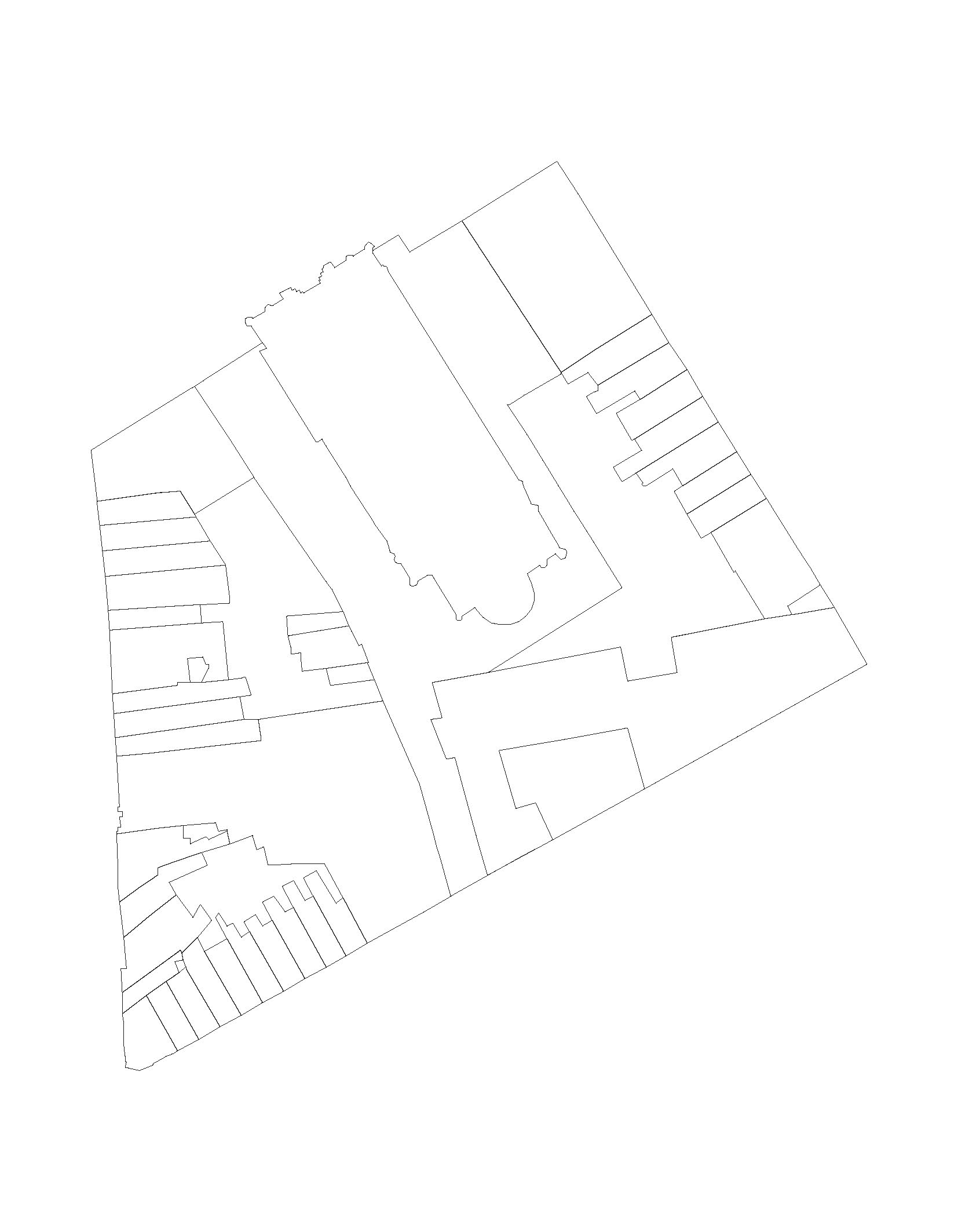

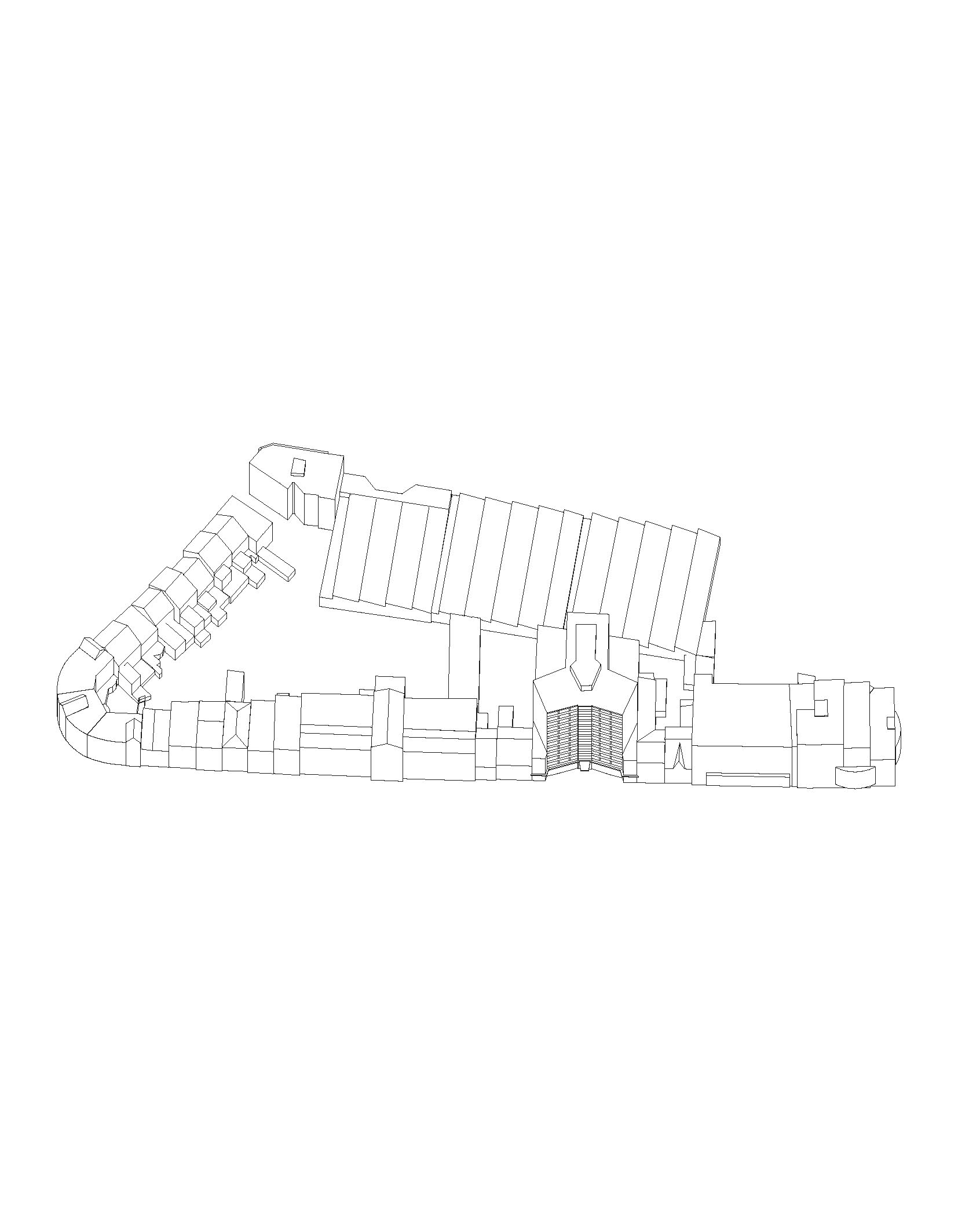

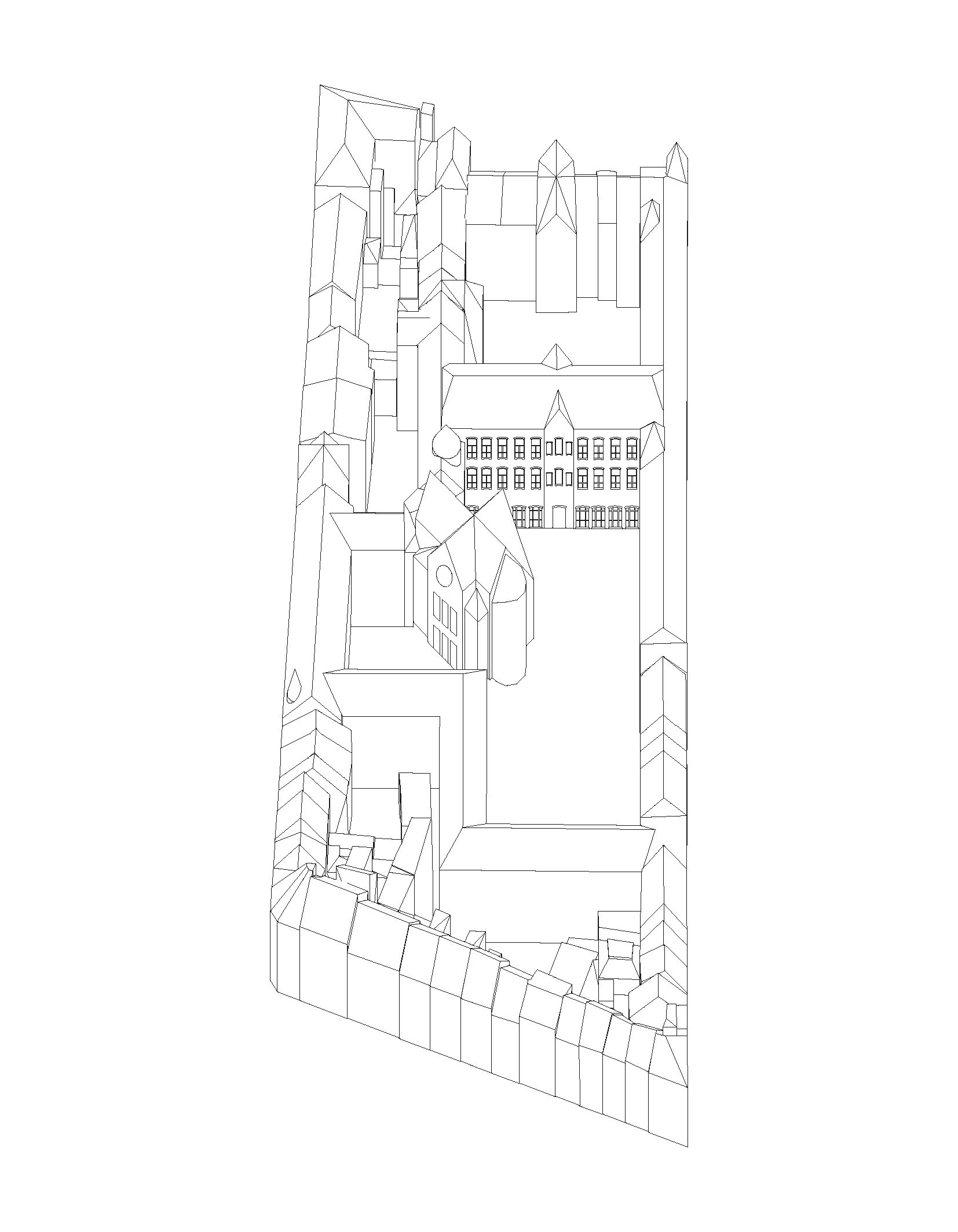

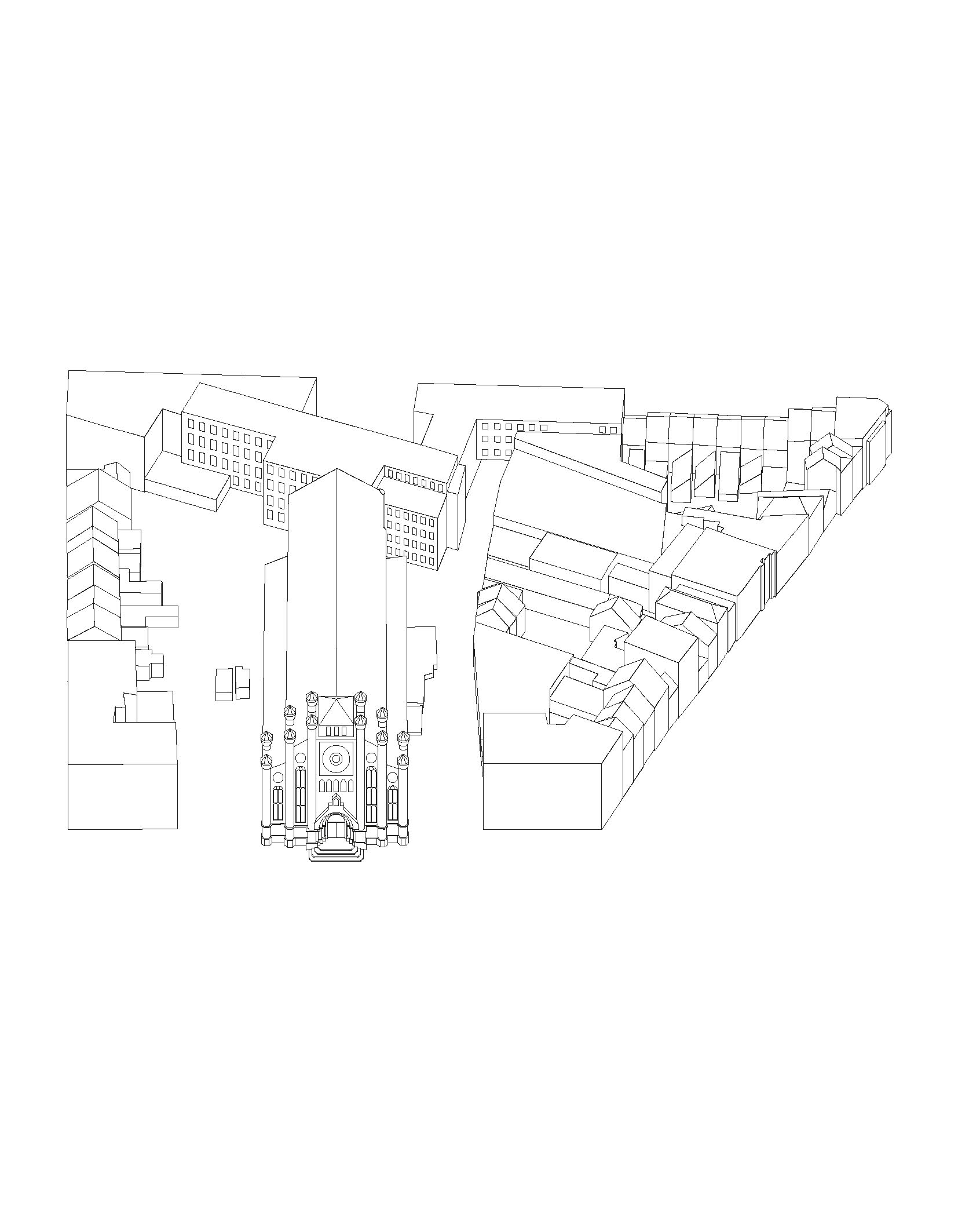

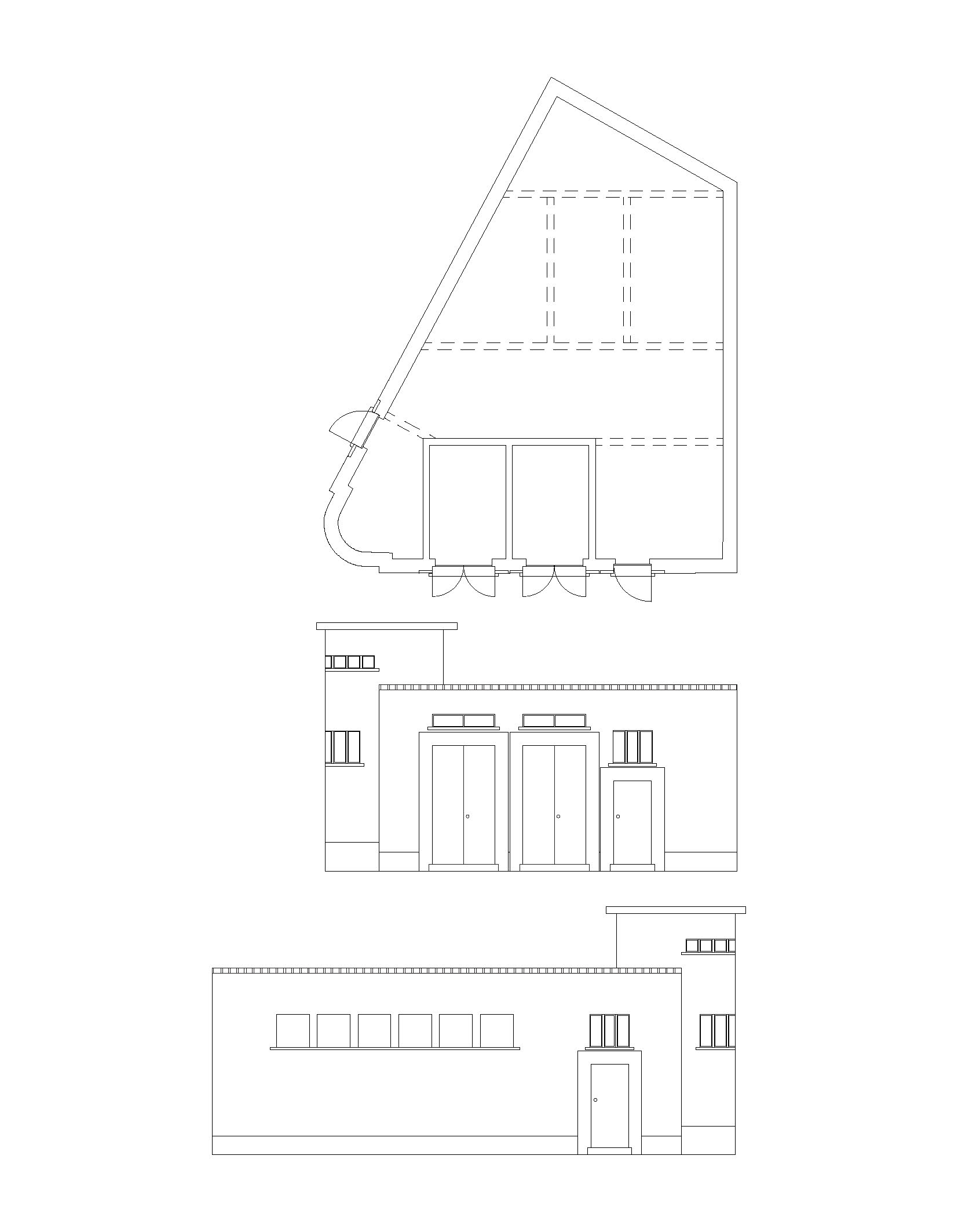

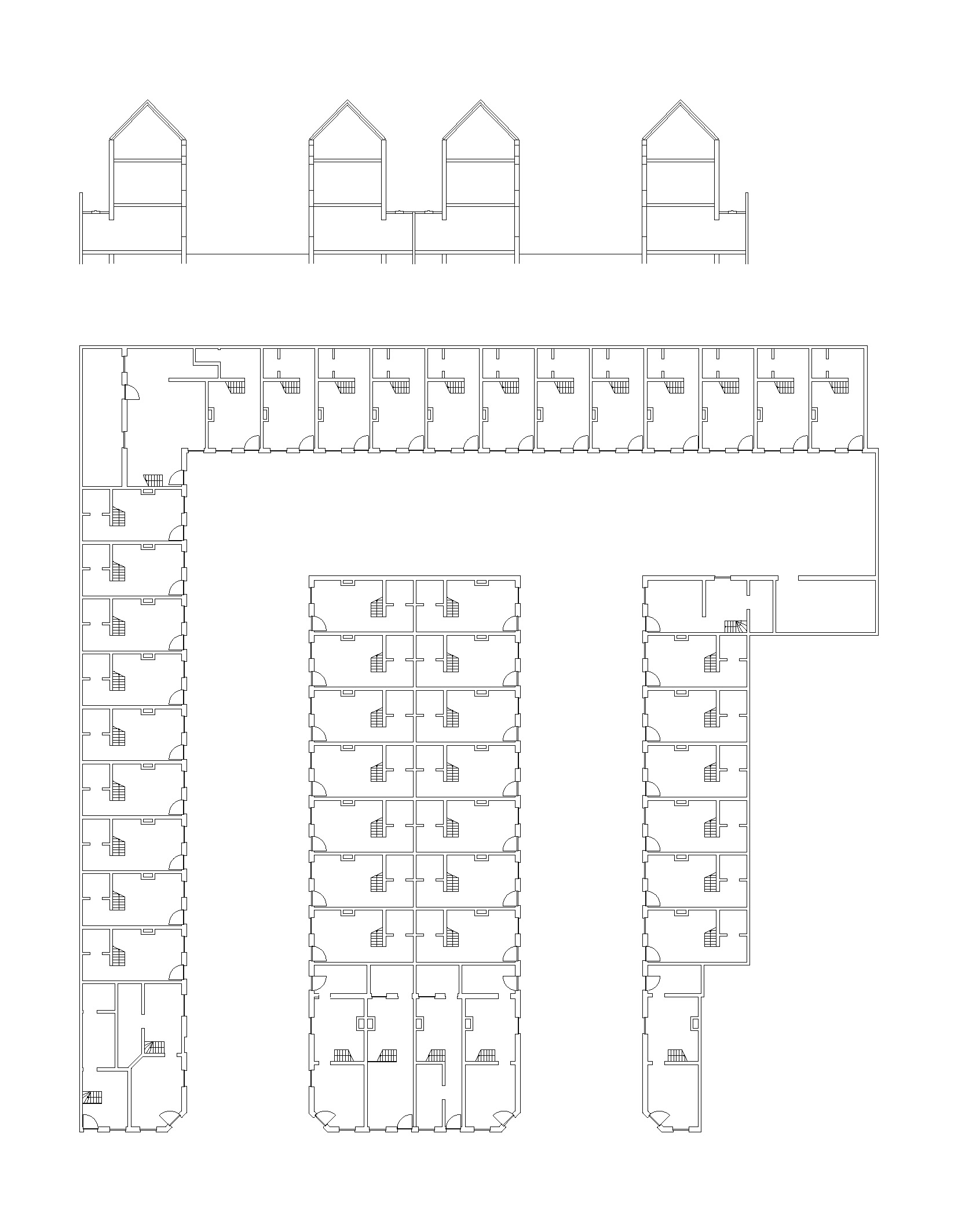

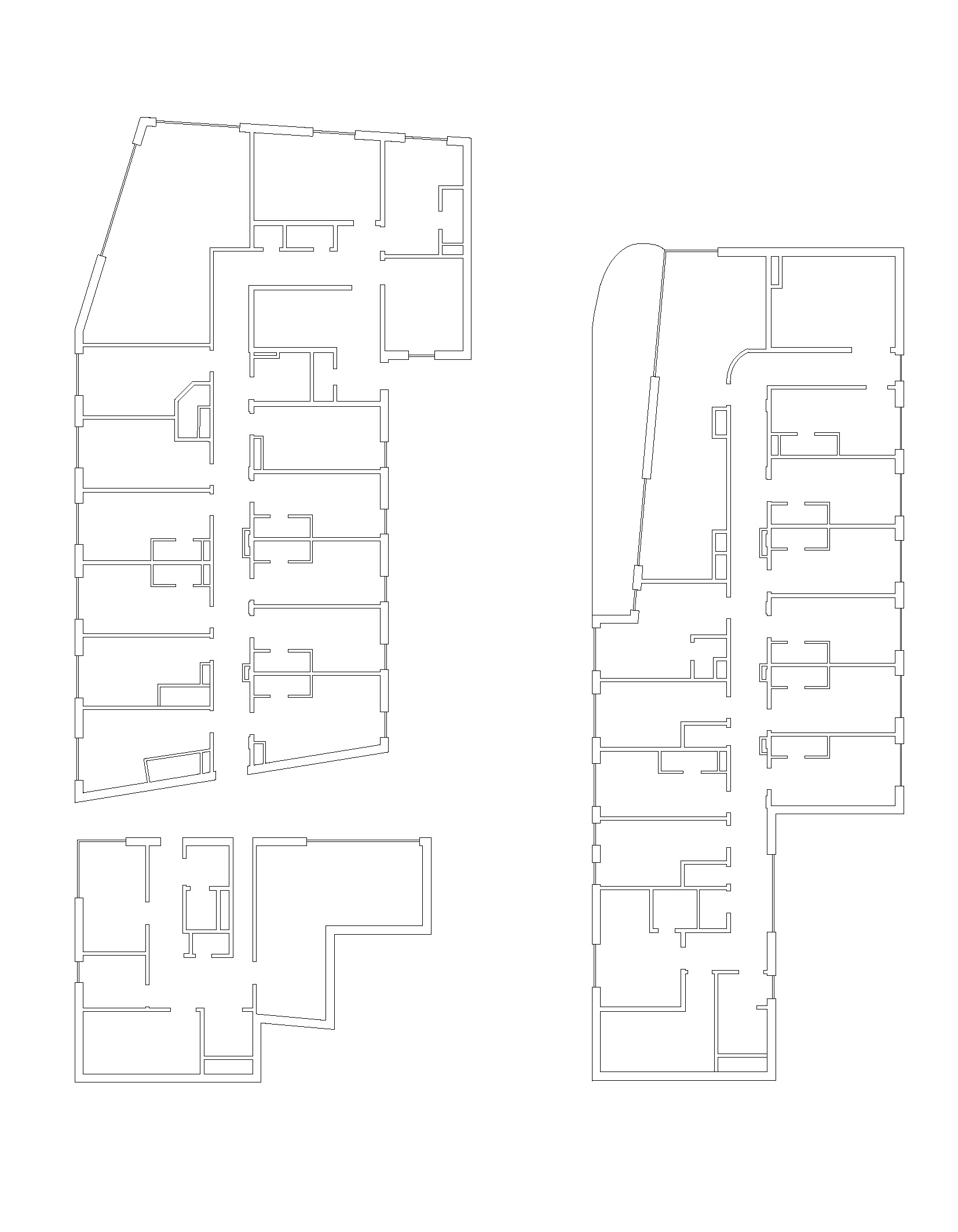

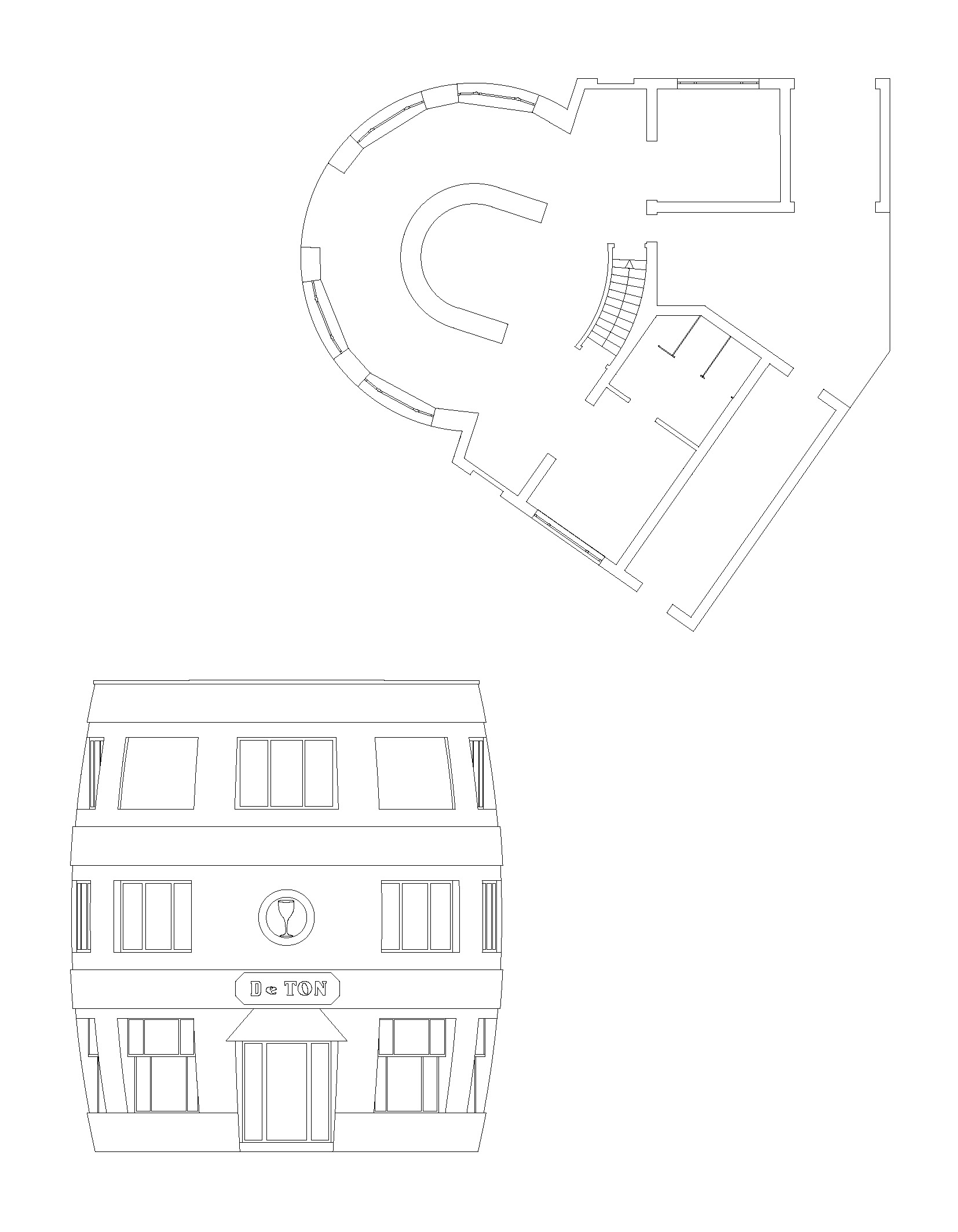

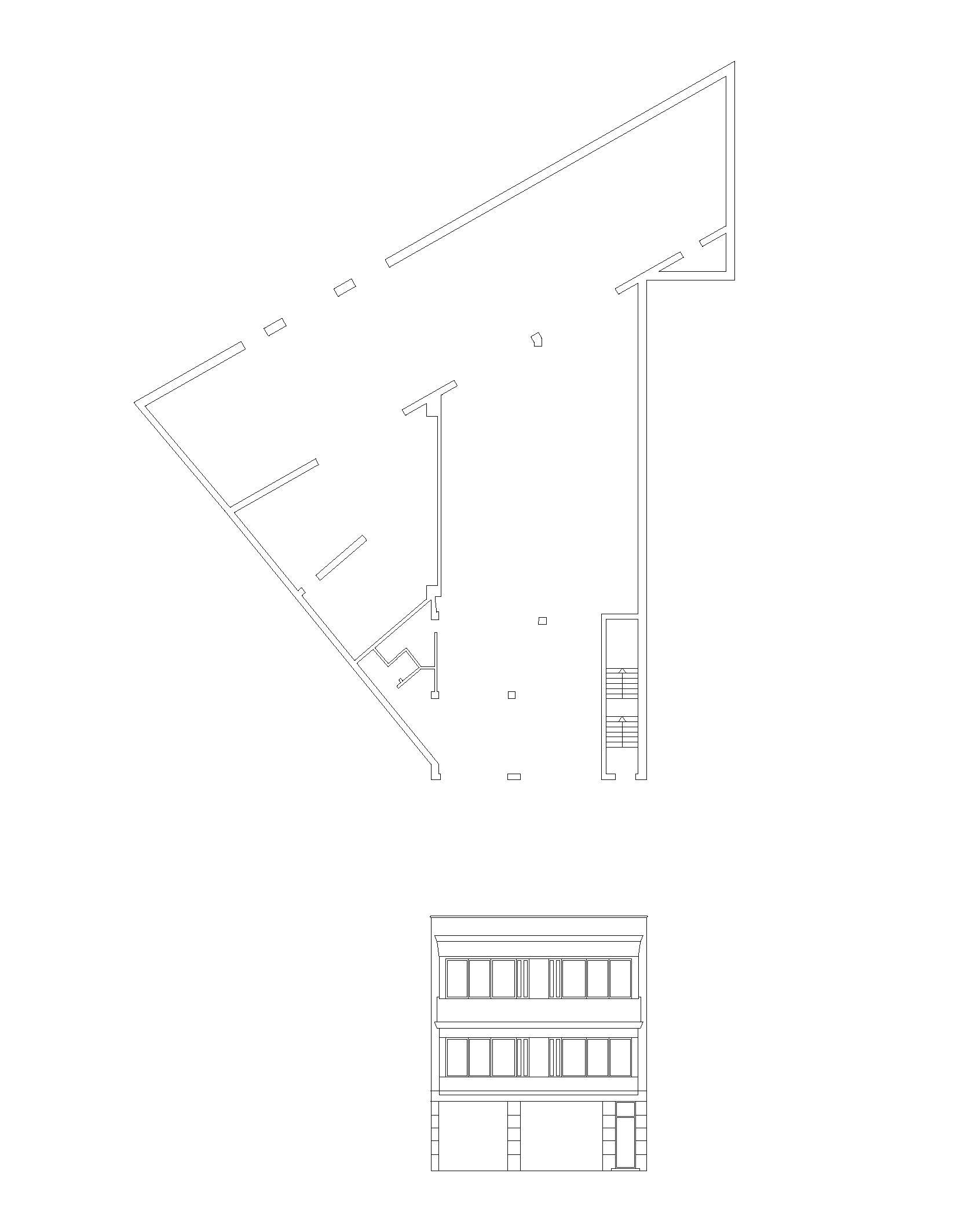

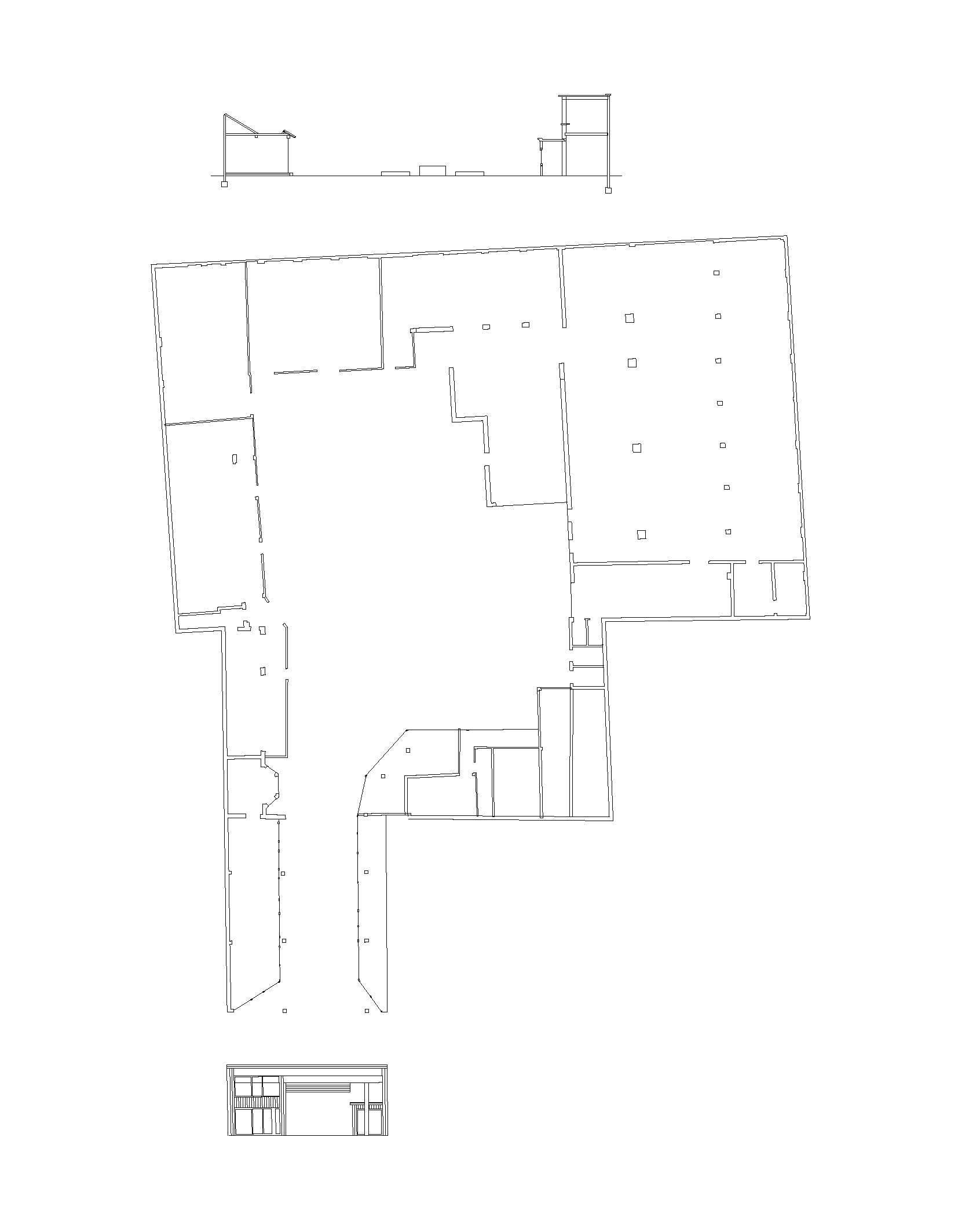

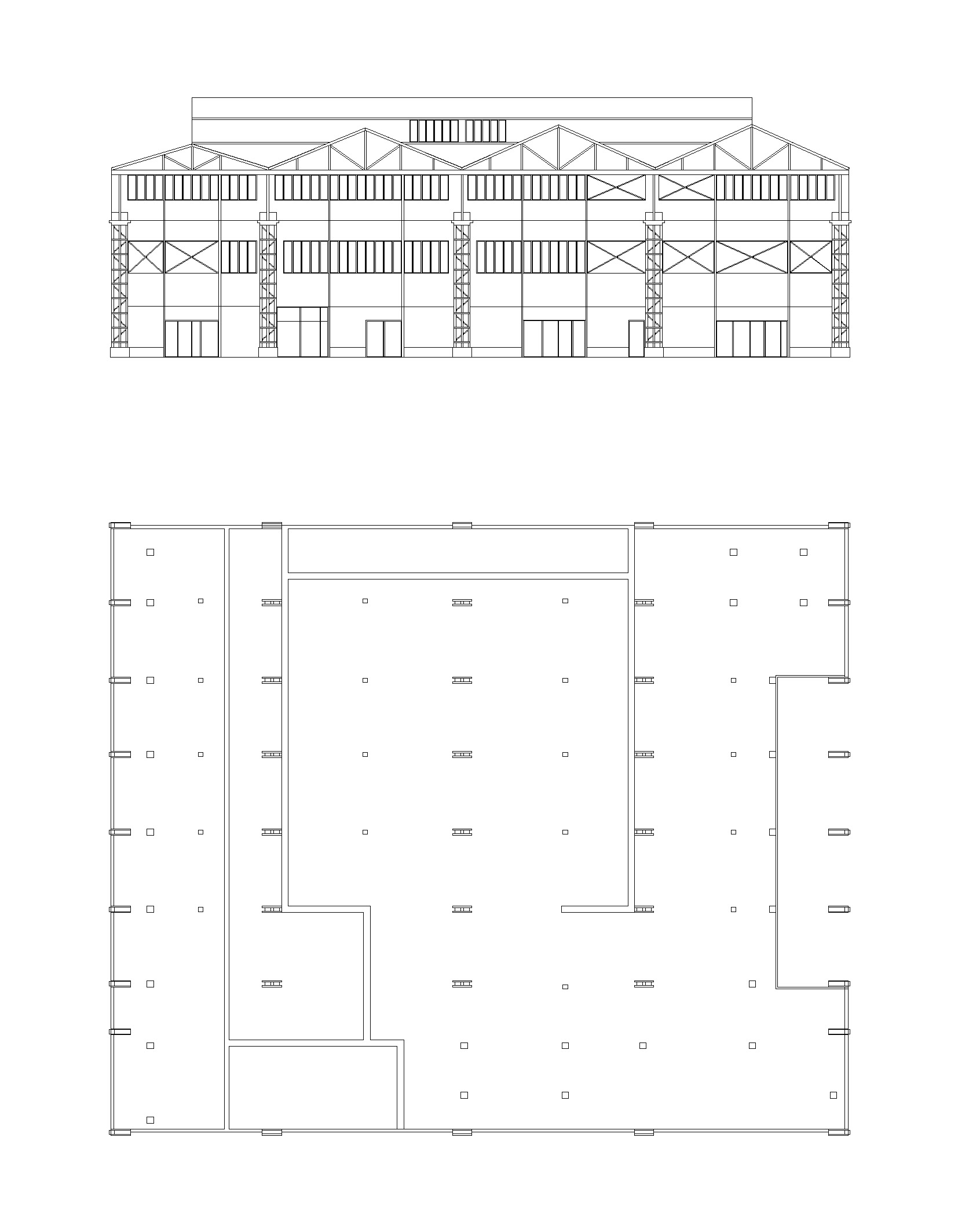

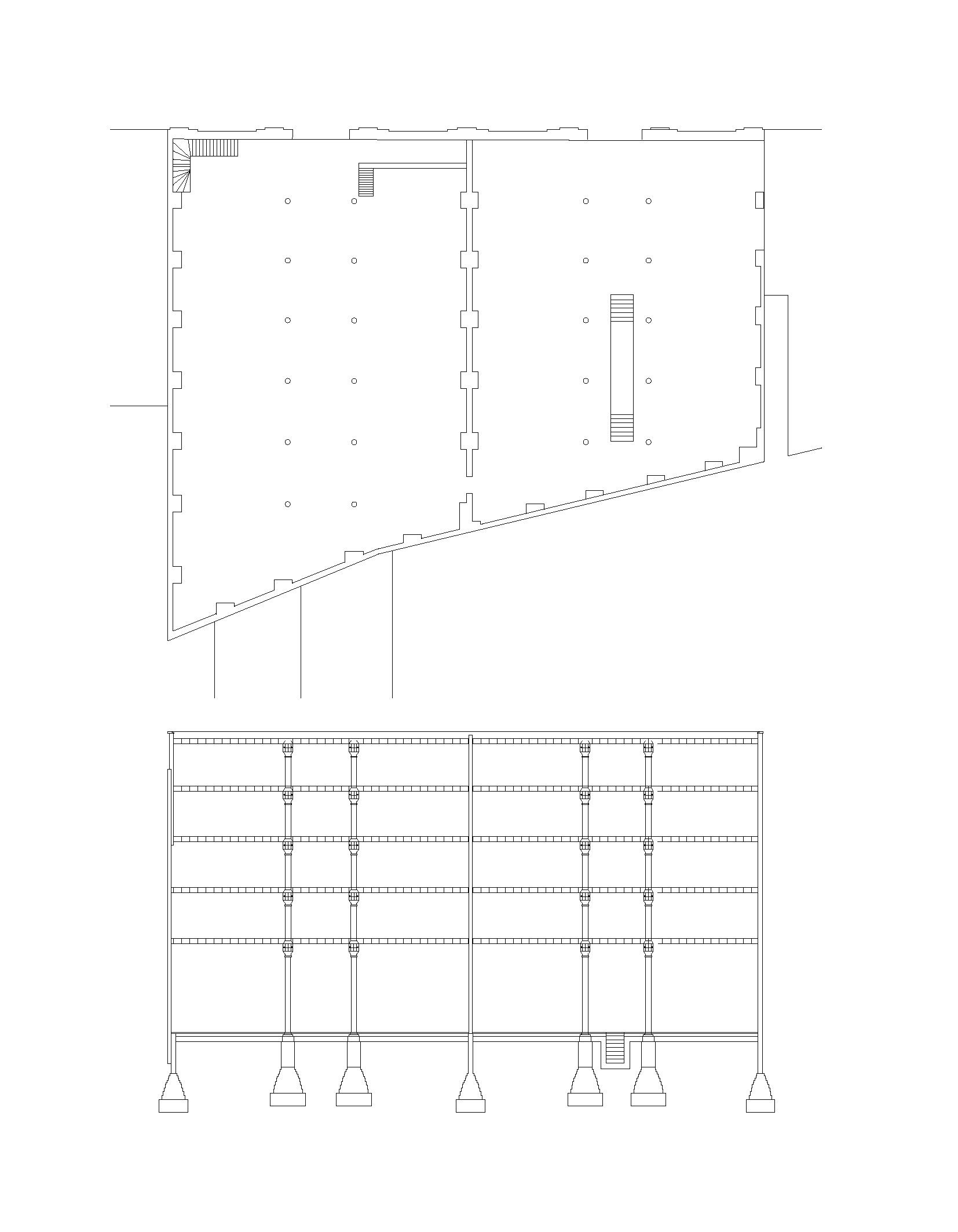

TENT

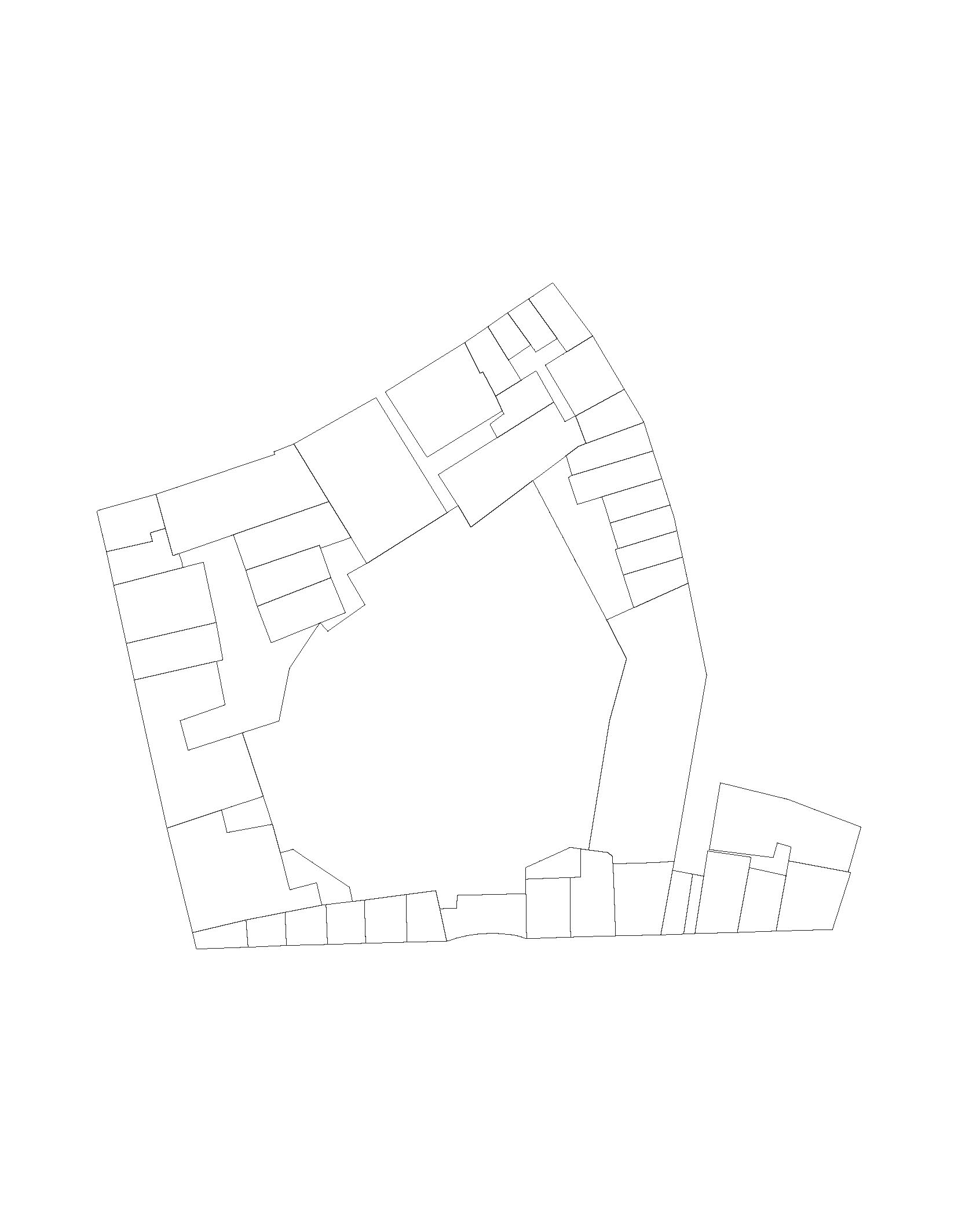

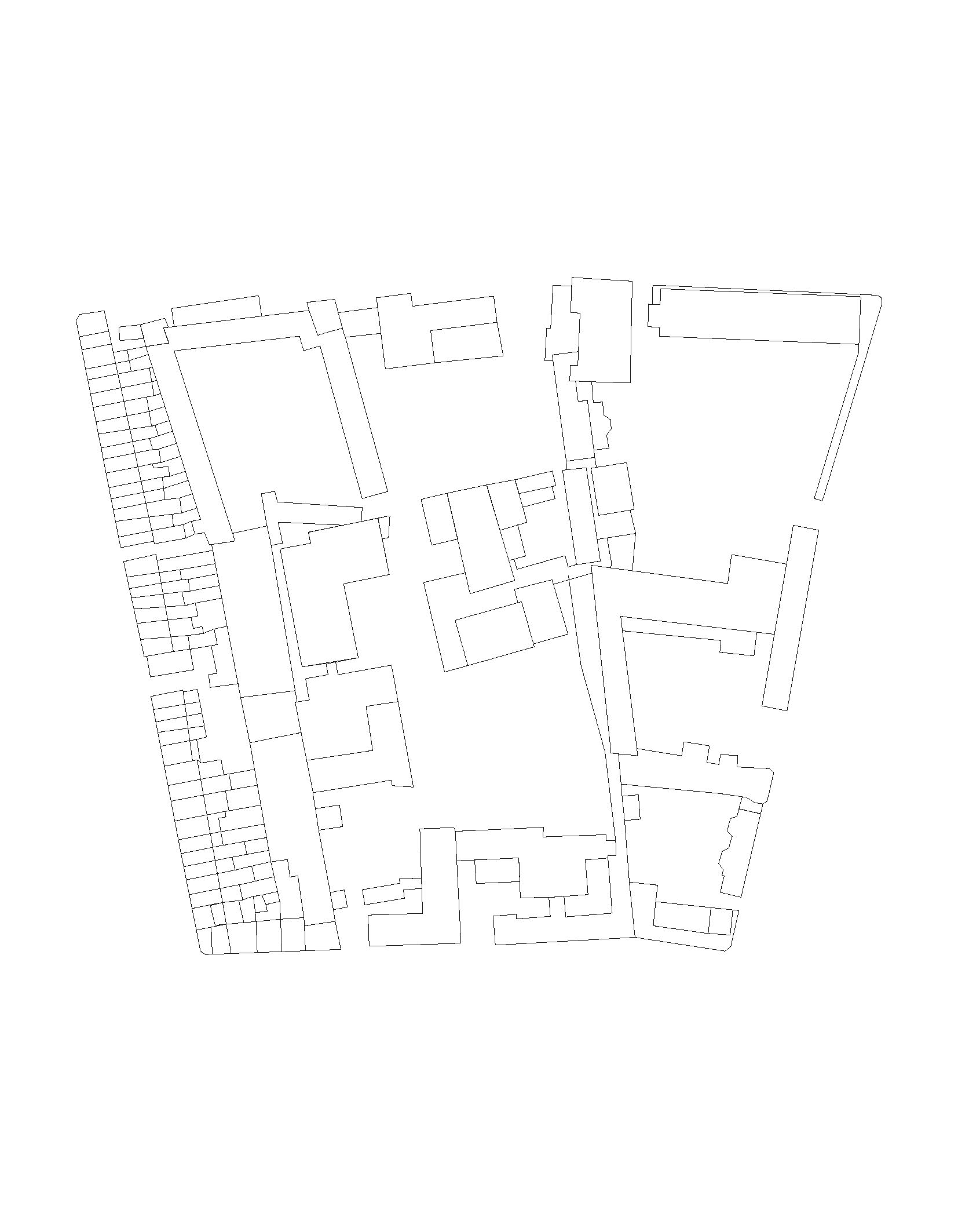

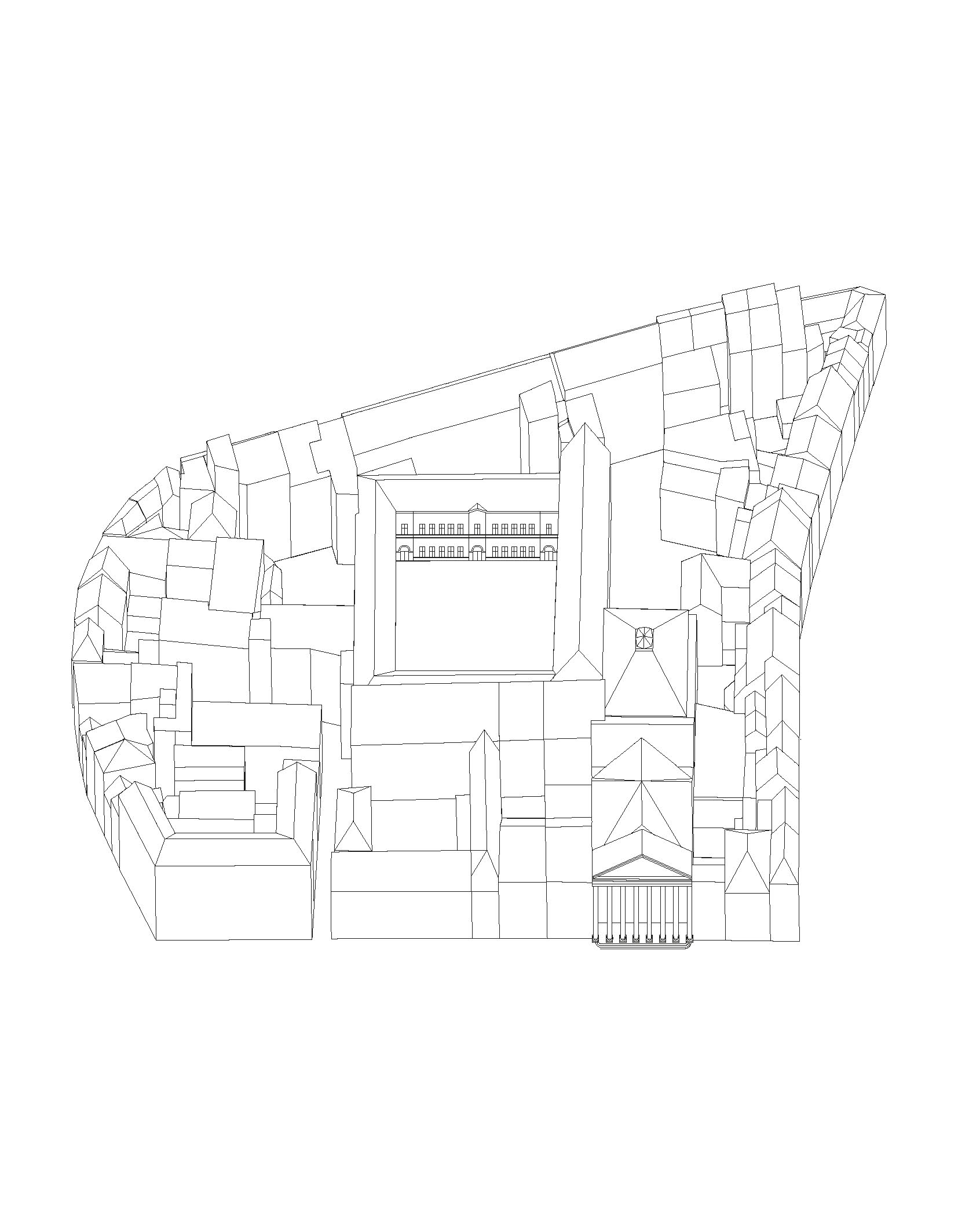

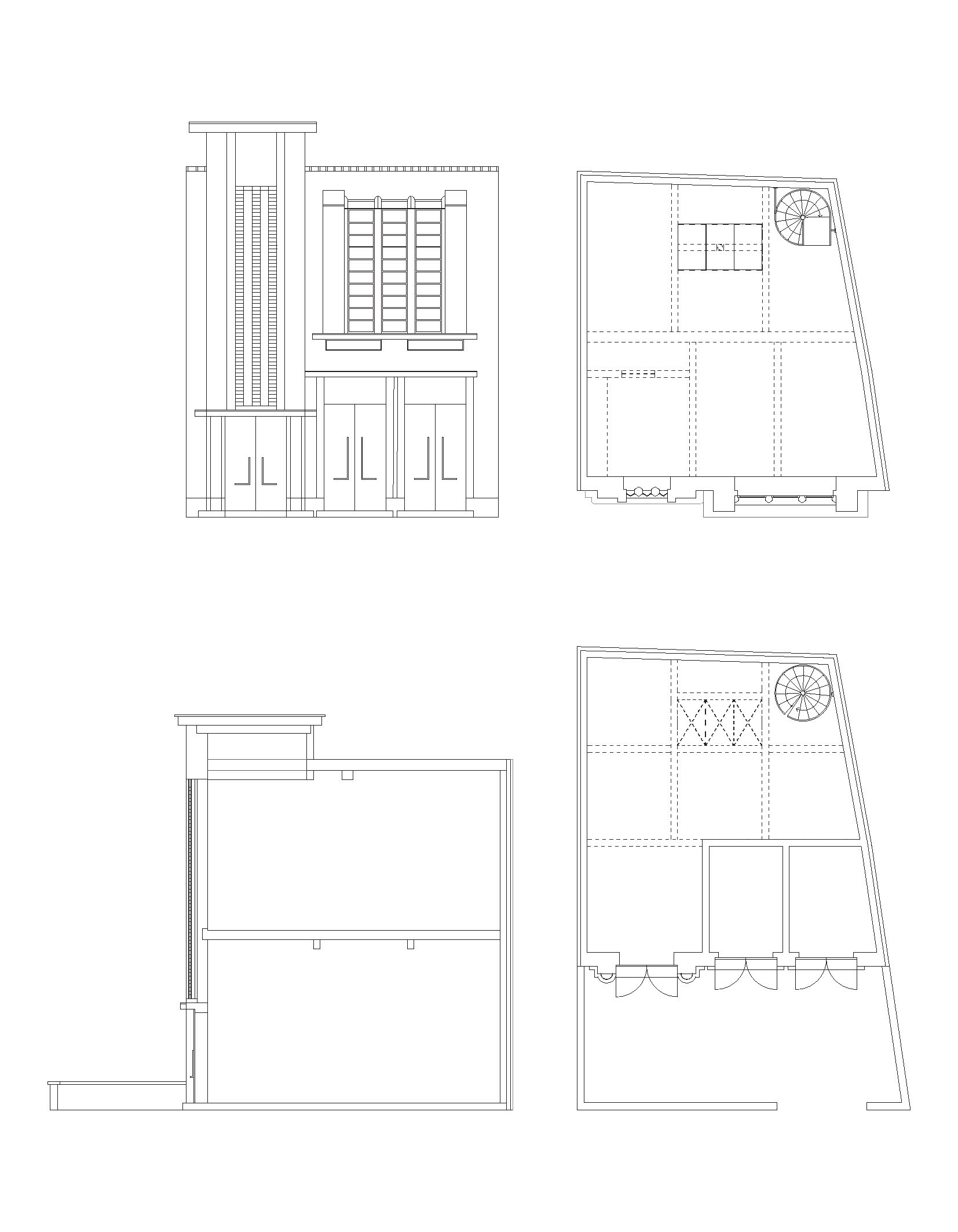

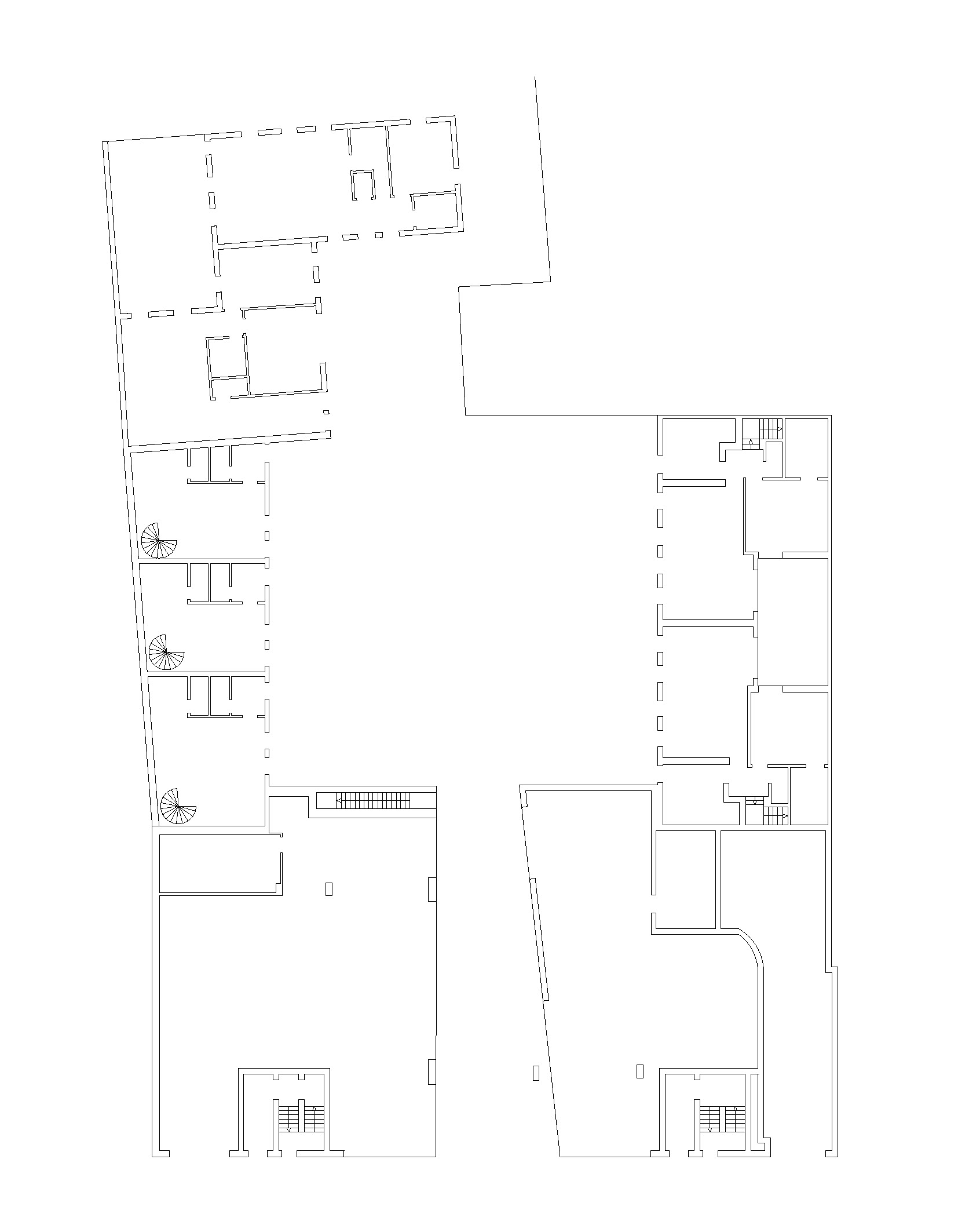

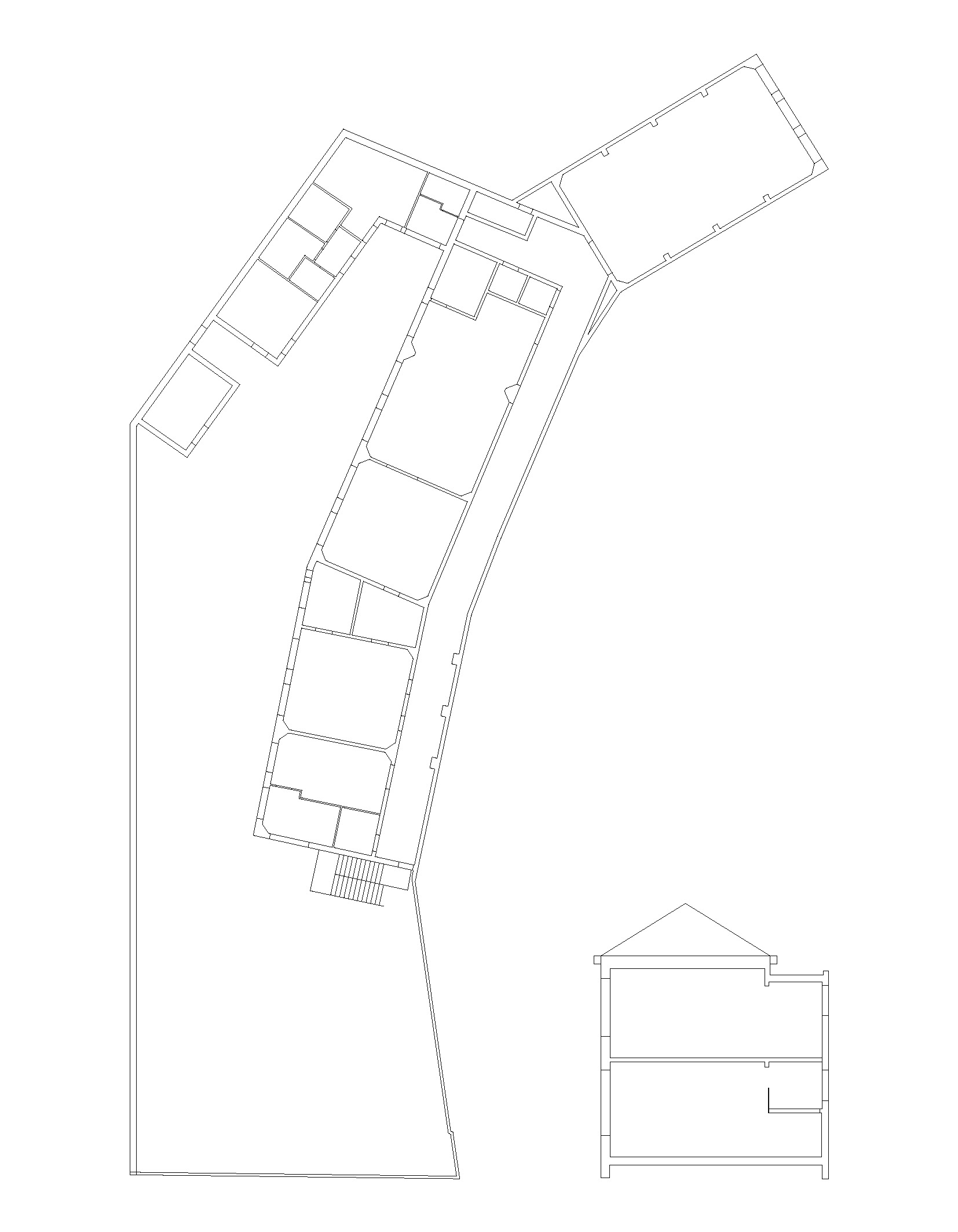

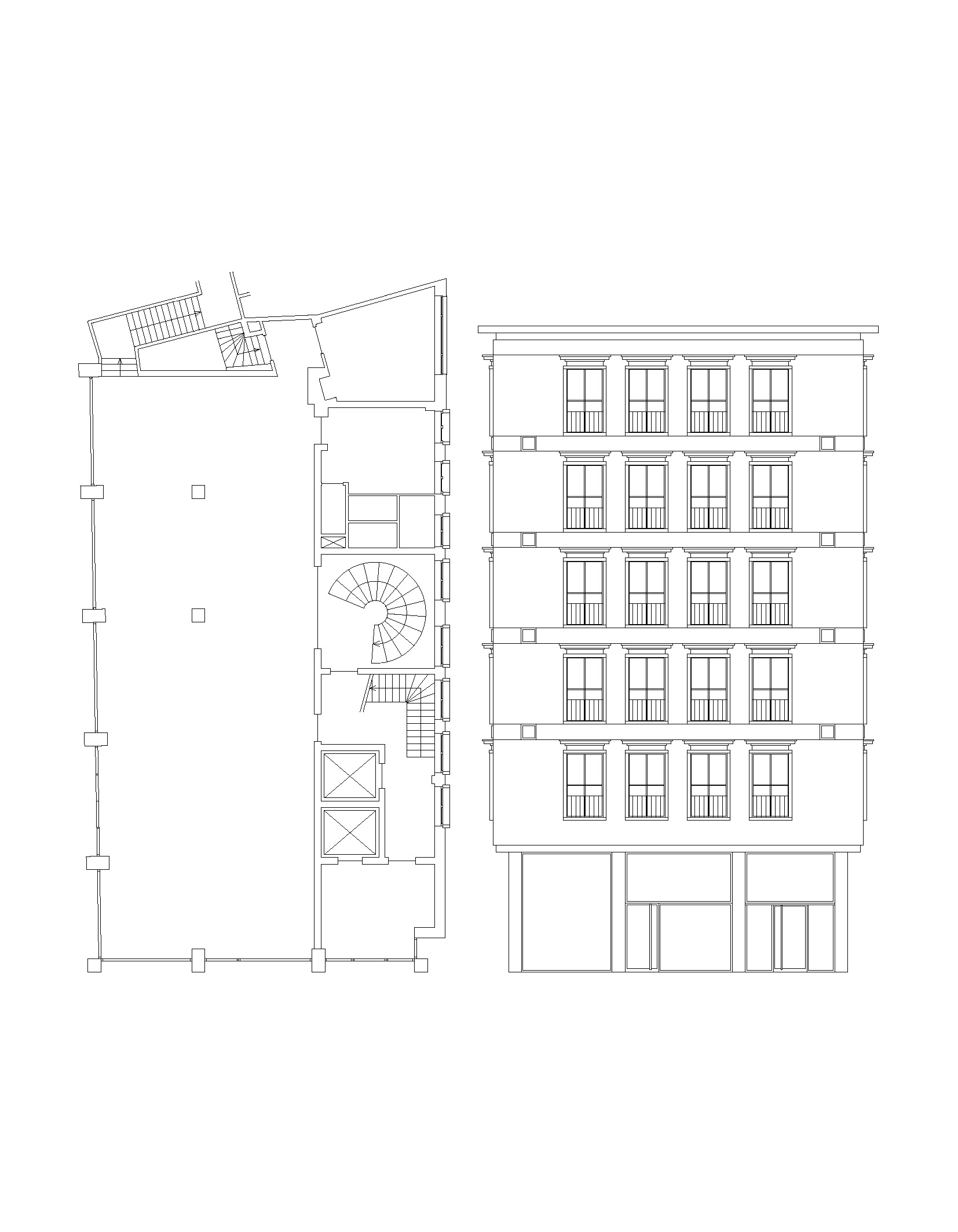

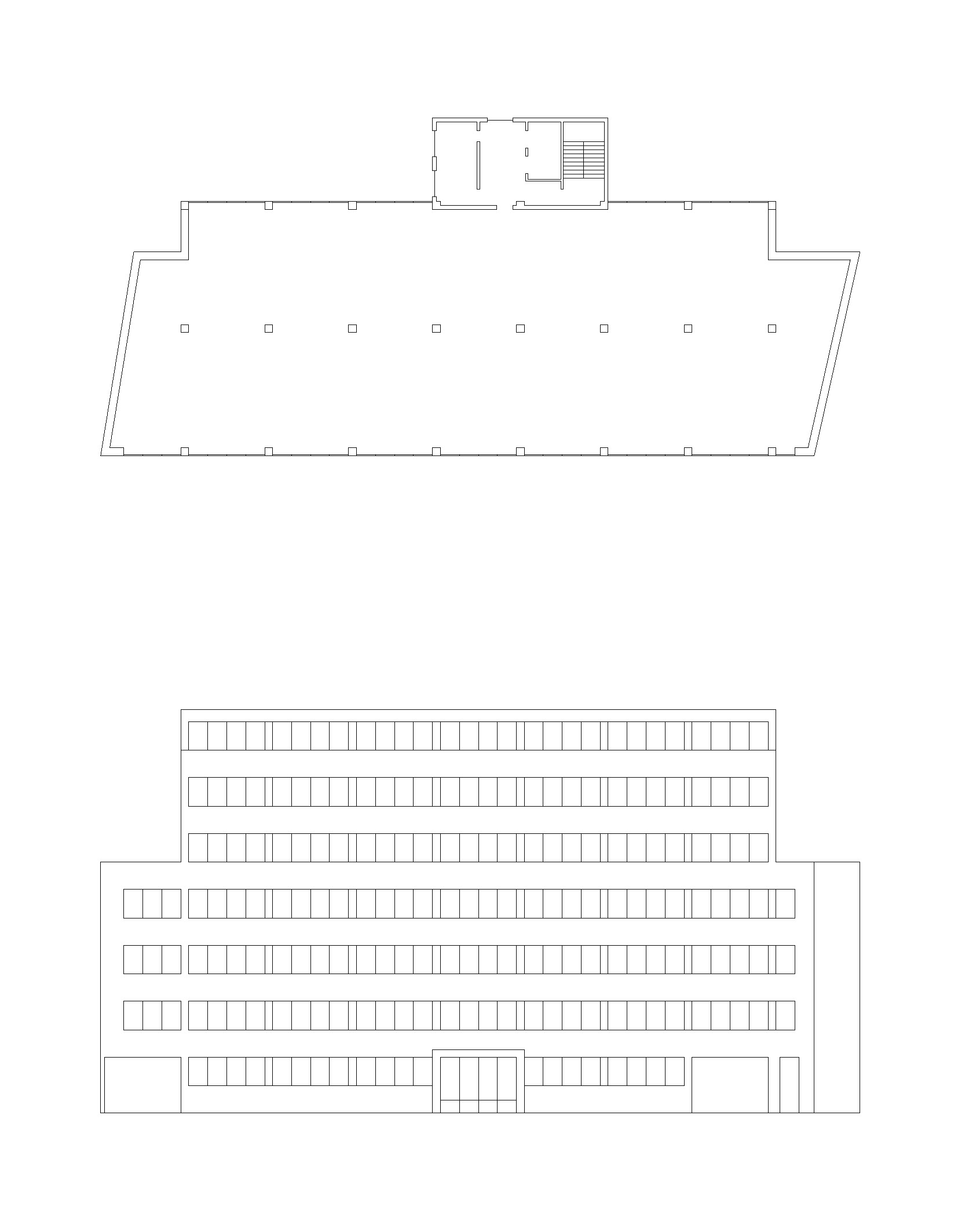

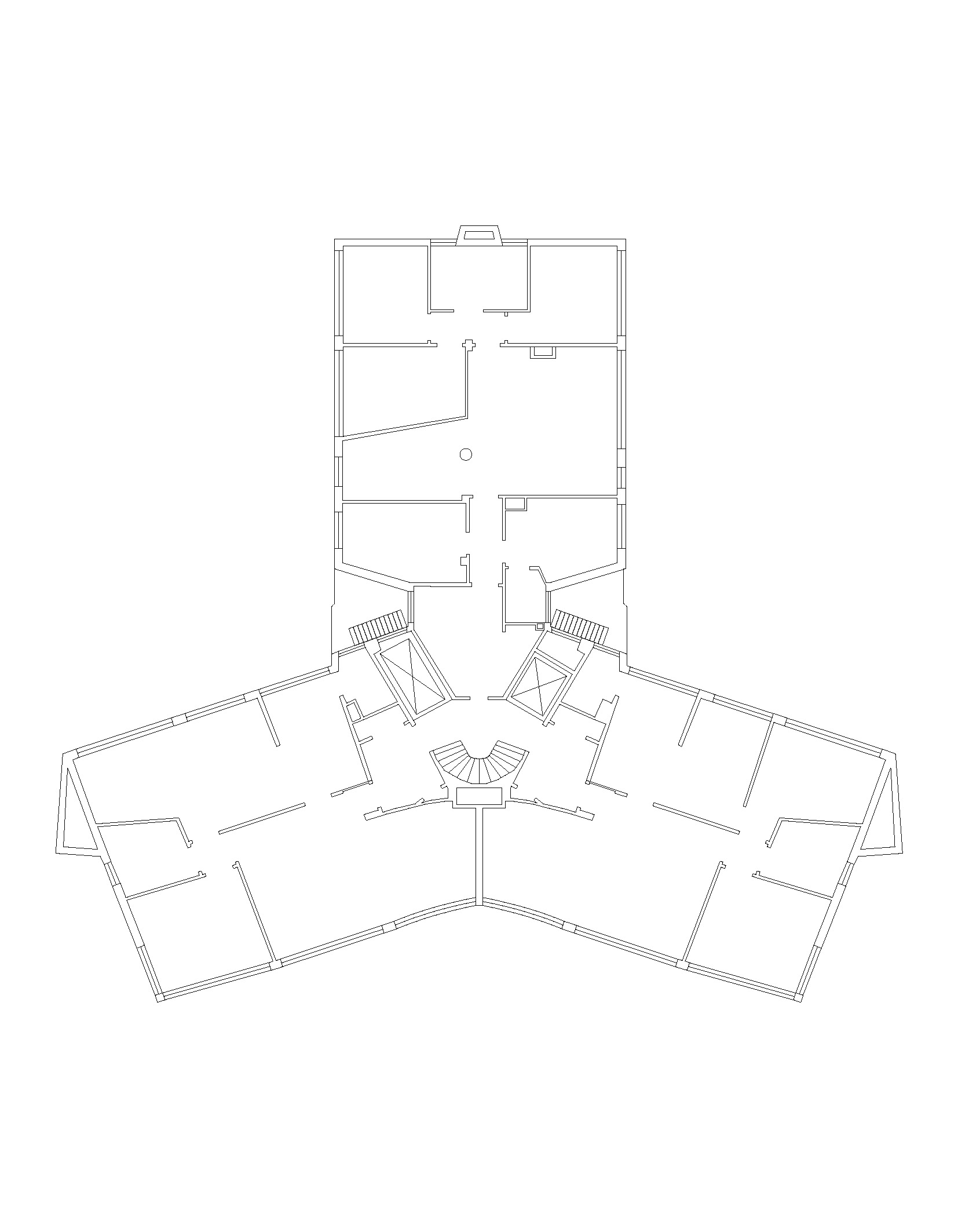

HYBRID

Jury

He (the architect) is initially trapped by the type because it is the way he knows. Later he can act on it. He can destroy it, transform it, respect it. But he starts from the type. The design process is a way of bringing elements of a typology – the idea of a formal structure – into the precise state that characterizes the single work.

By looking at architectural objects as groups, as types, susceptible to differentiation in their secondary aspects, the partial obsolescences appearing in them can be appraised, and consequently one can act to change them. The type can thus be thought of as a frame within which change operates, a necessary term to the continuing dialectic required by history. From this point of view, the type, rather than being a “frozen mechanism” to produce architecture, becomes a way of denying the past, as well as a way of looking at the future.

In this continuous process of transformation, the architect can extrapolate from the type, changing its use; he can distort the type by means of a transformation of scale; he can overlap different types to produce new ones. He can use formal quotations of a known type in a different context, as well as create new types by a radical change in the techniques already employed. The list of different mechanisms is extensive – it is a function of inventiveness of architects.

— Rafael Moneo, “On Typology,” Oppositions; no. 13 (Summer 1978), p23-24

Brief

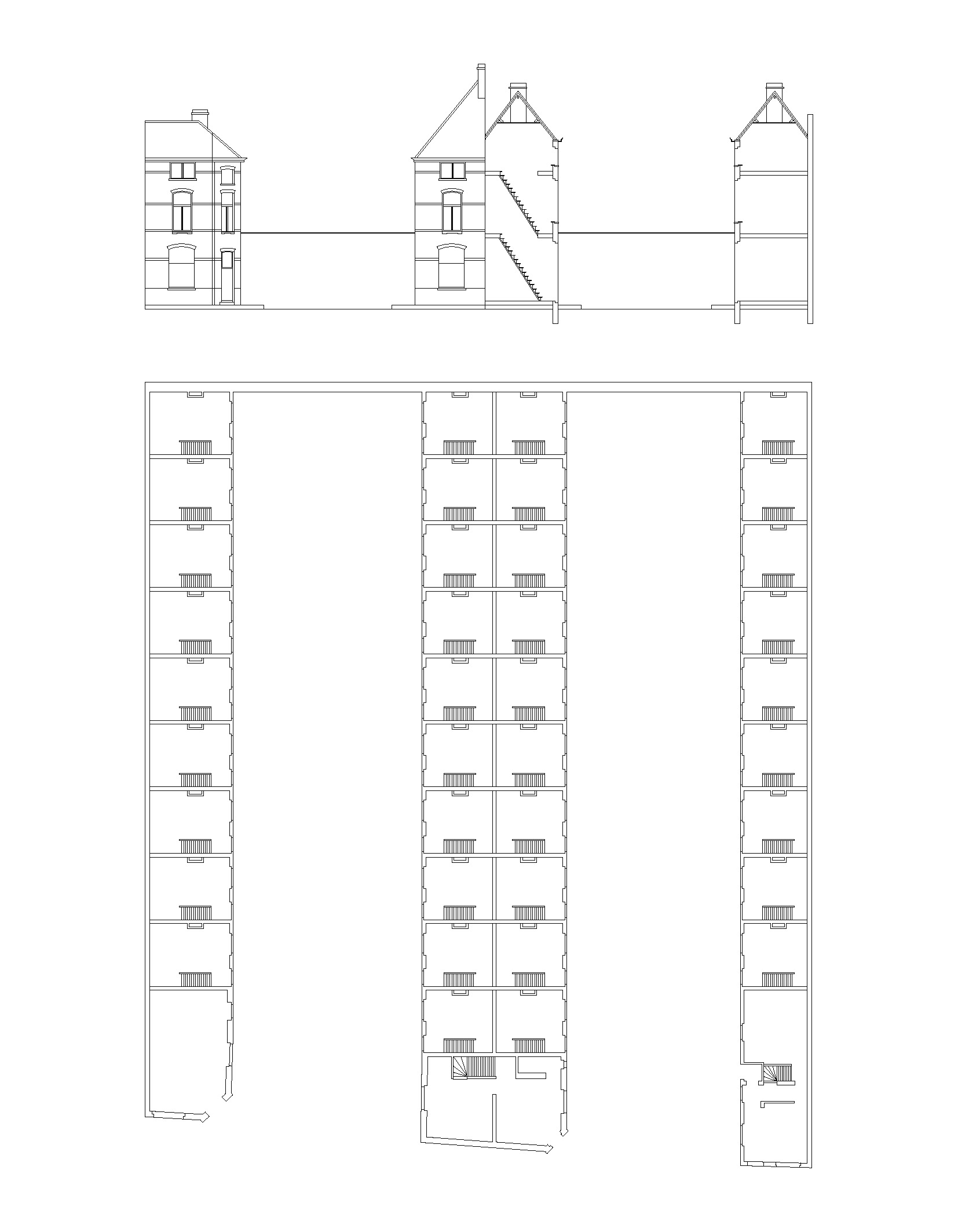

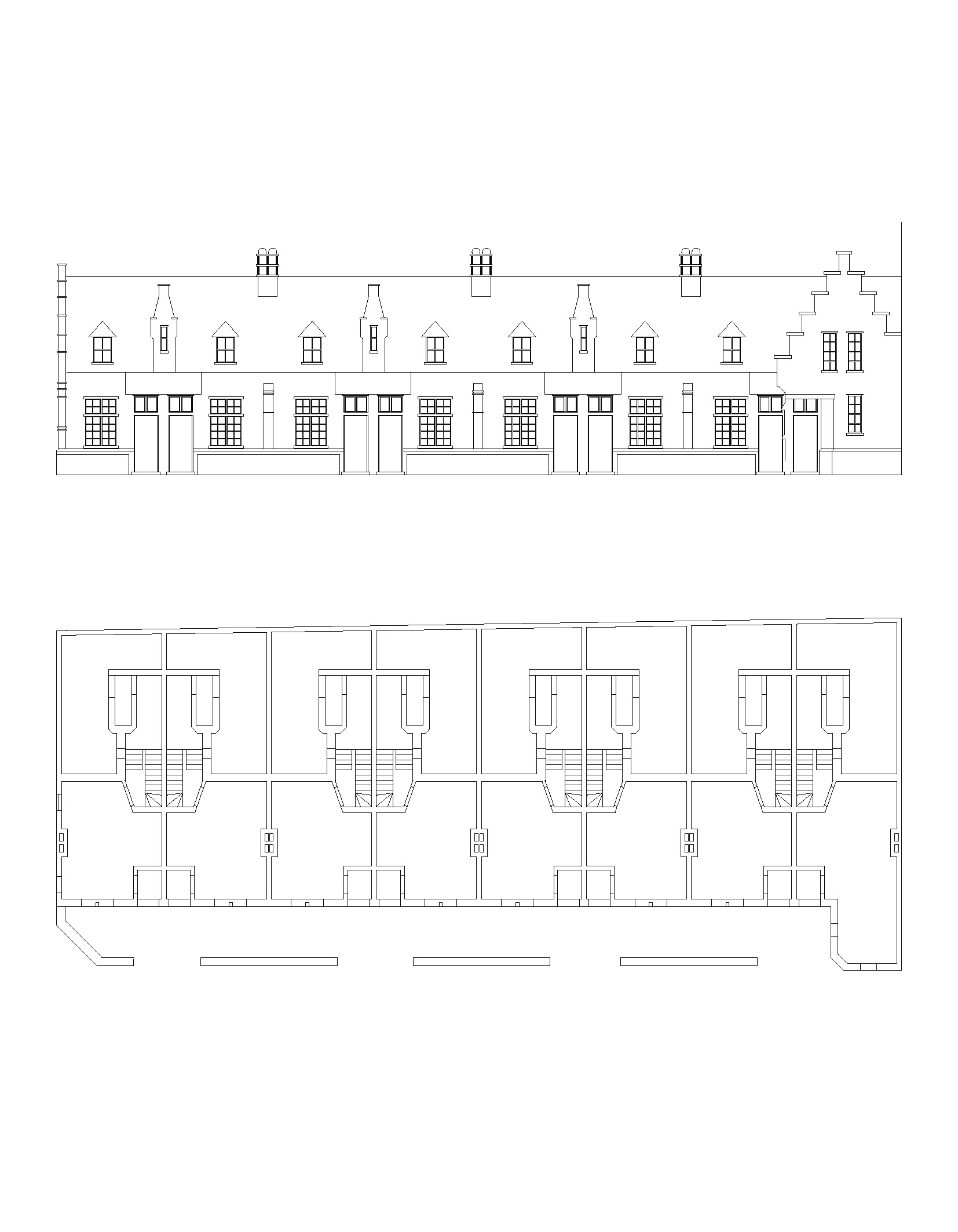

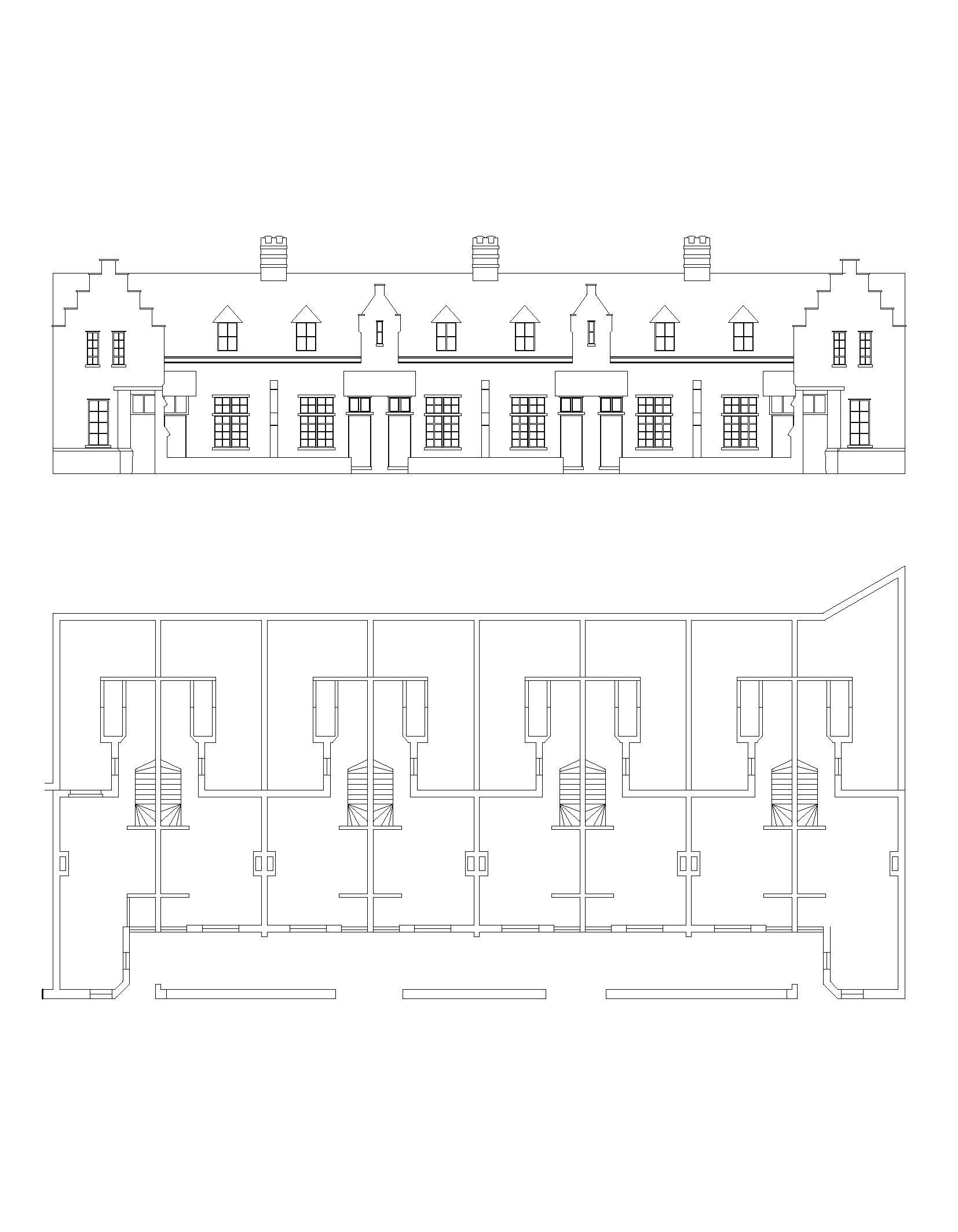

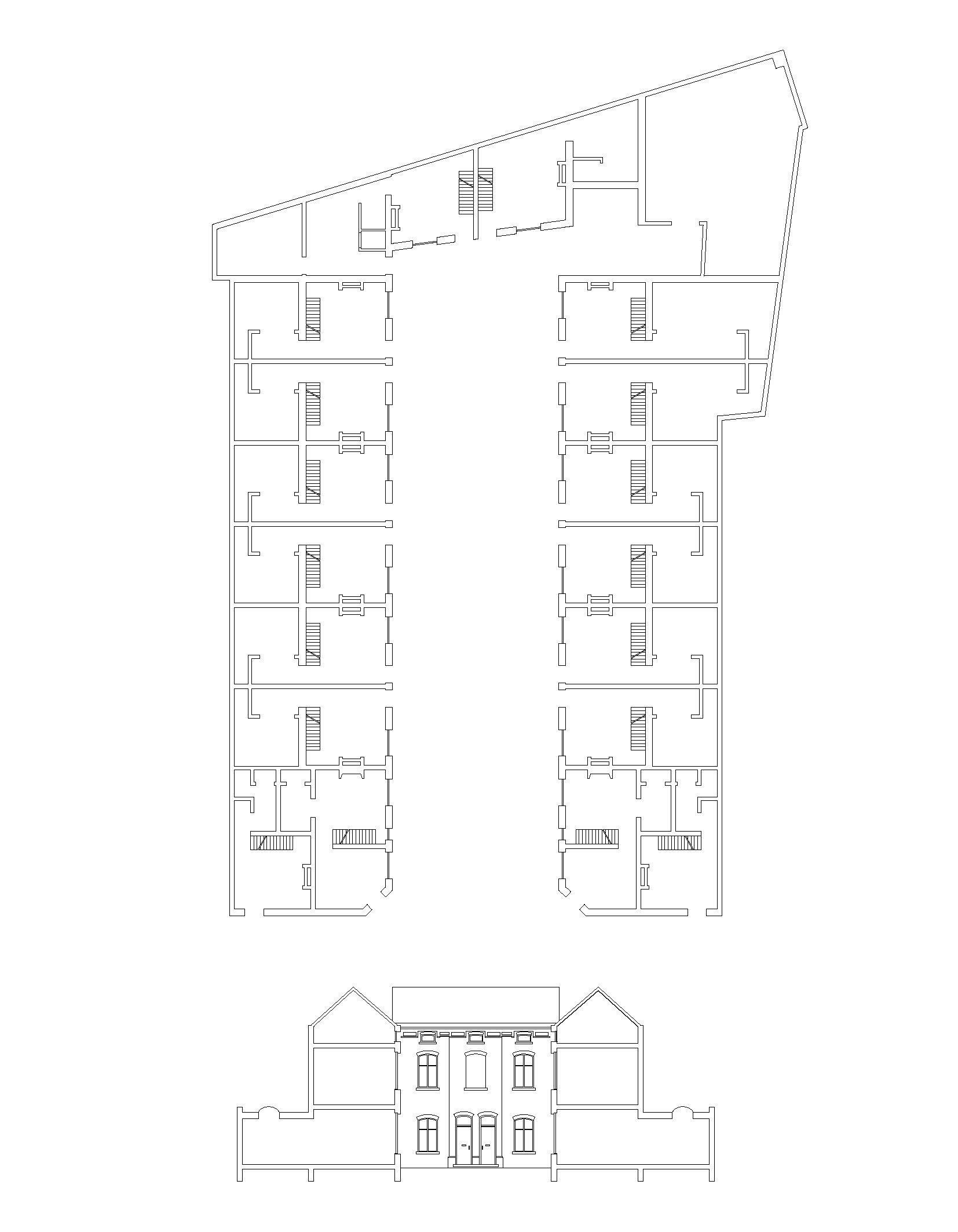

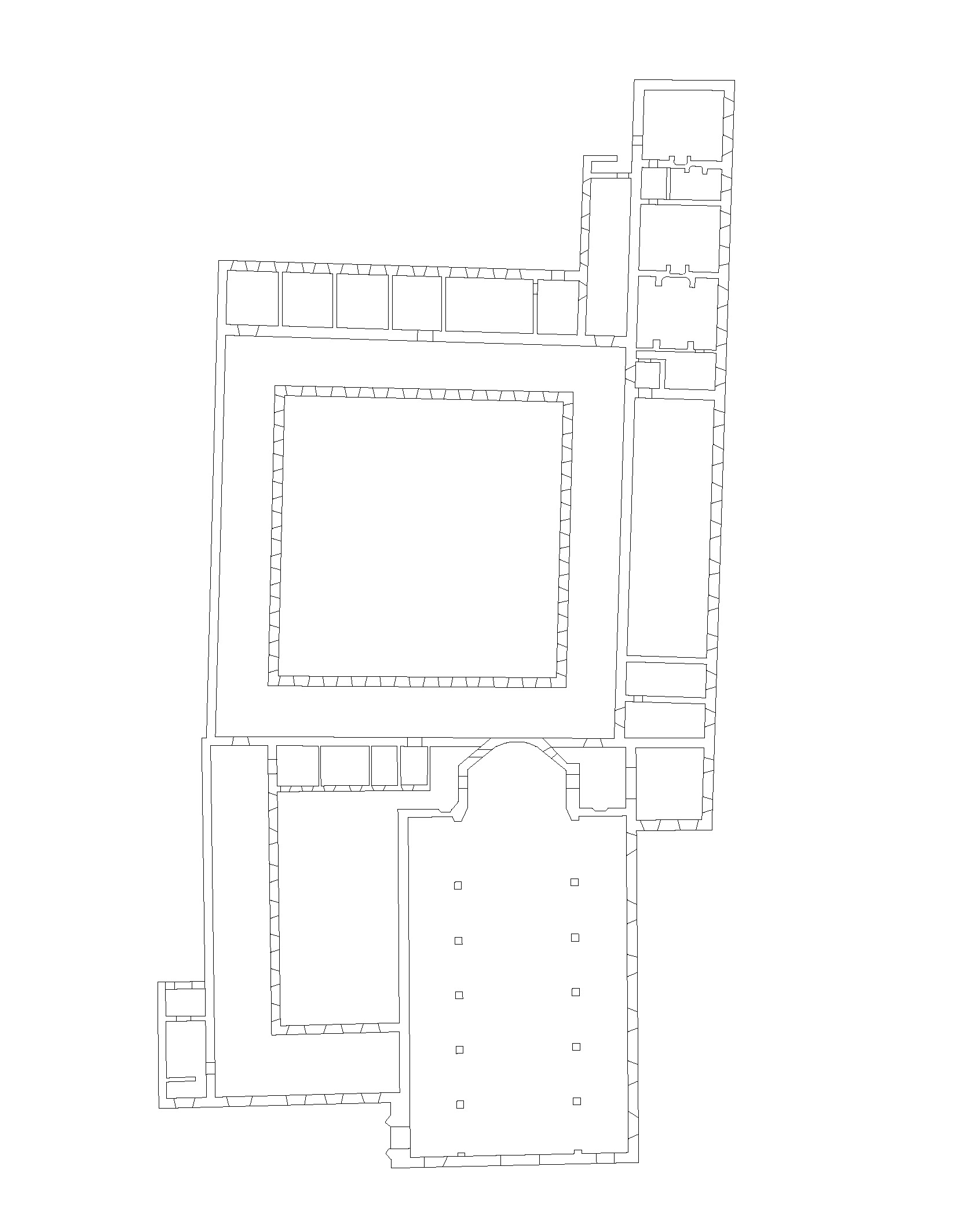

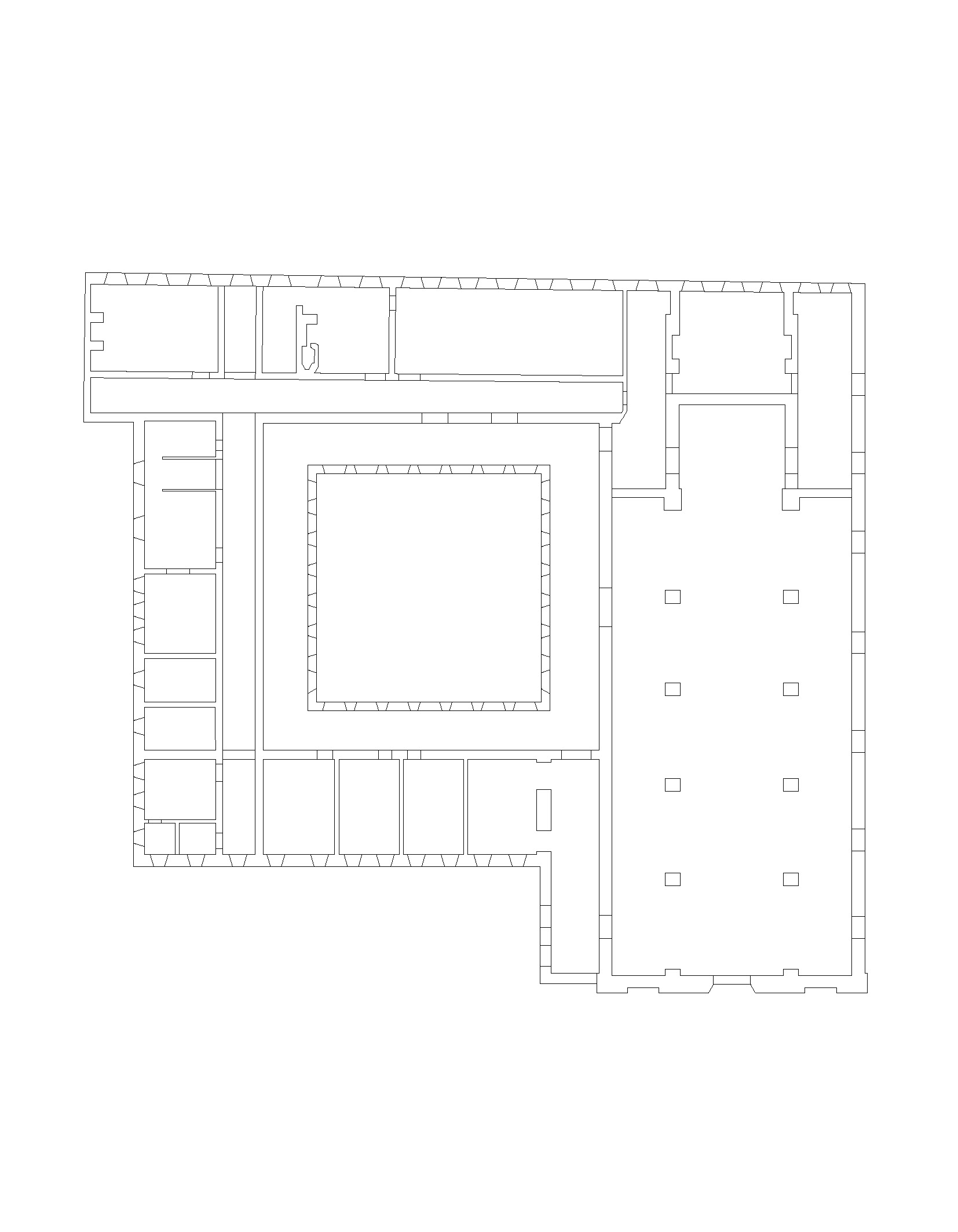

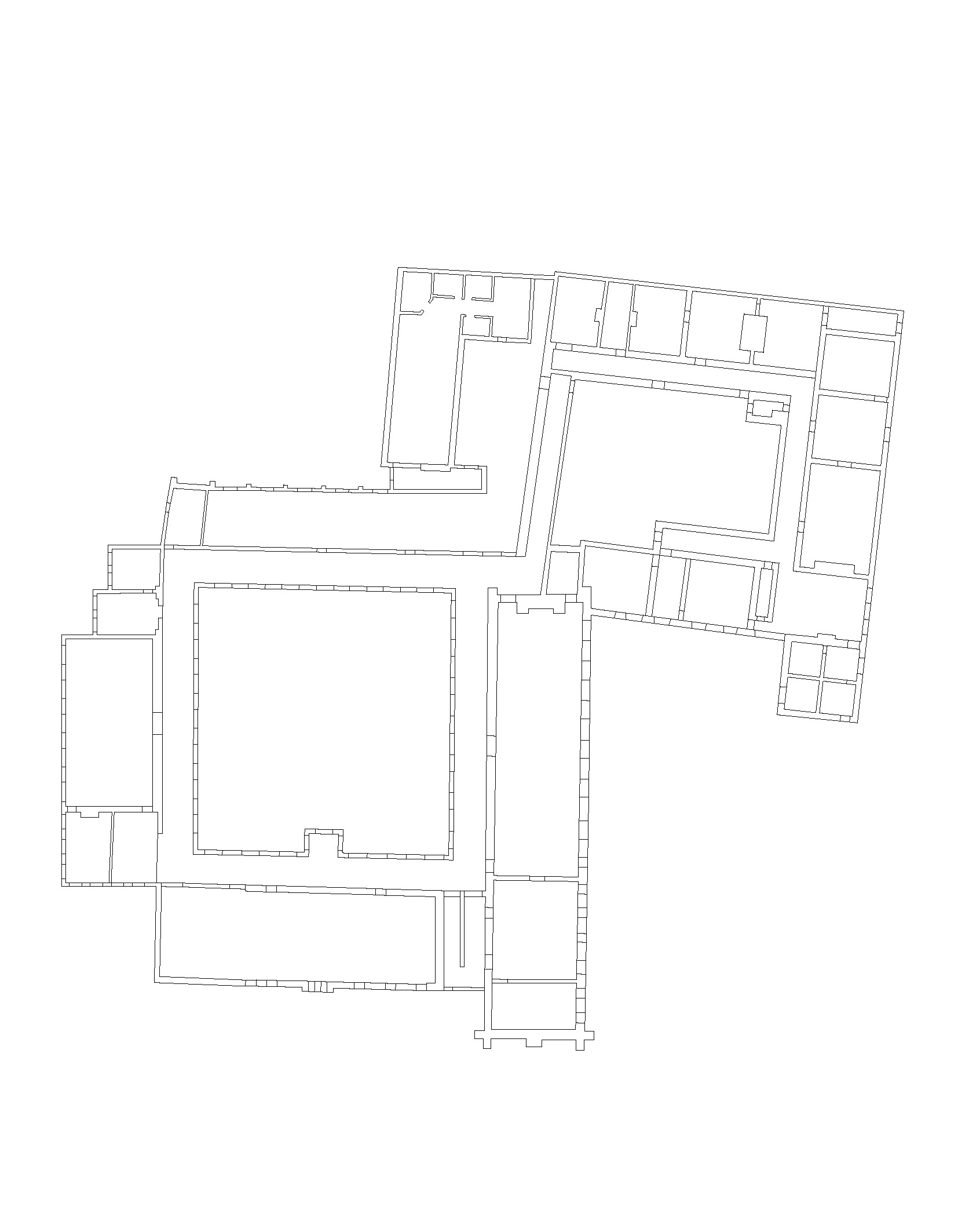

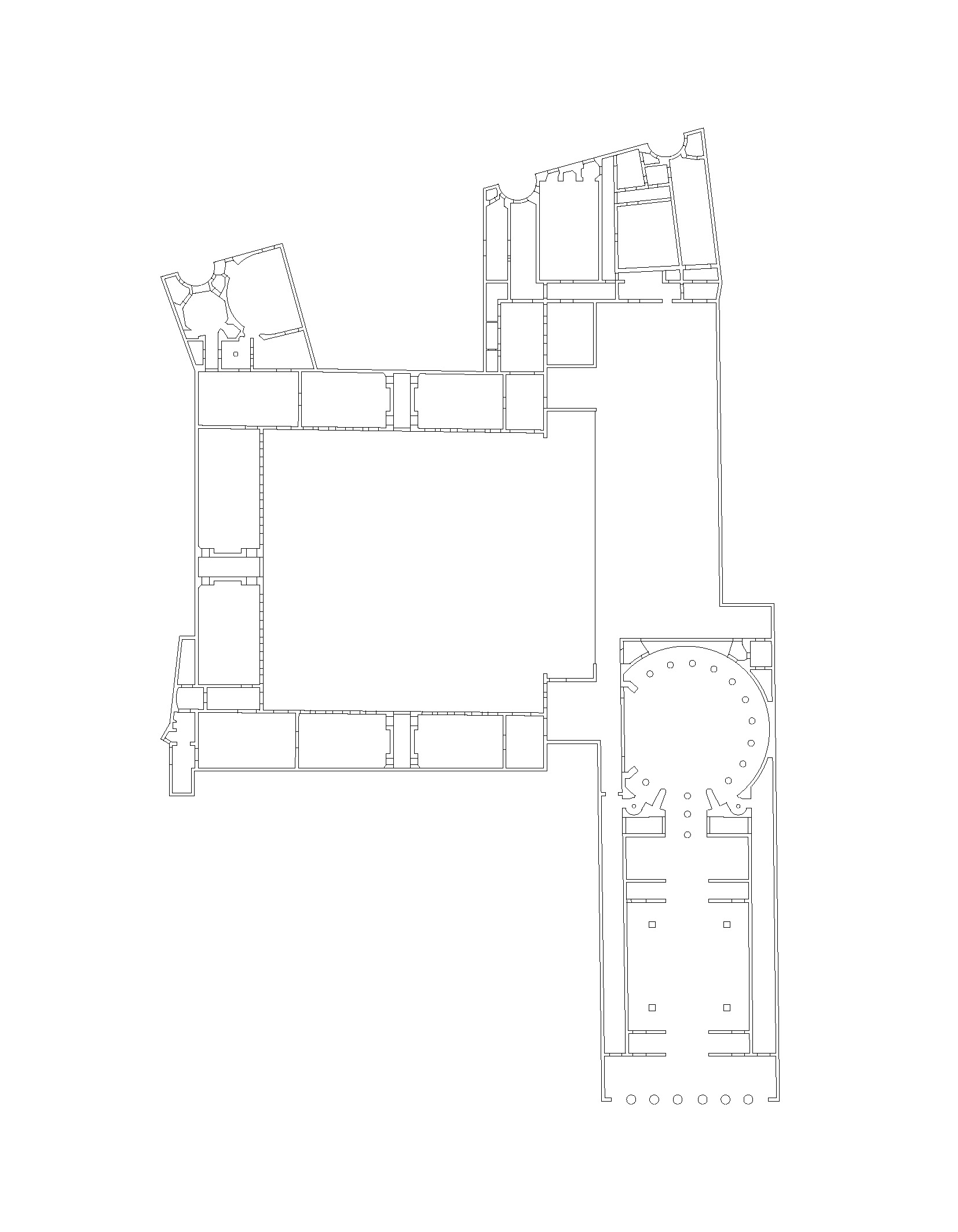

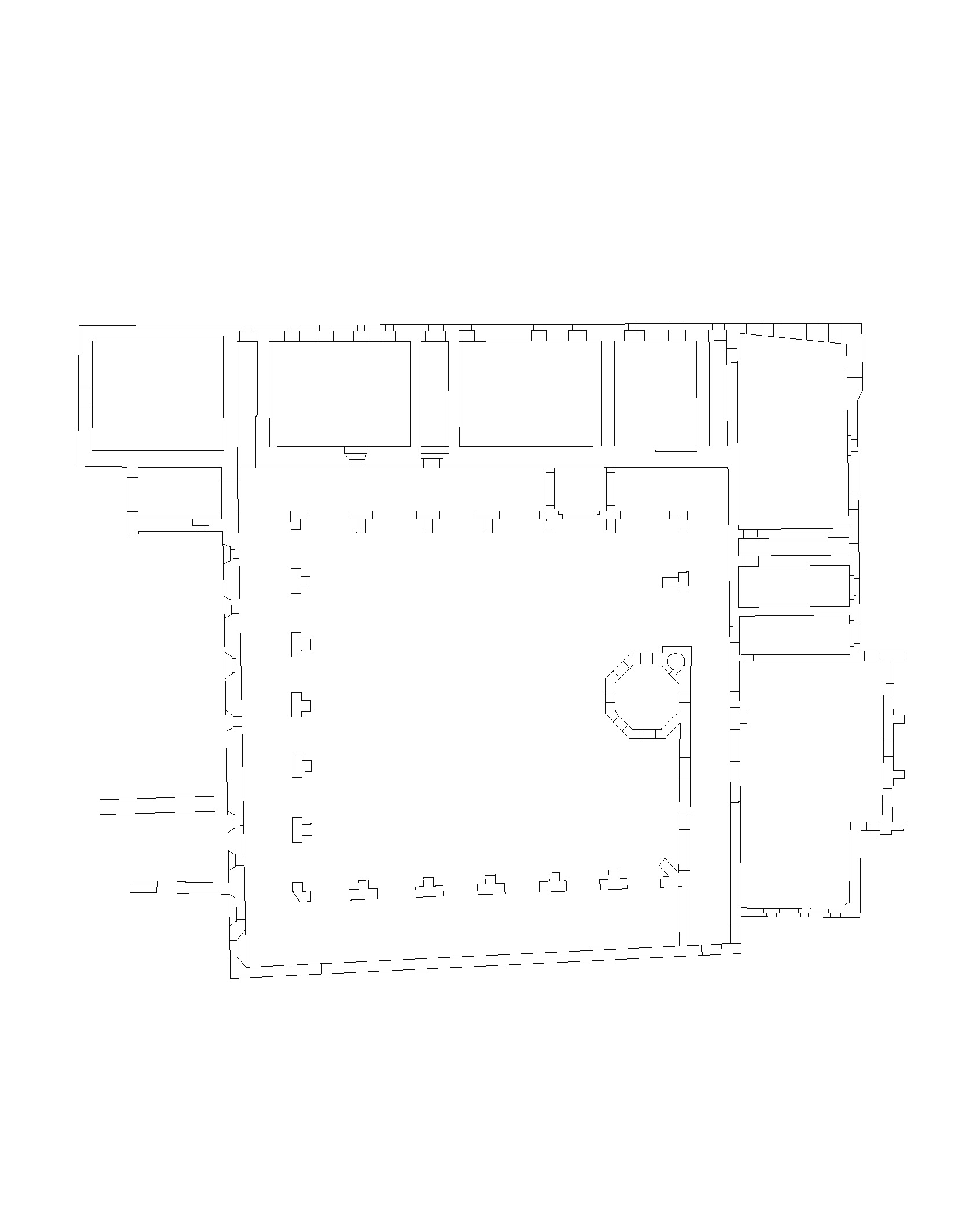

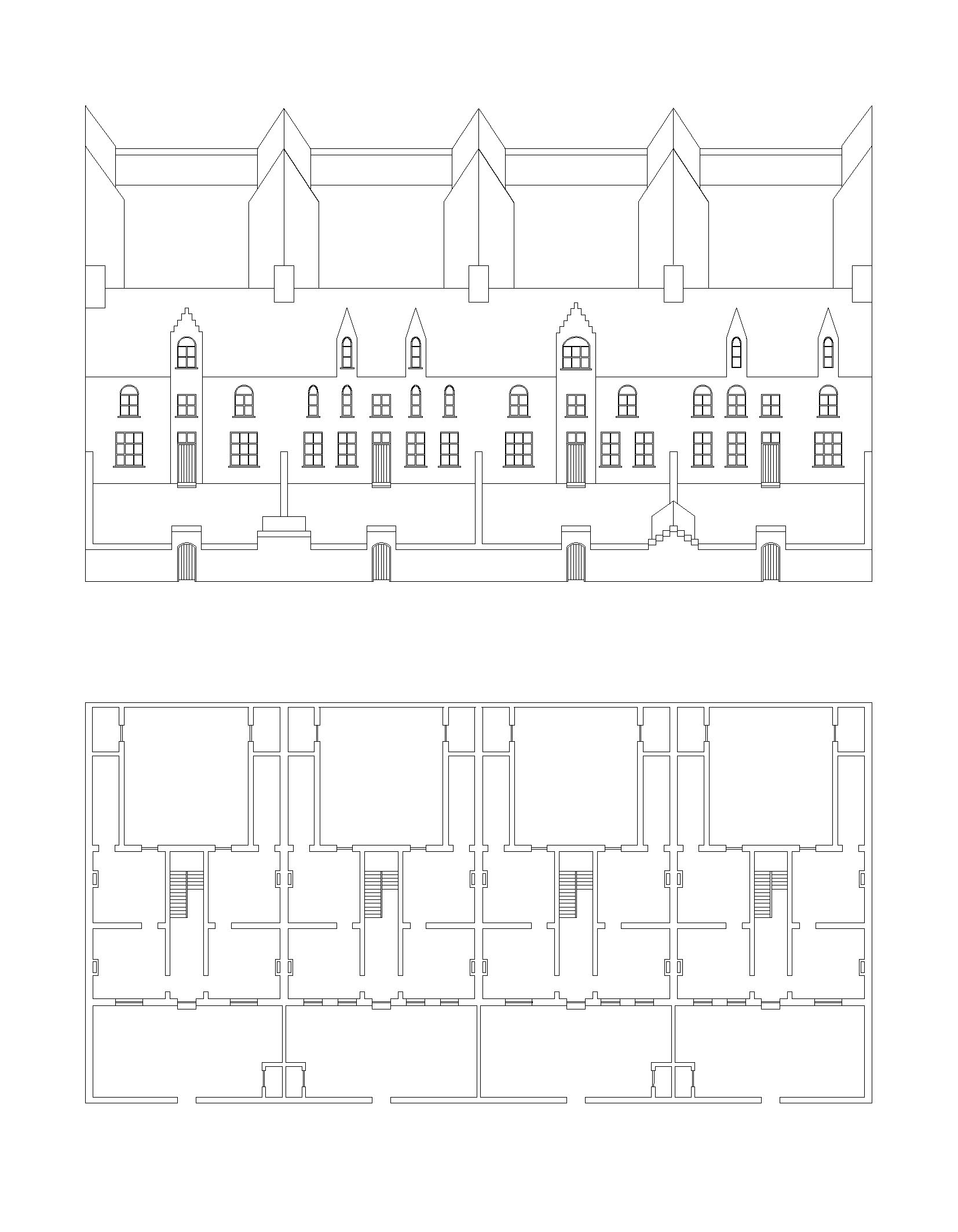

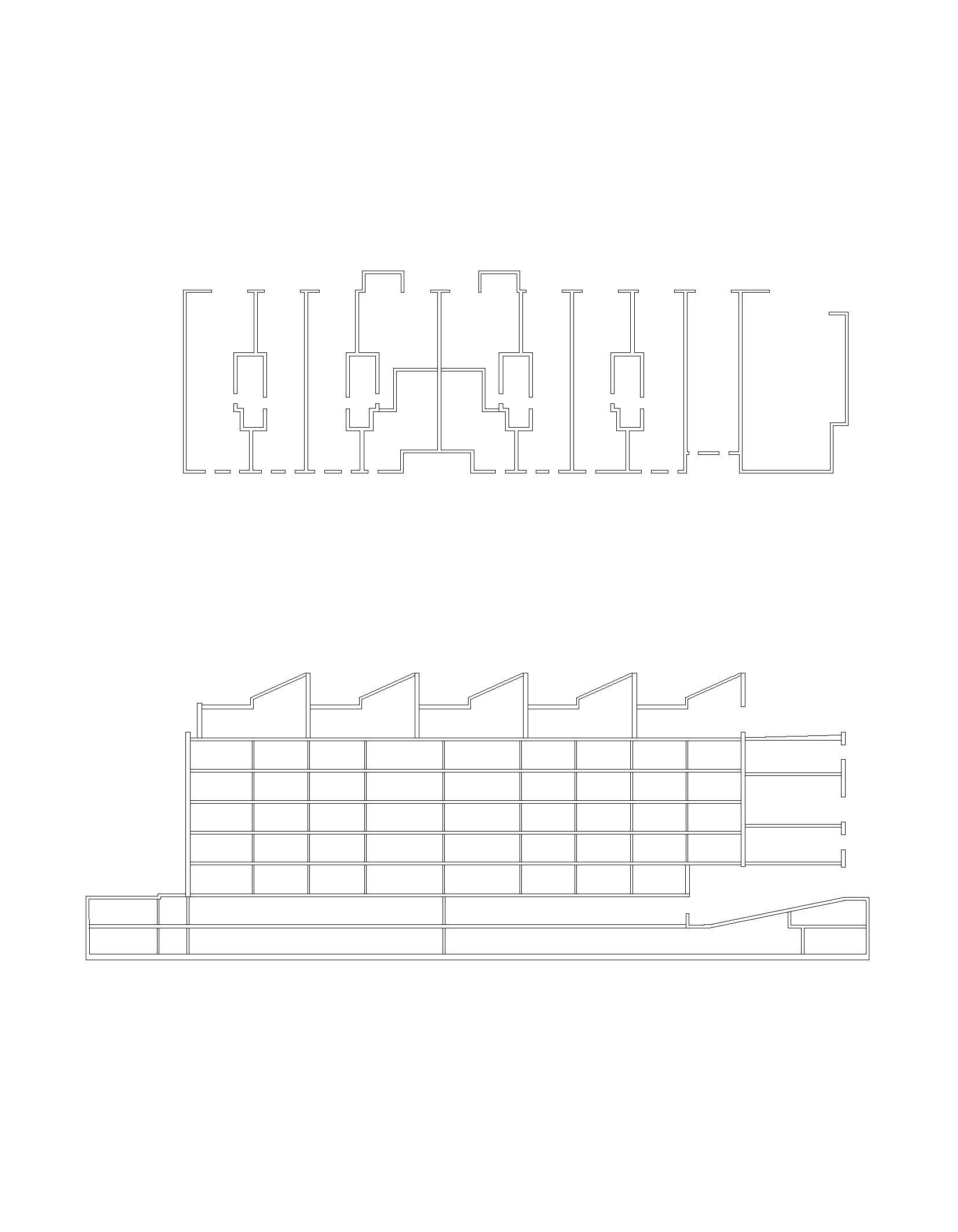

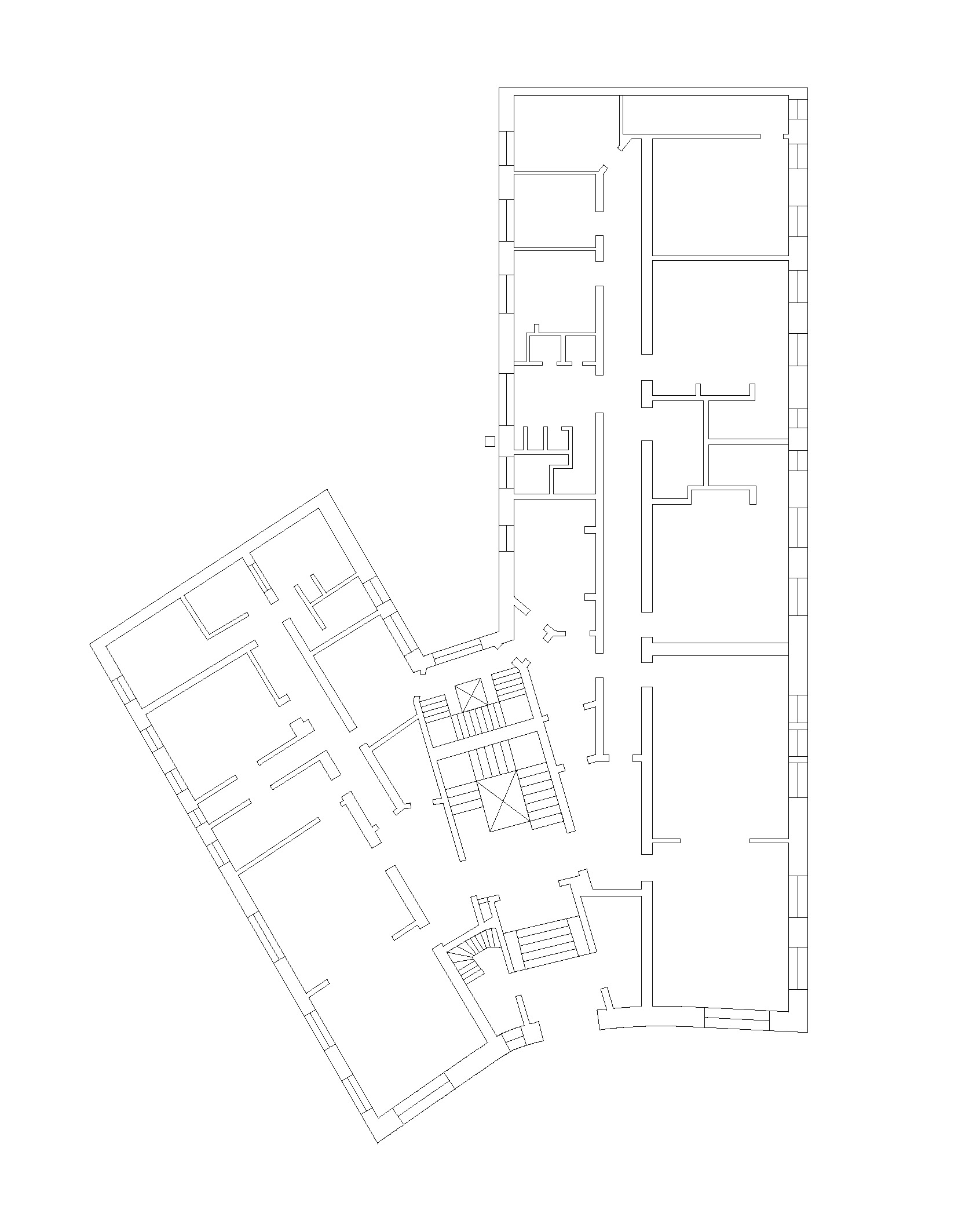

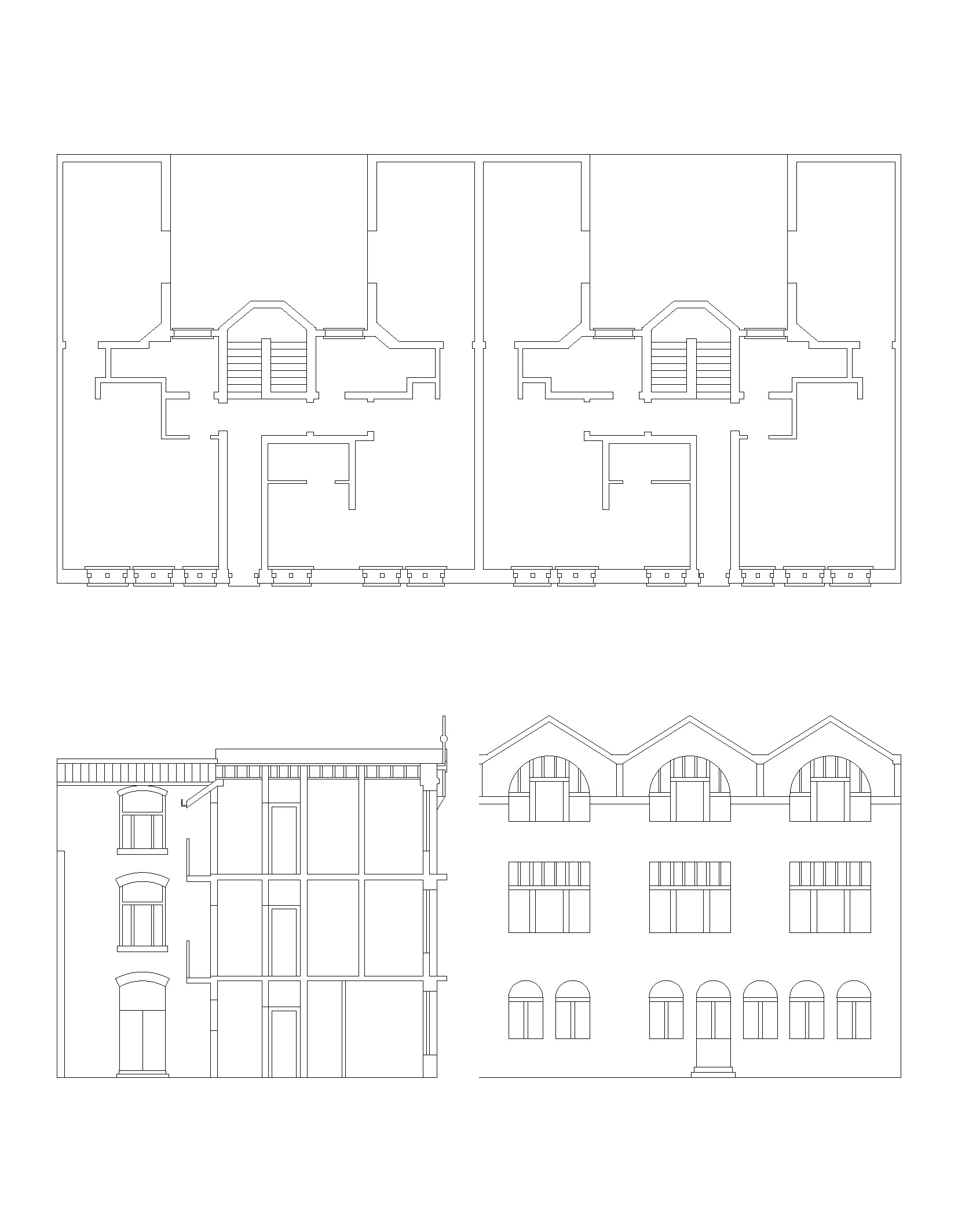

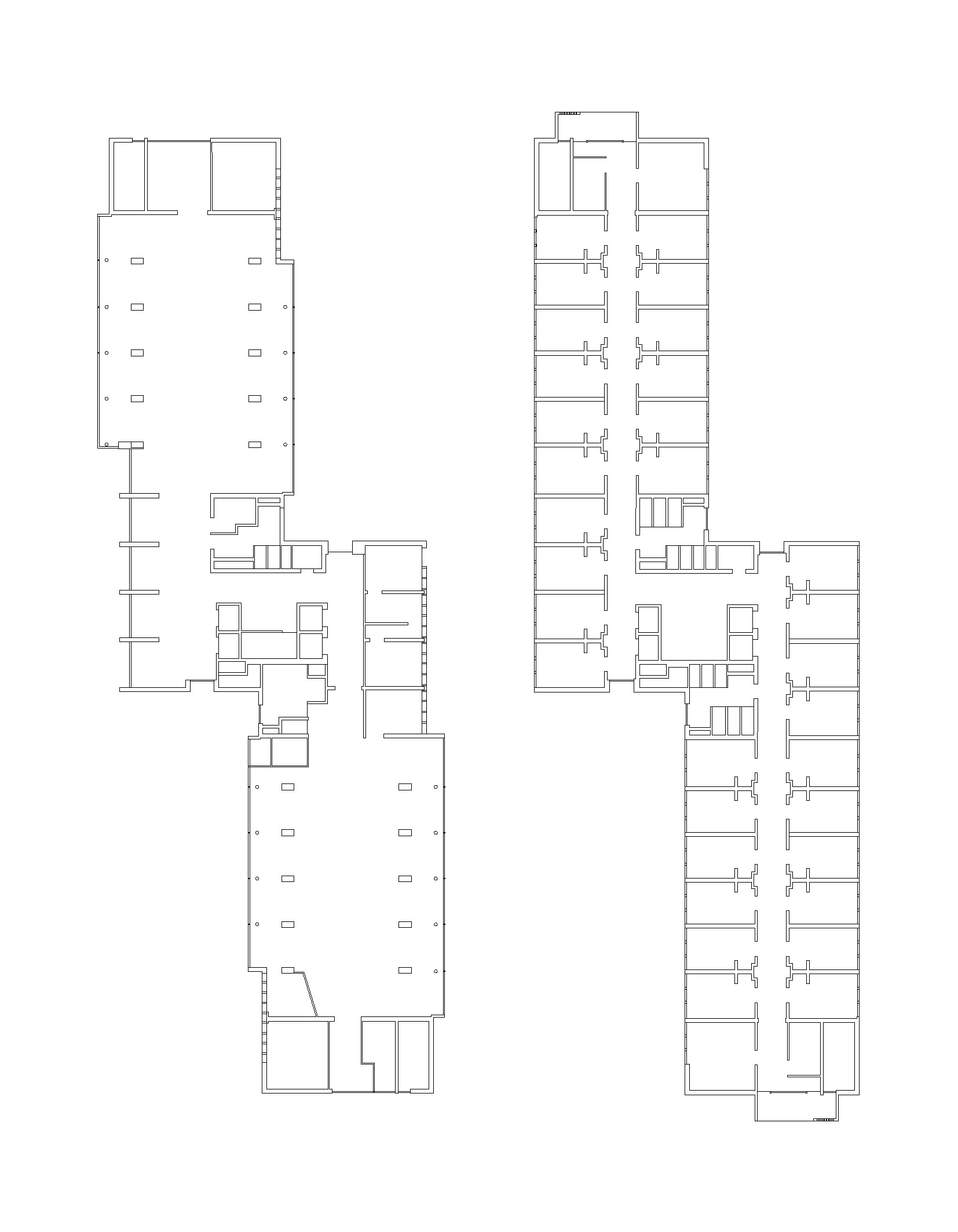

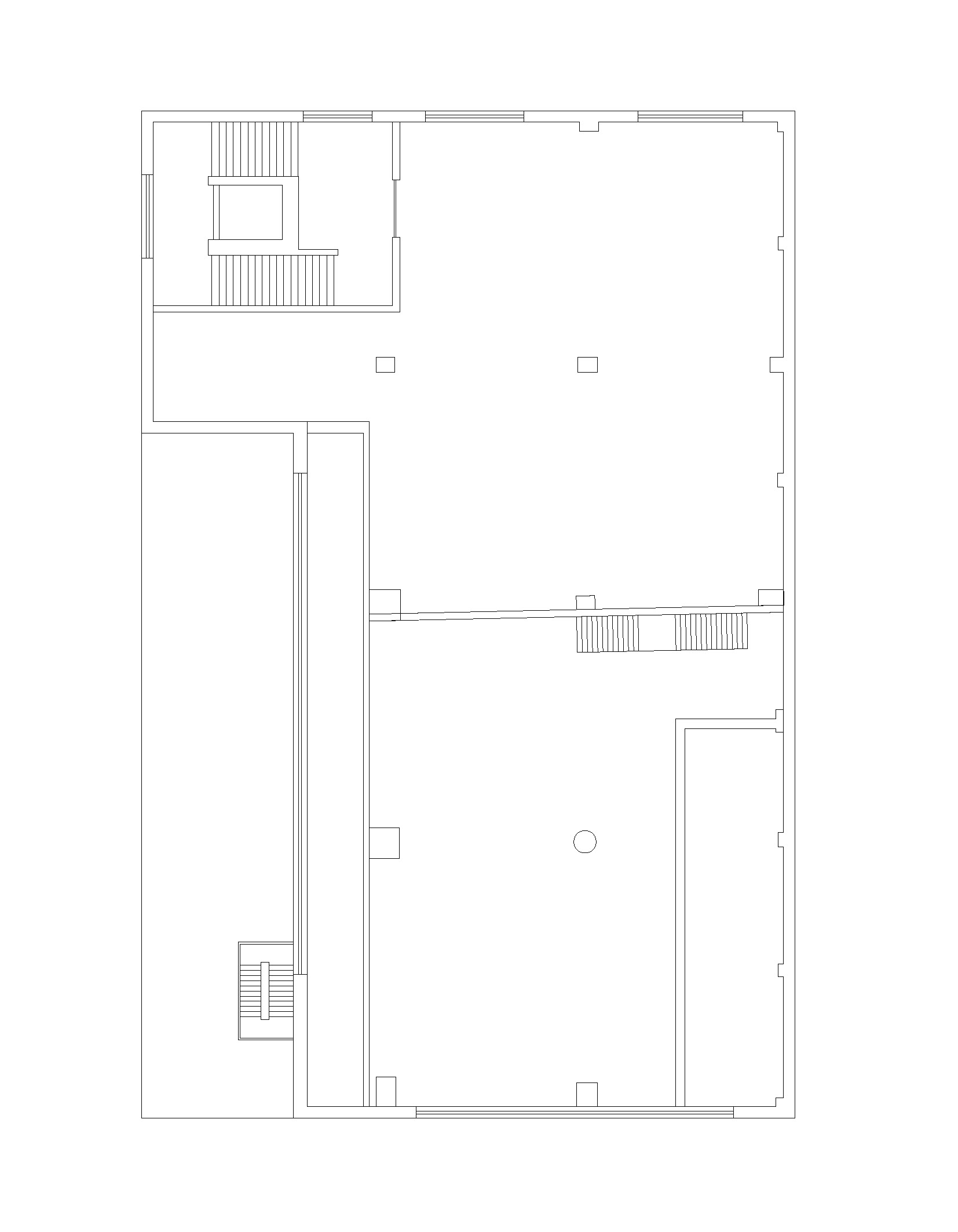

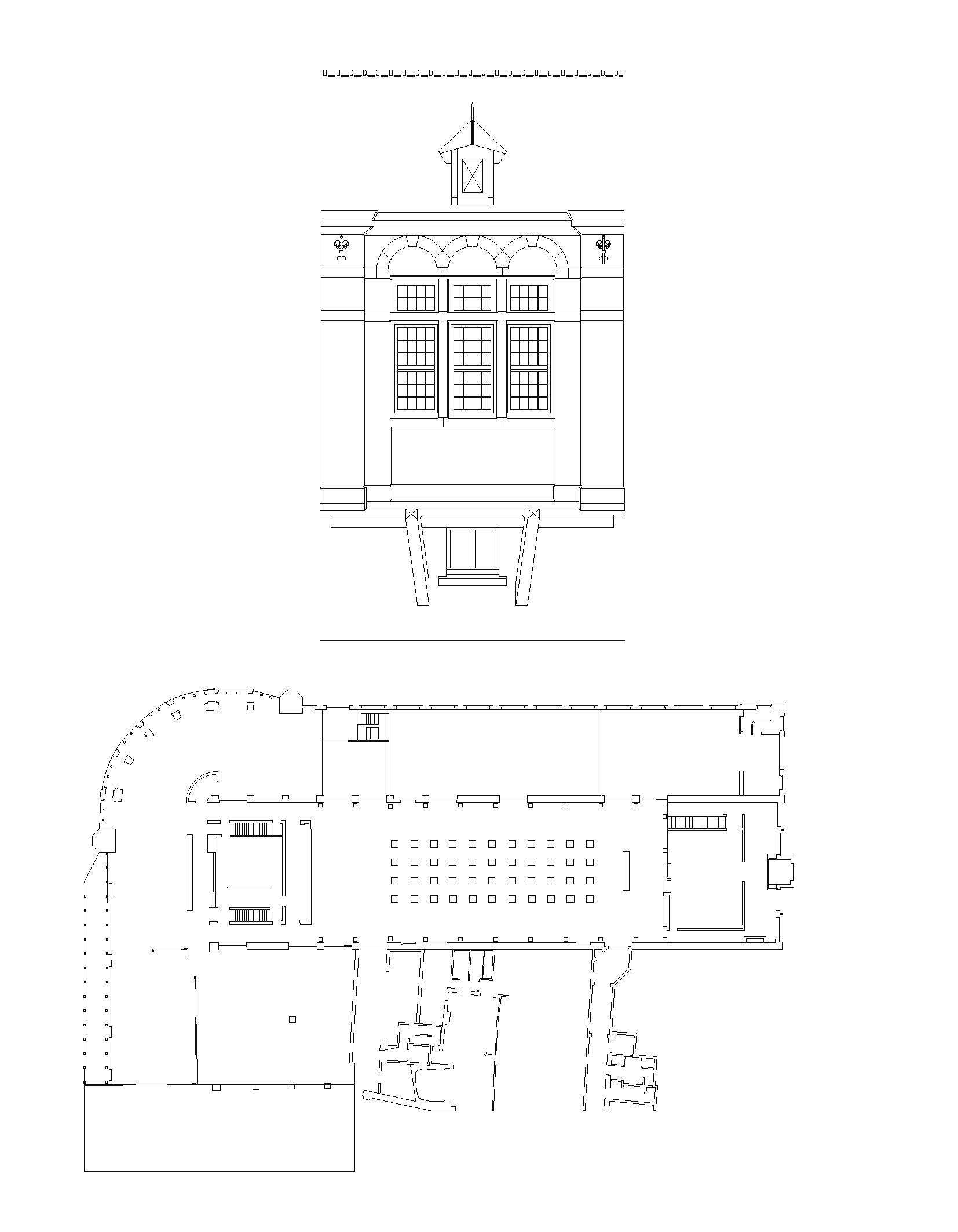

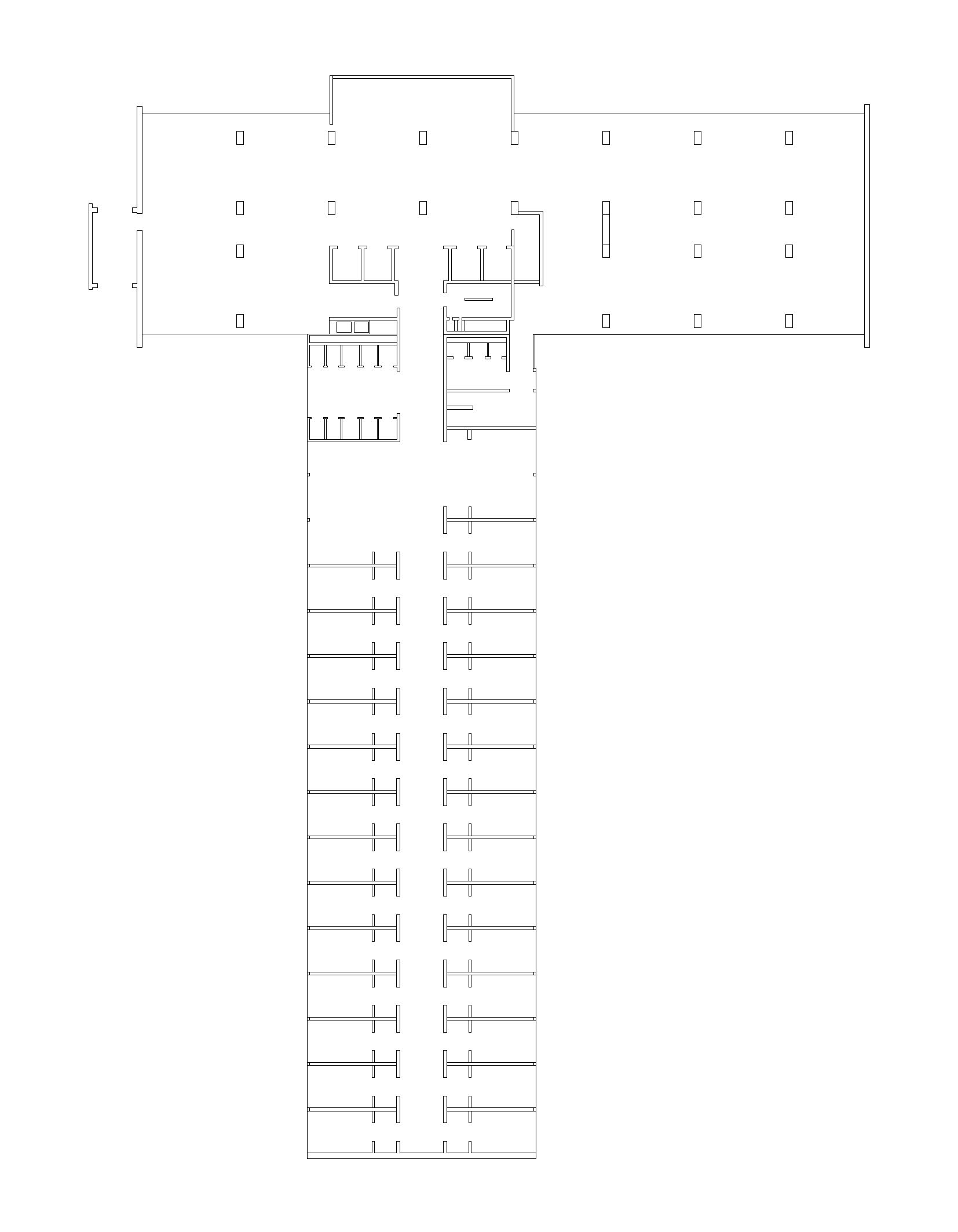

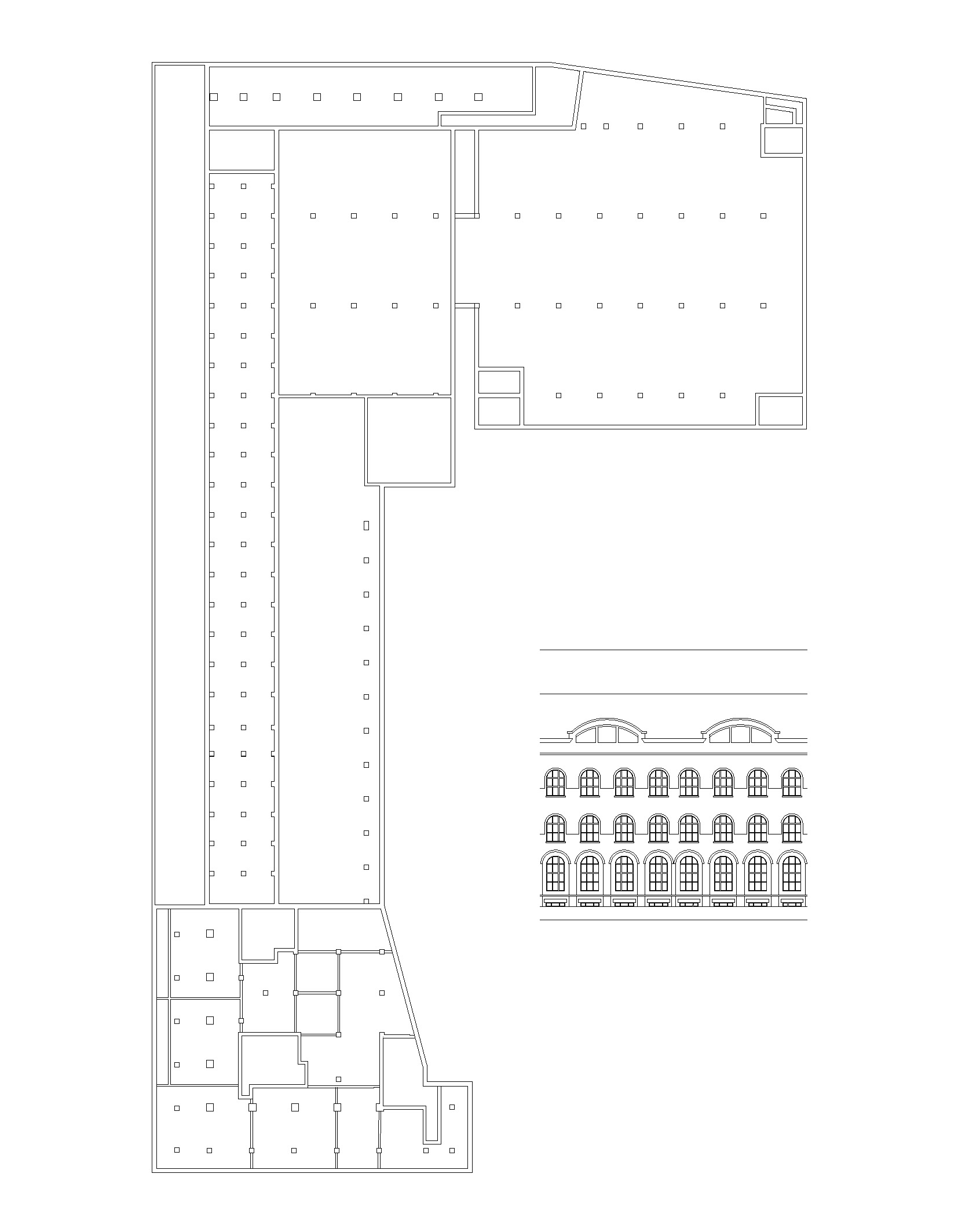

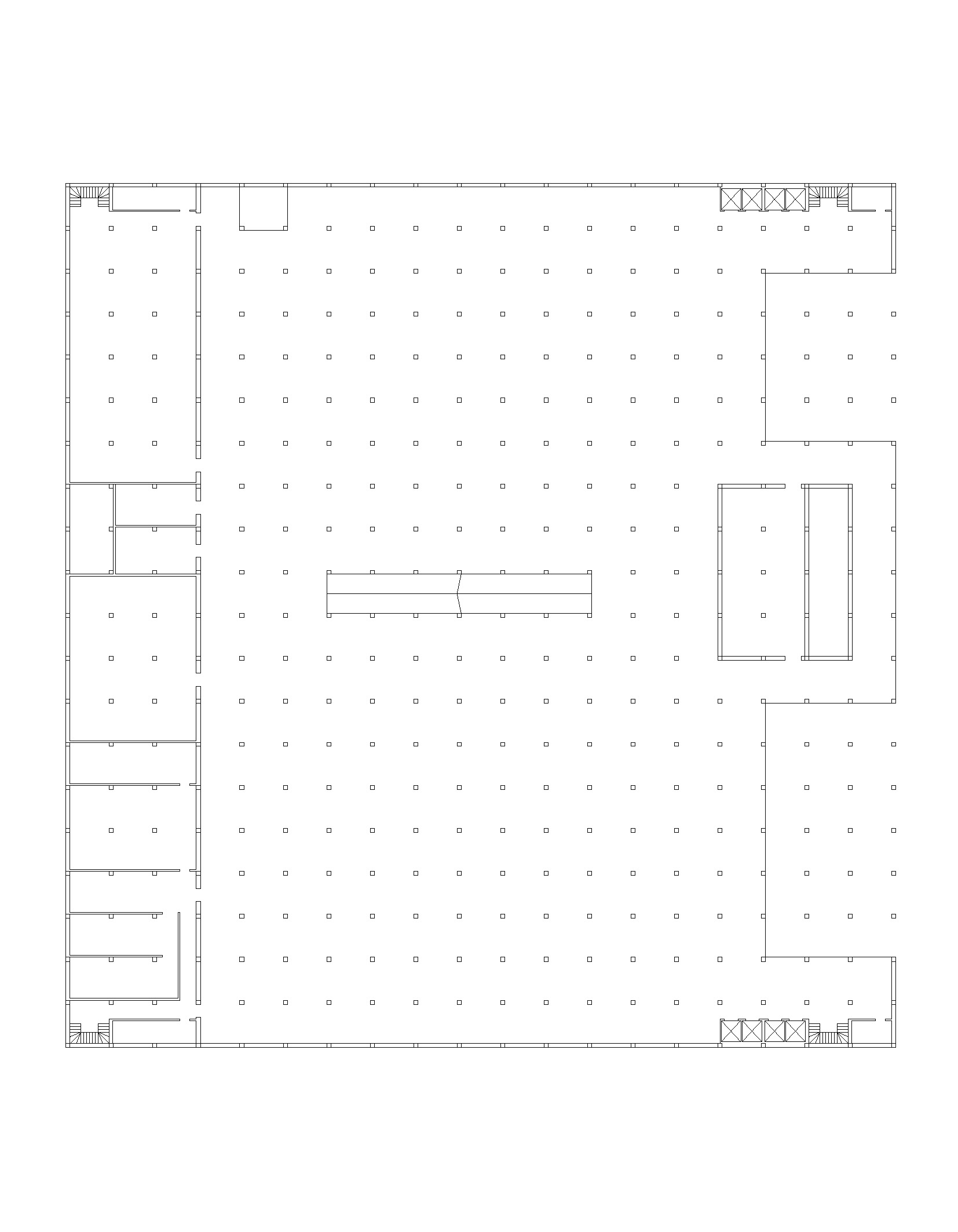

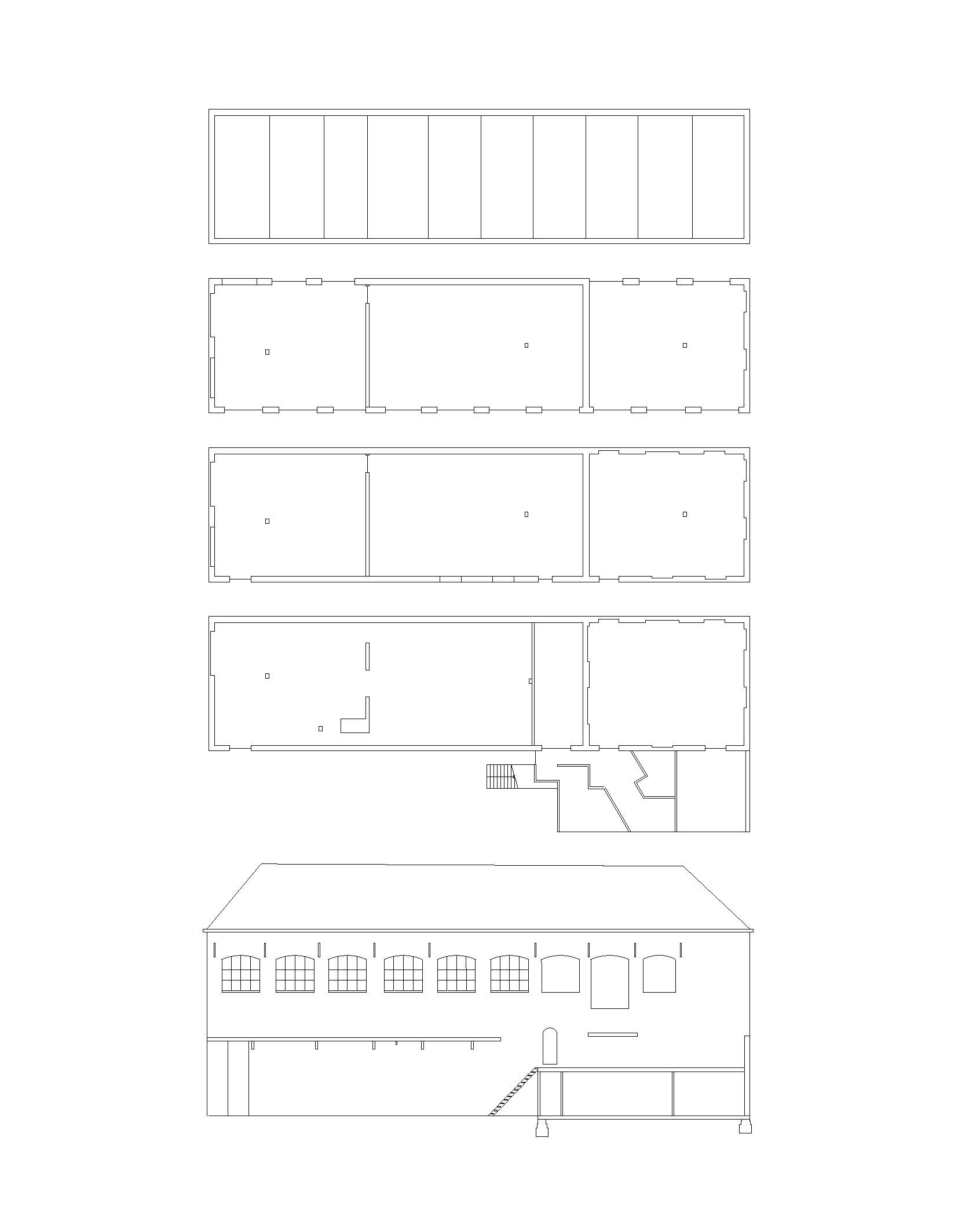

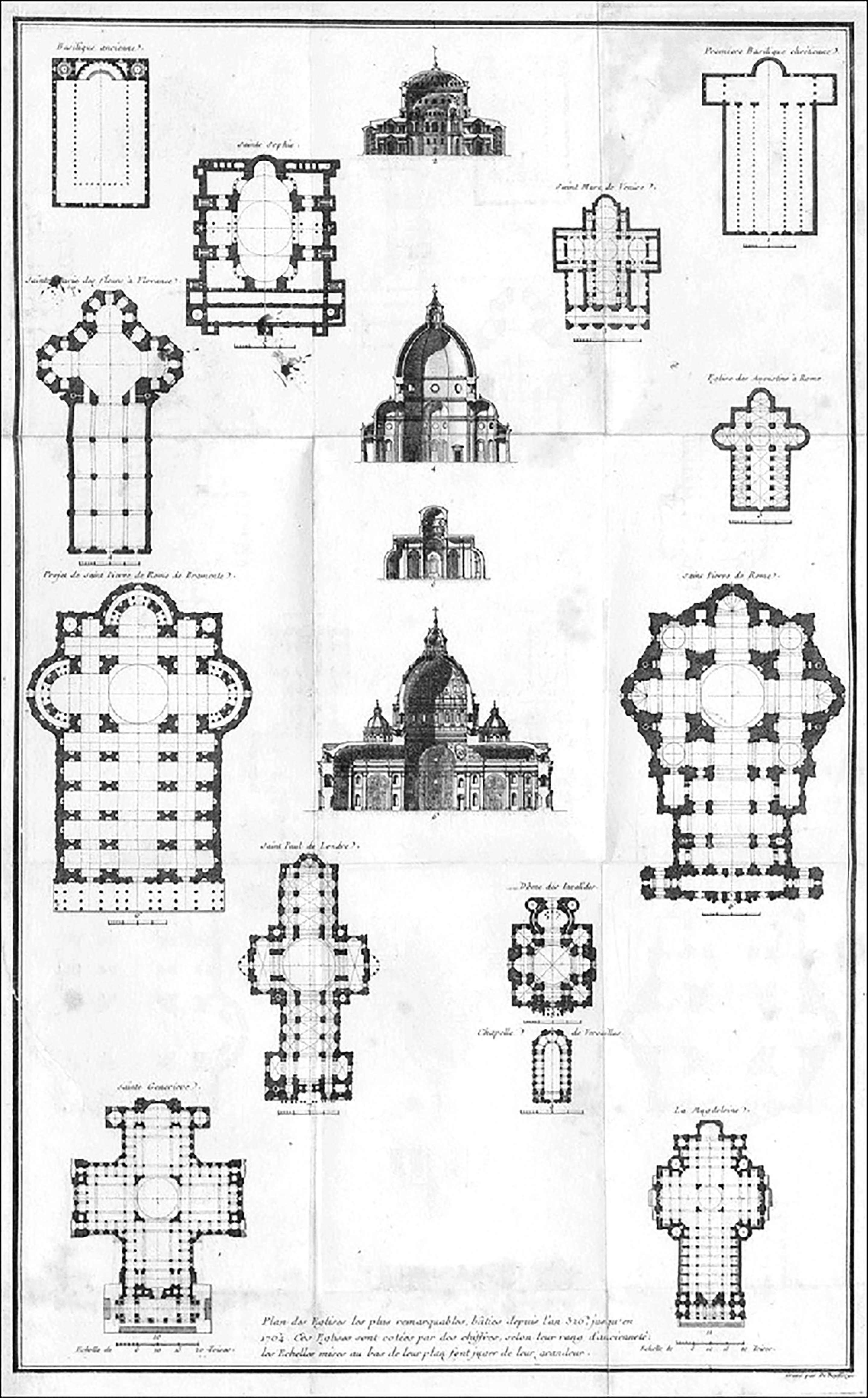

In the 19 century Jean Louis Durand made a catalogue in which he organized the existing buildings according to different ‘genres’. Using simple grid paper he analyzed them and made standardized drawings to develop a system of design using simple modular elements. With this exercise he anticipated contemporary building with industrialized building components. This catalogue of building plans and a collection of constructive ‘elements’ could be combined to conceive any kind of building, public or private. After modernism in which the use of types degraded to stereotype typologies were picked up again by among others Giorgio Grassi, O.M. Ungers and Aldo Rossi in his work ‘the Architecture of the city’.

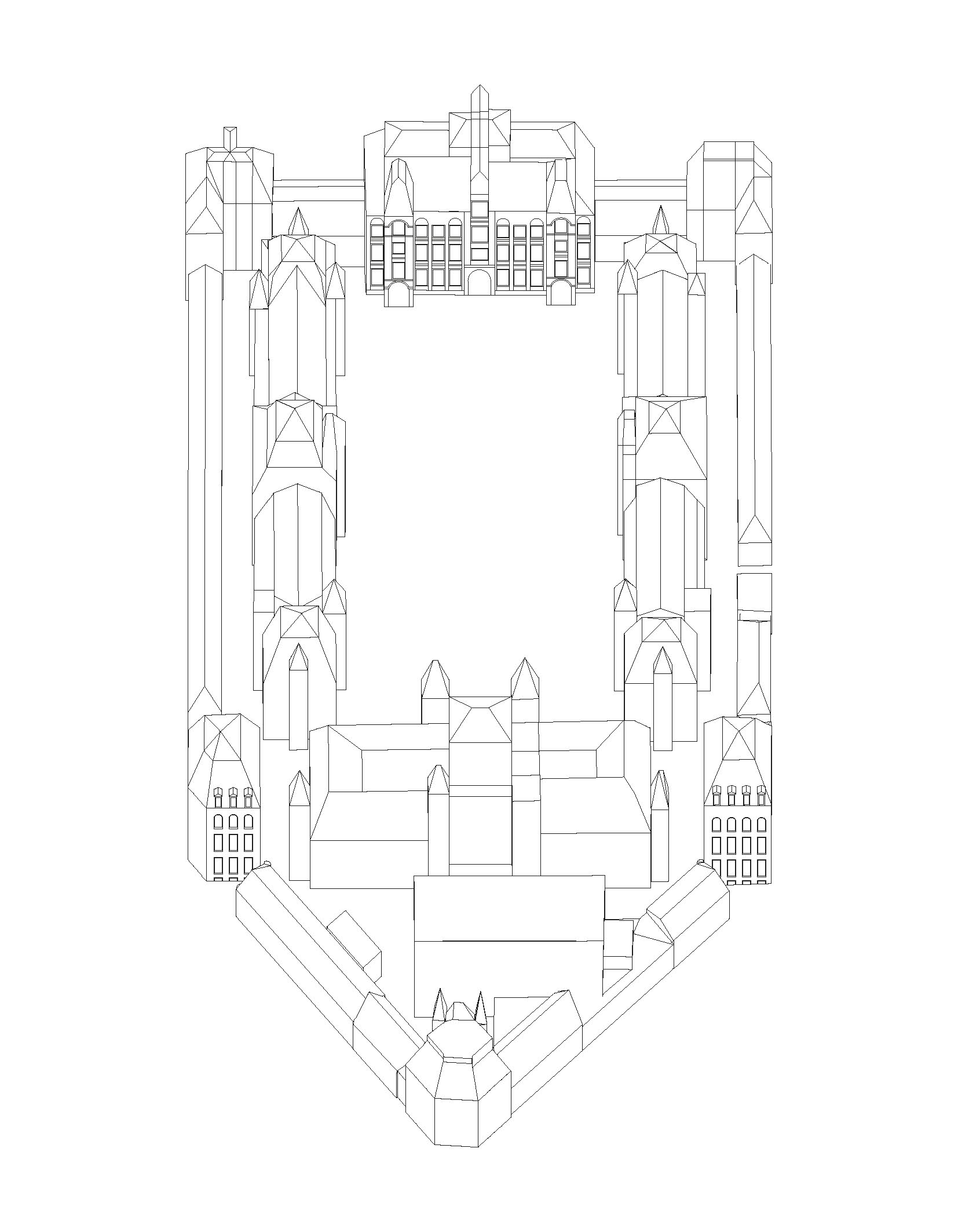

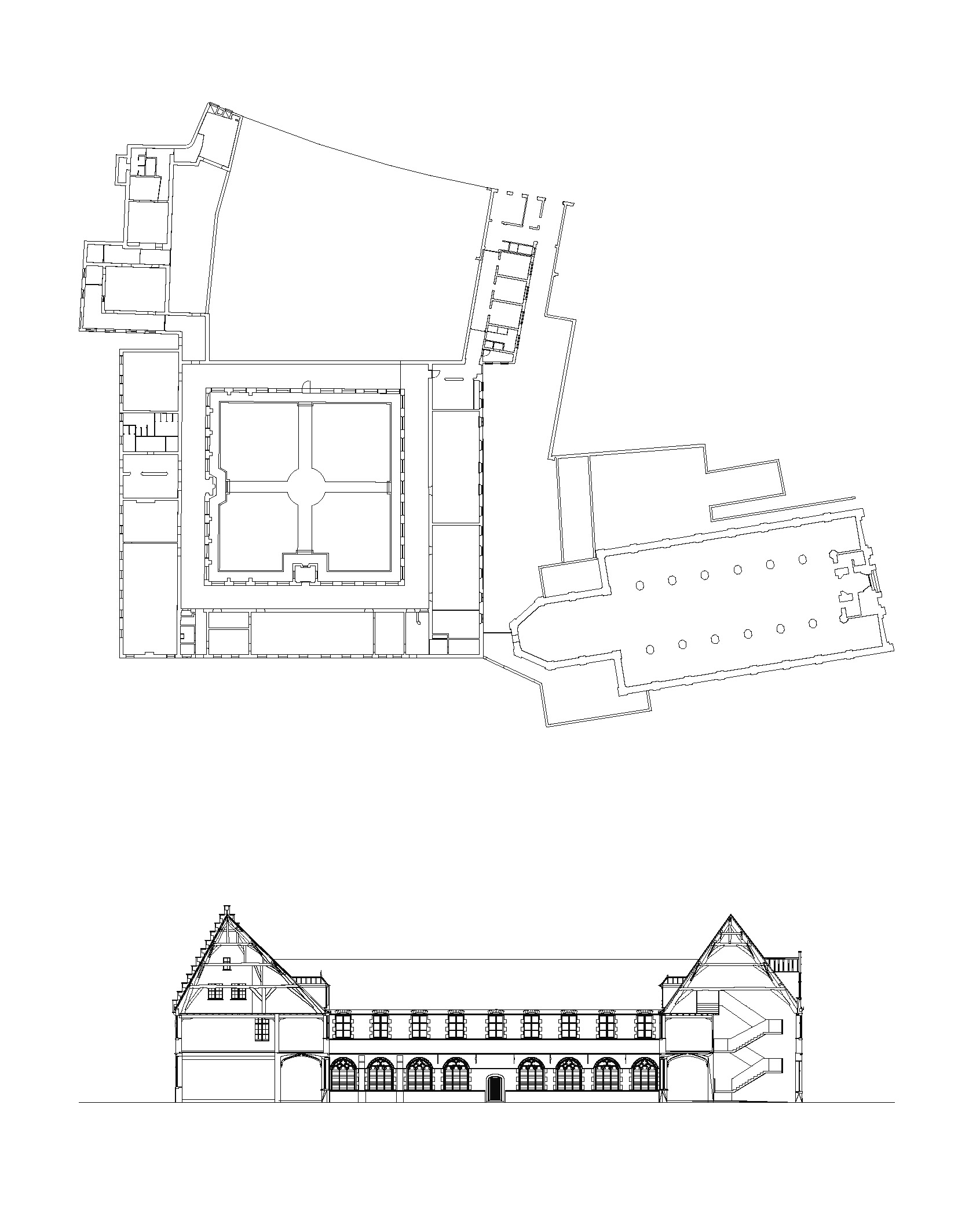

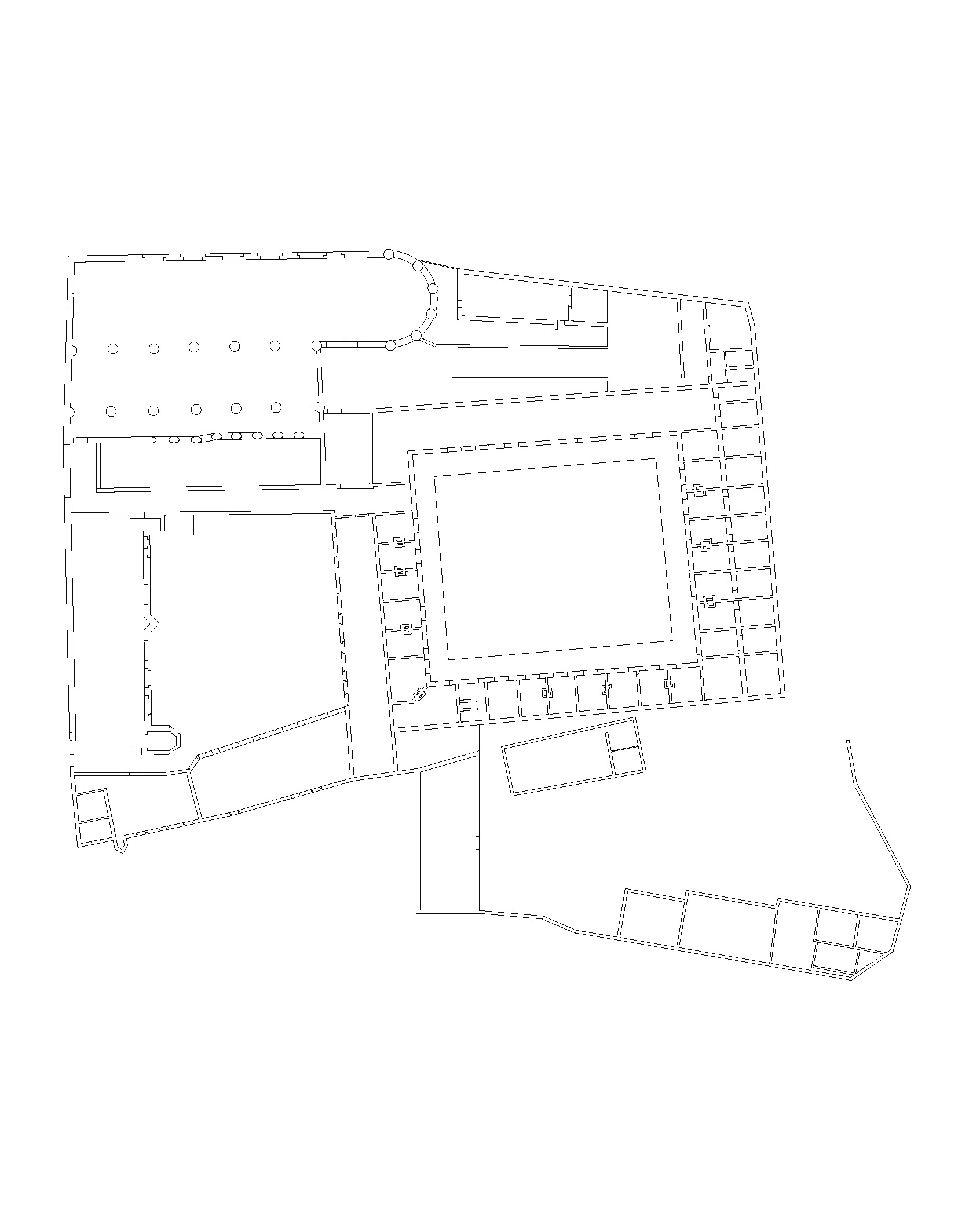

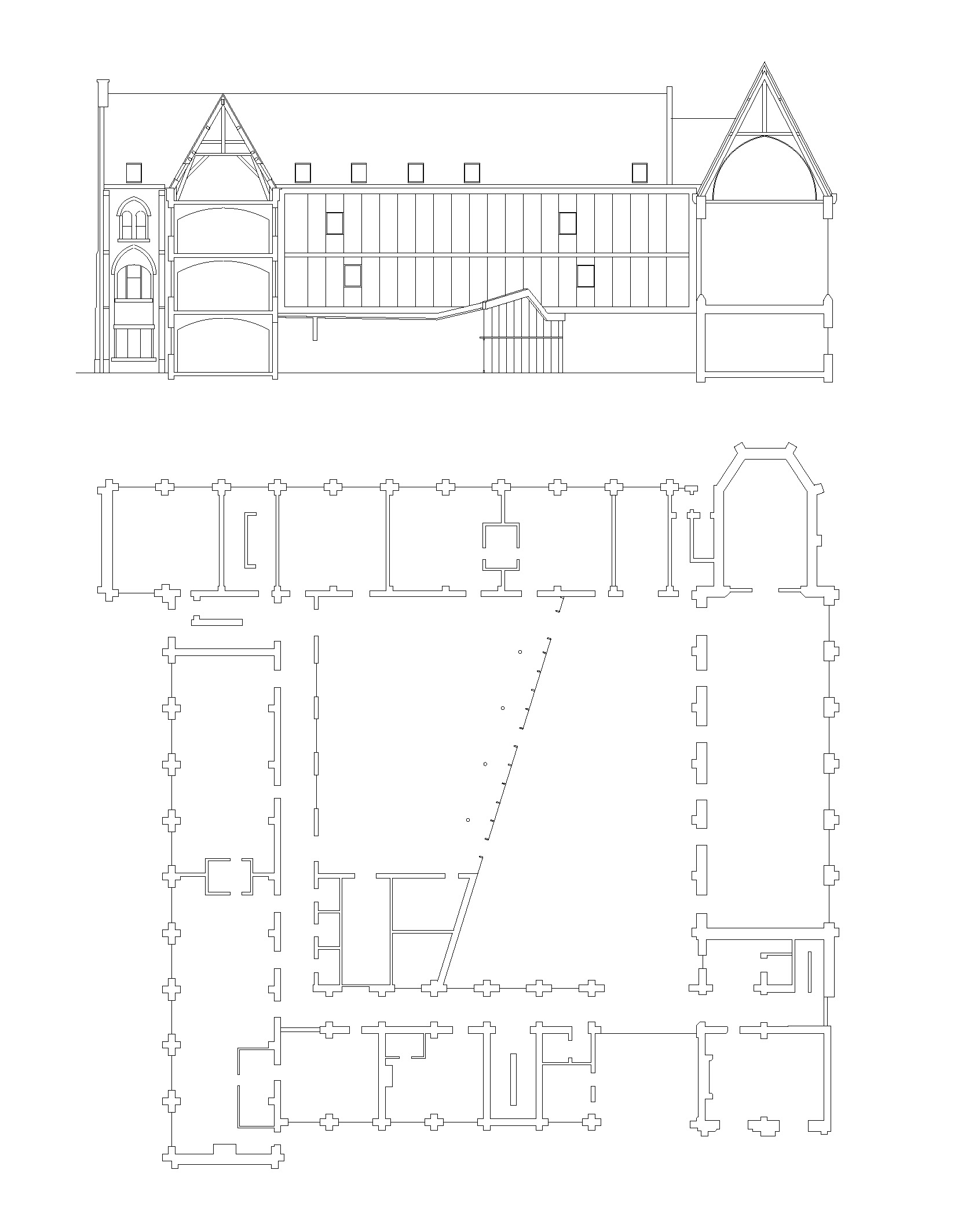

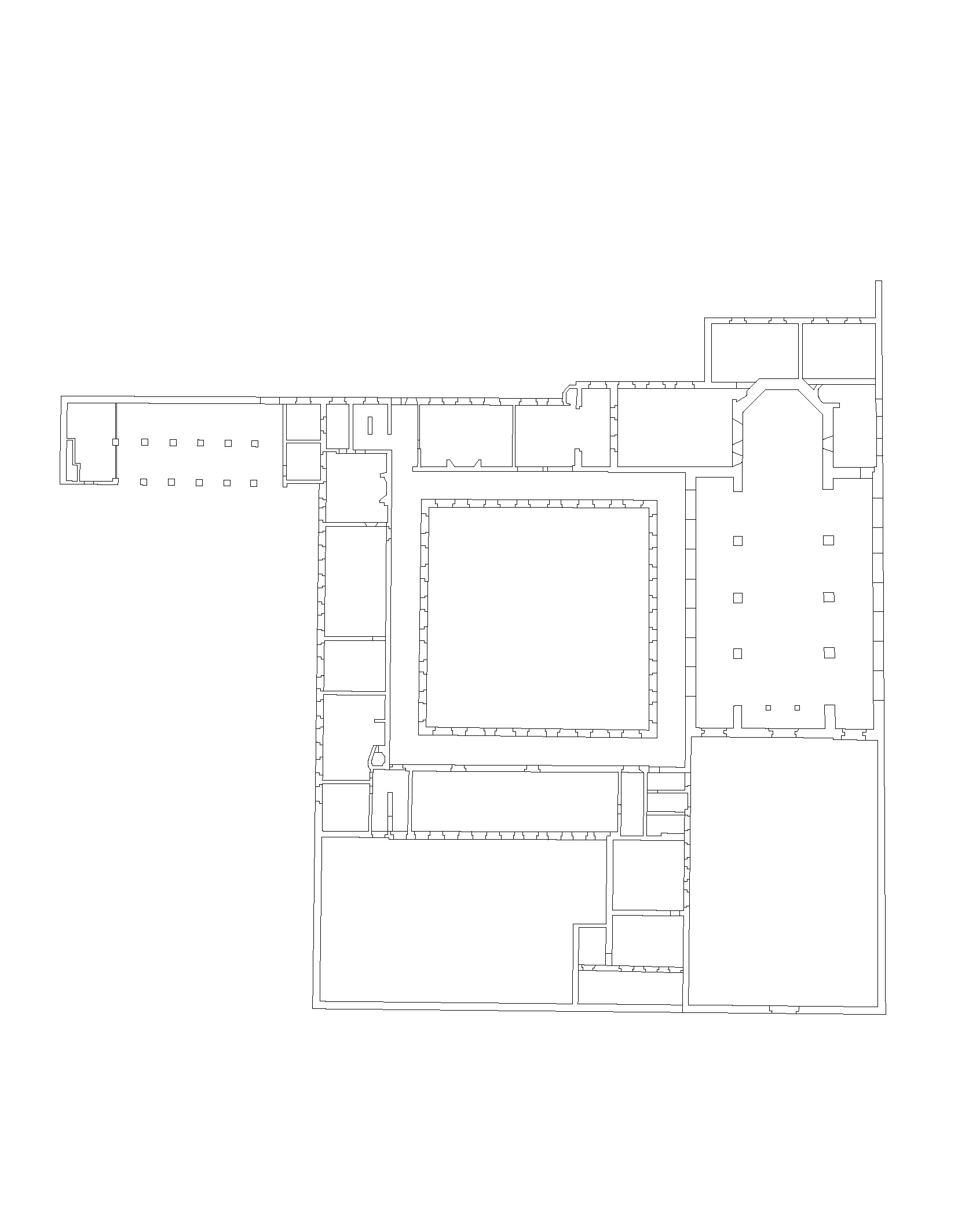

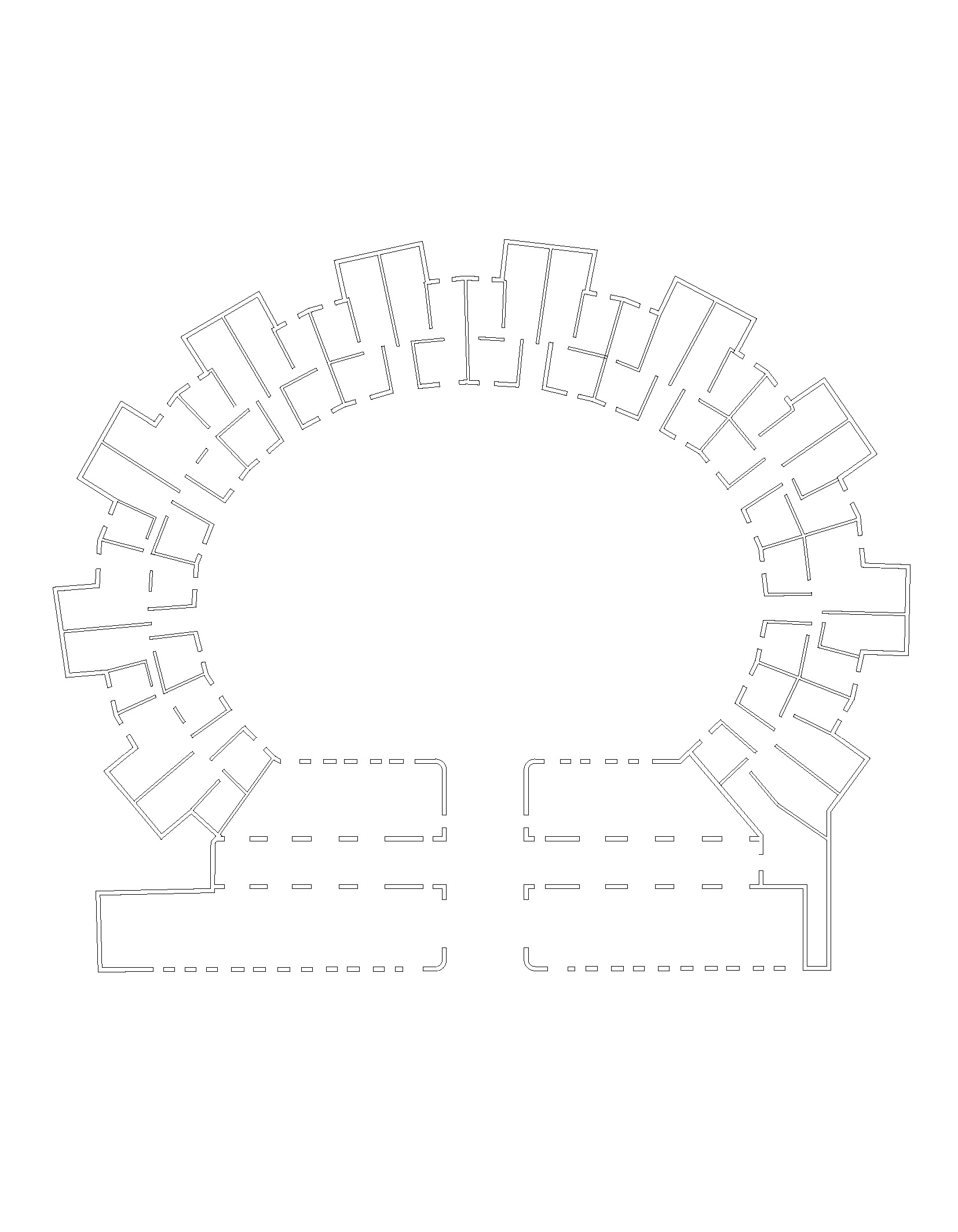

Julien-David Le Roy, ‘Plan des églises les plus remarquables, baties depuis l’an 326 jusqu’en 1764’. From Le Roy (1764).

These types make up a large part of historical european cities and have proven to be very suitable for re-use. There is an interesting interaction between typology and structure. The building system has influenced the type which had to accommodate the widest range of programmatic diversity. It is precisely this characteristic that makes it interesting to study these types to help us today in our search for a resilient structure. The debate has largely evaporated in the contemporary architectural debate but is only recently being picked up again.

The aim is not to historicize but to bridge the gap in how to use these examples today and to create the awareness that the construction of the city is not a singular a-historical endeavor.

J.N.L.Durand, Recueil et parallèle des édifices de tout genre, anciens et modernes, 1800. Planche 2

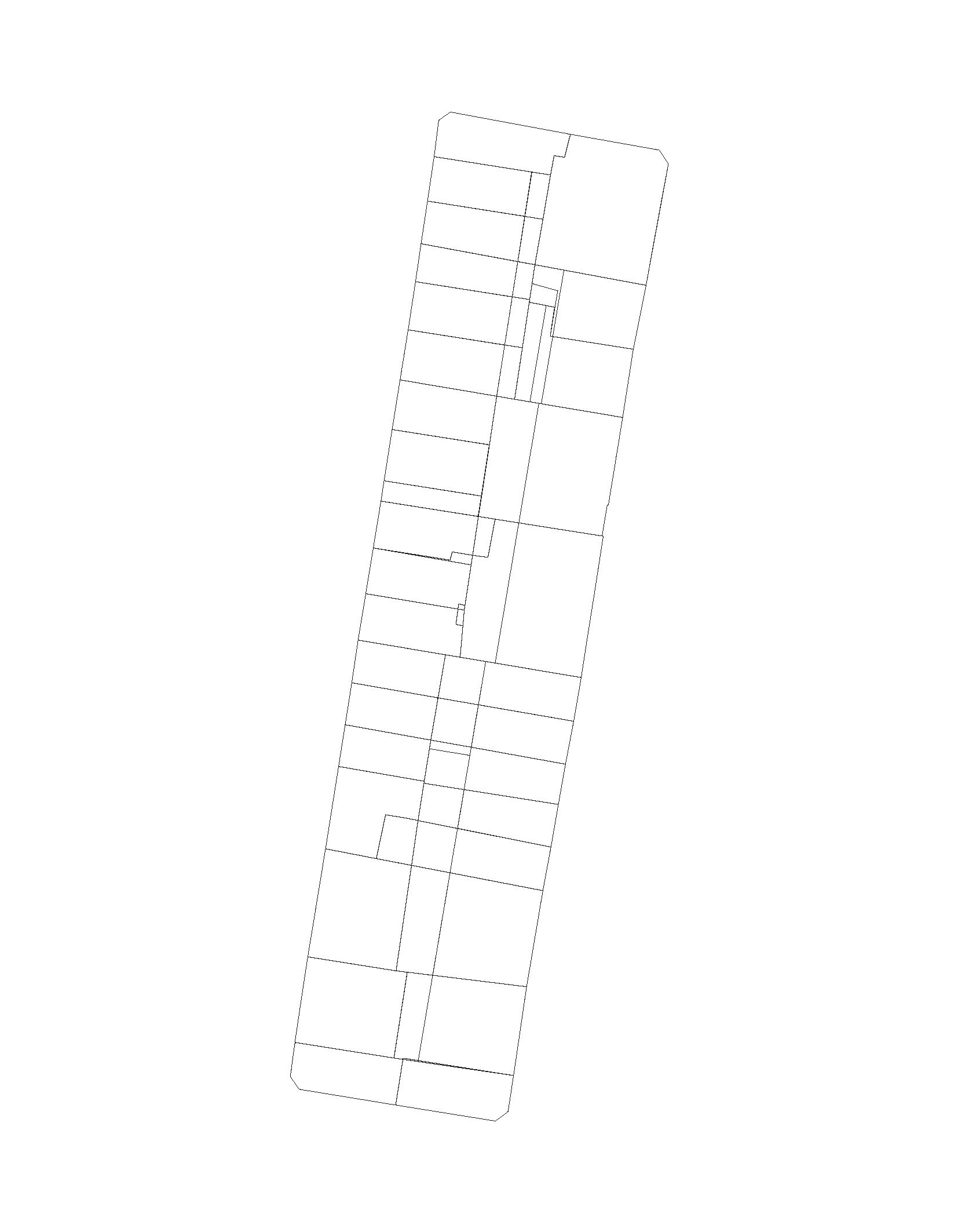

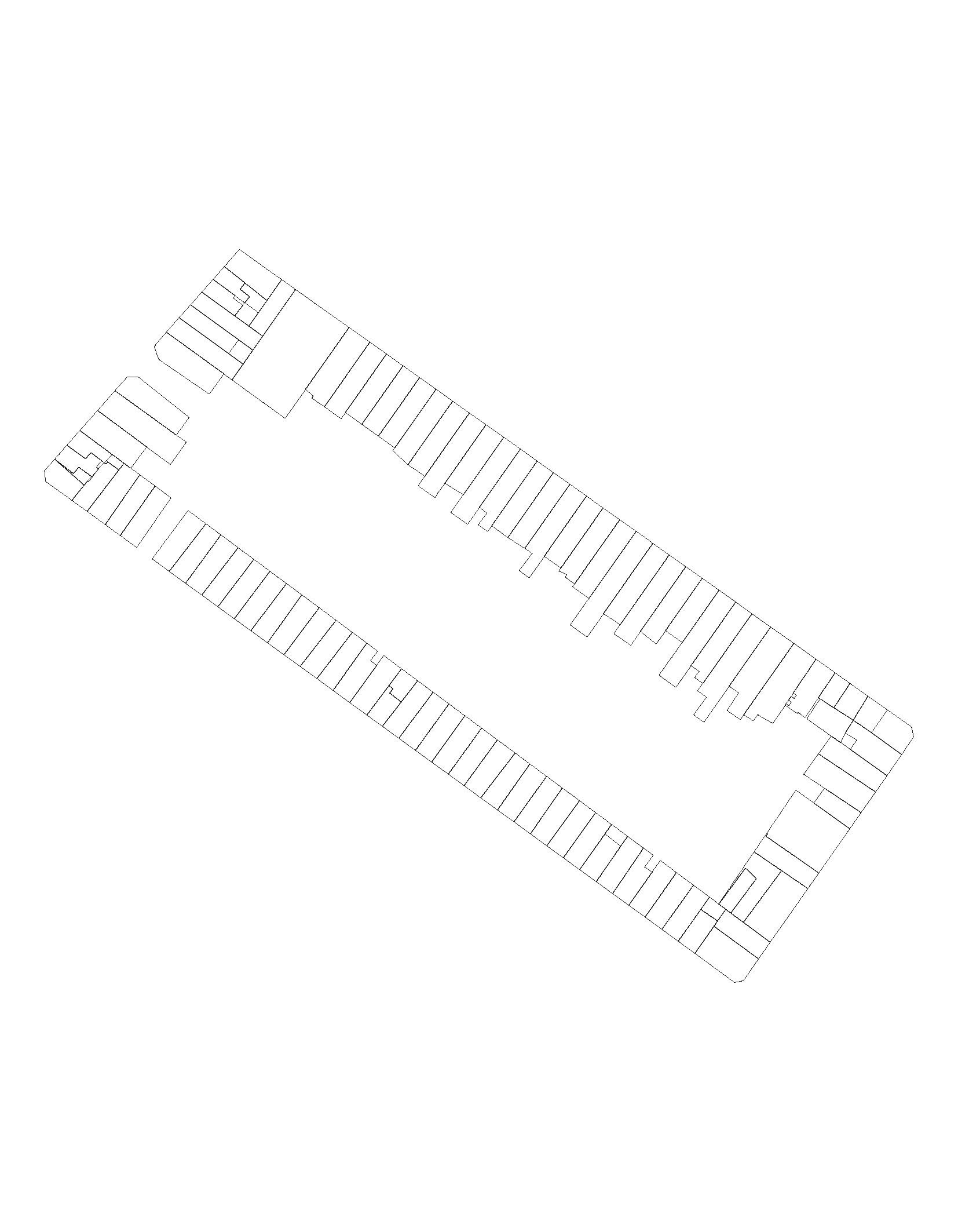

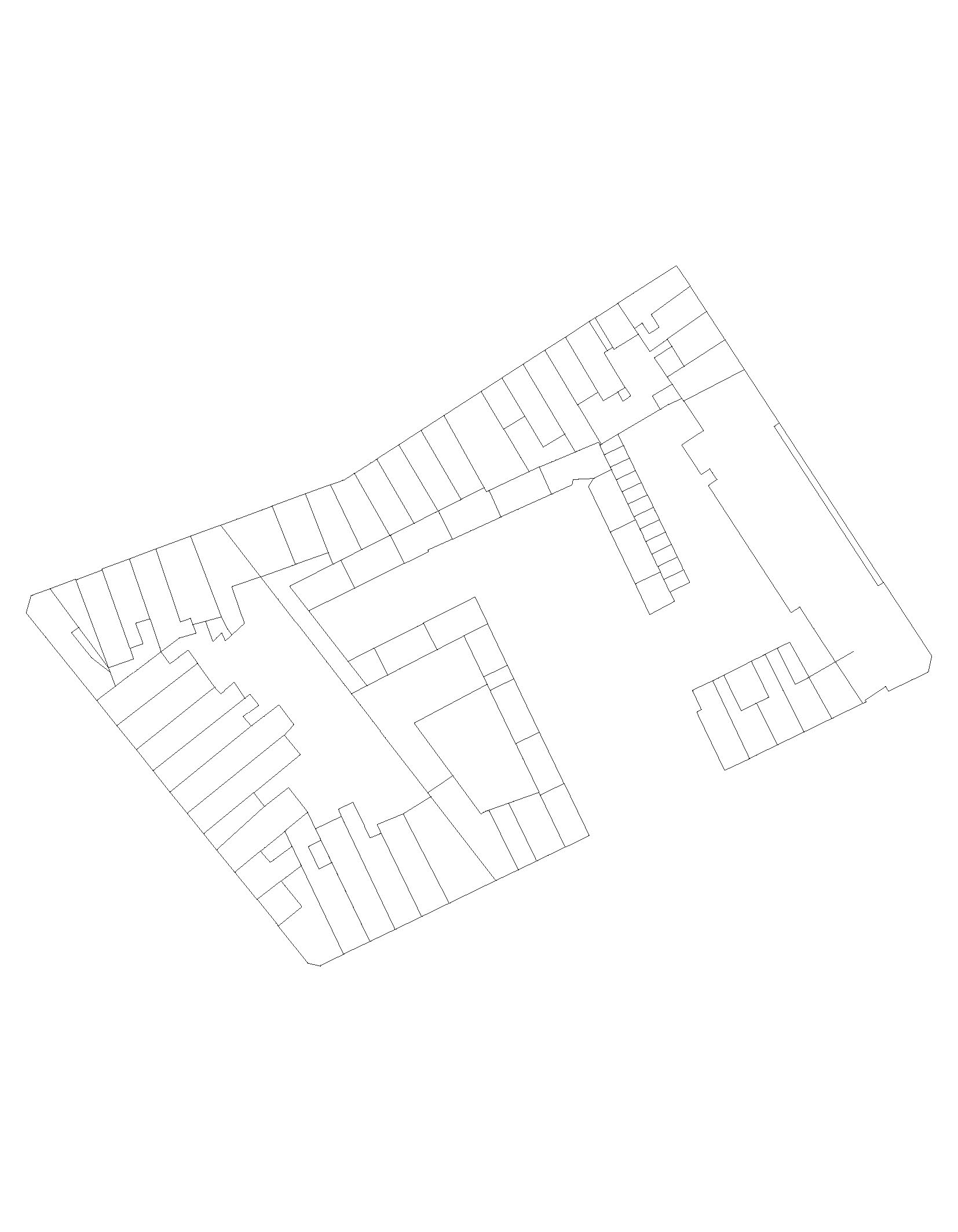

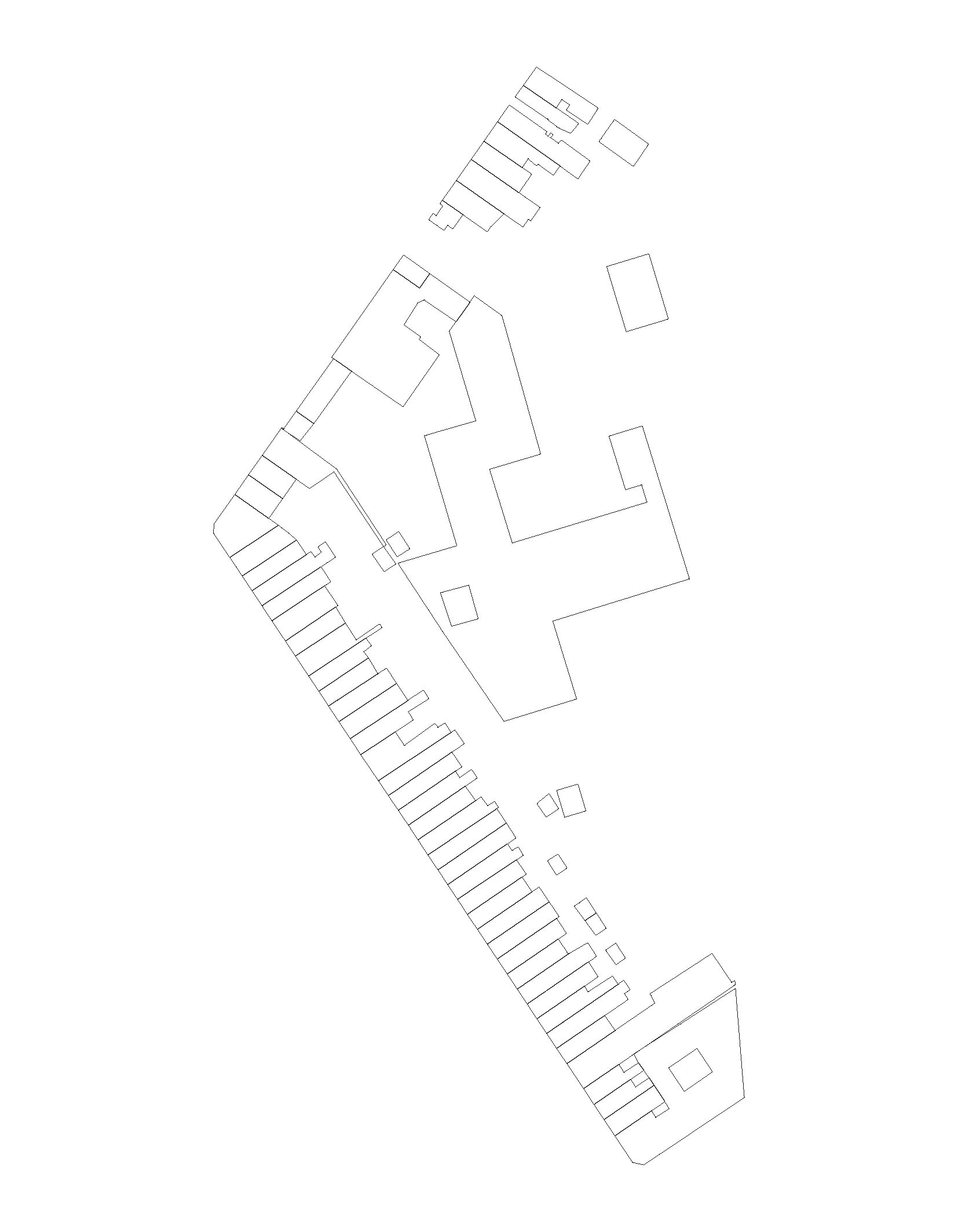

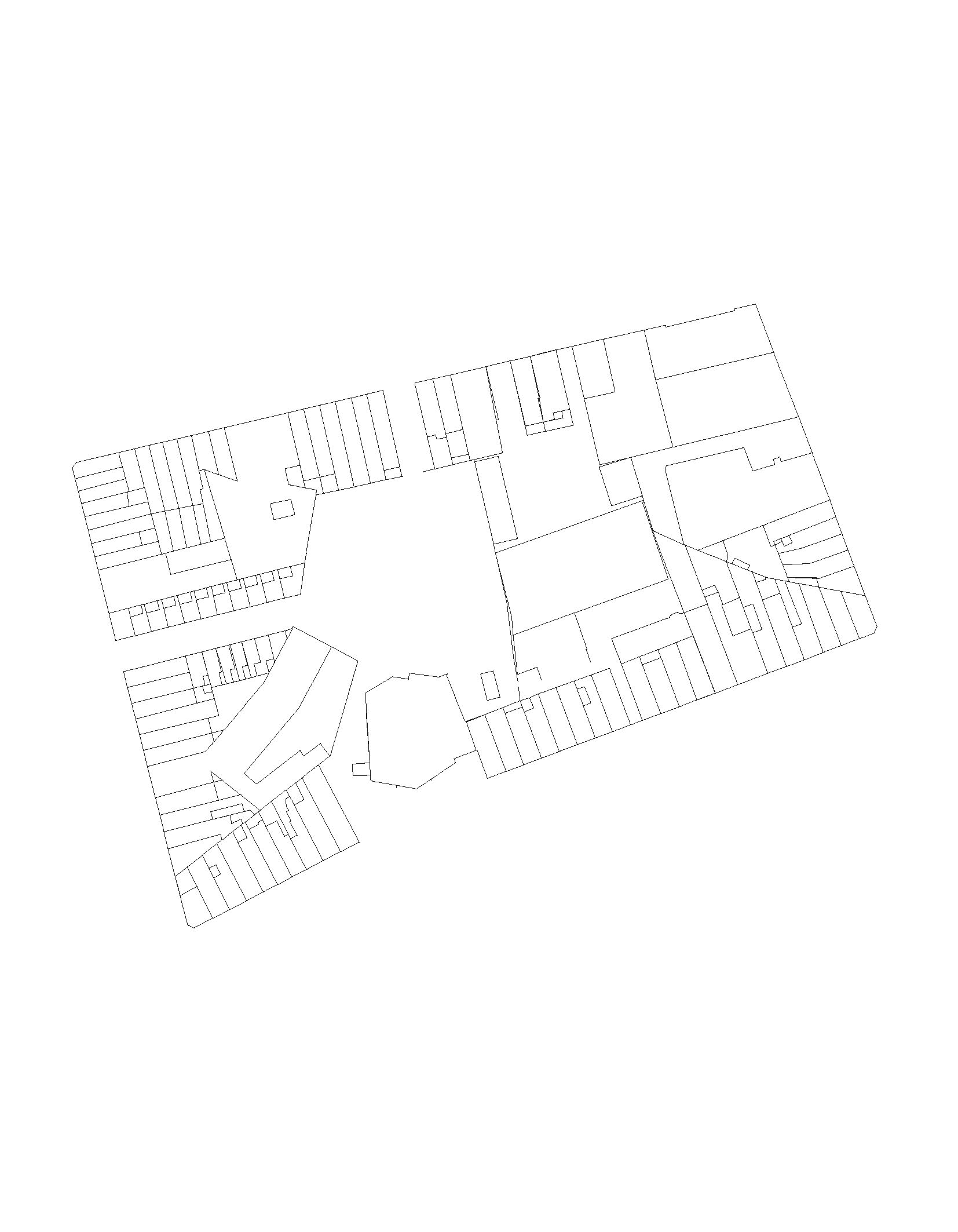

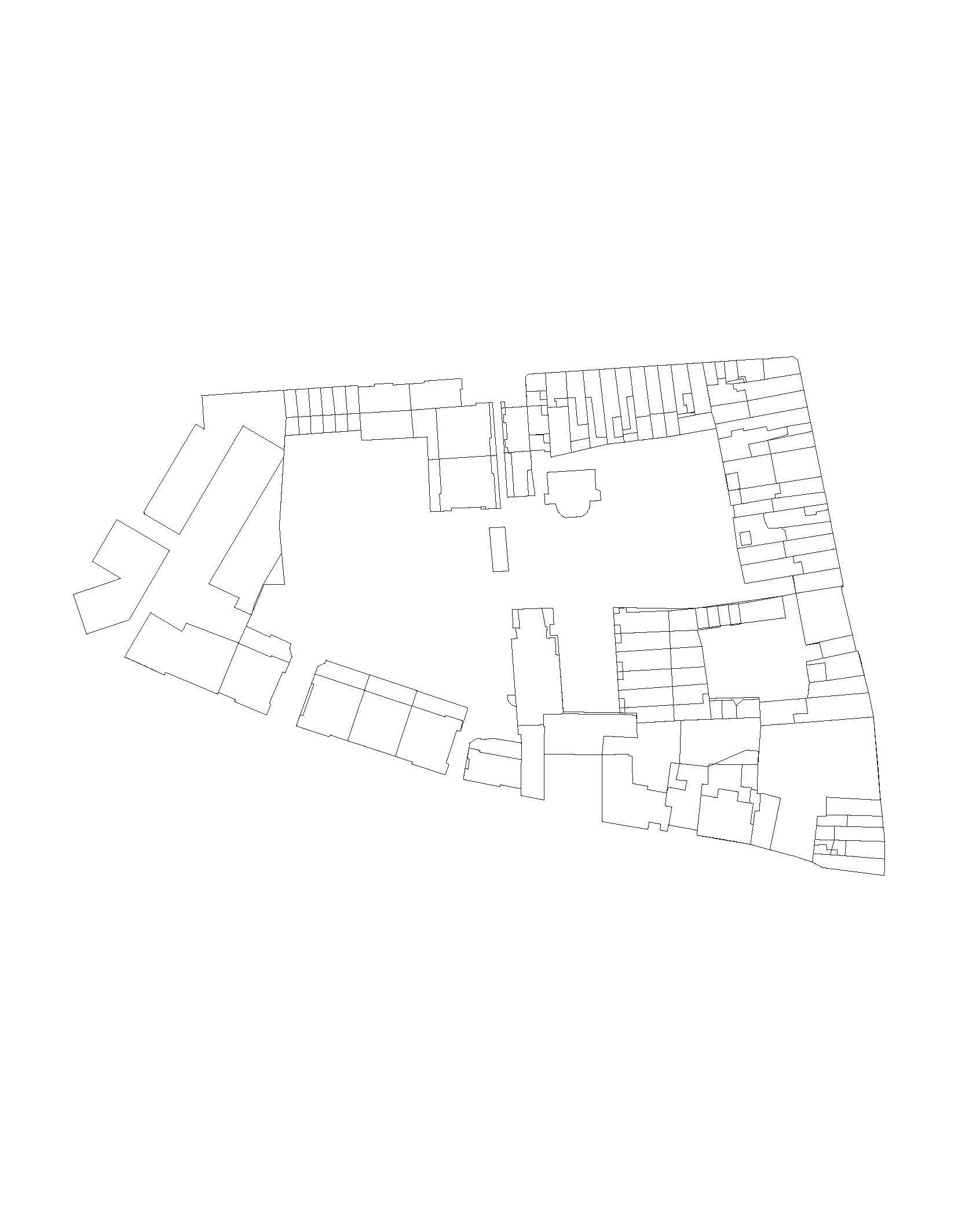

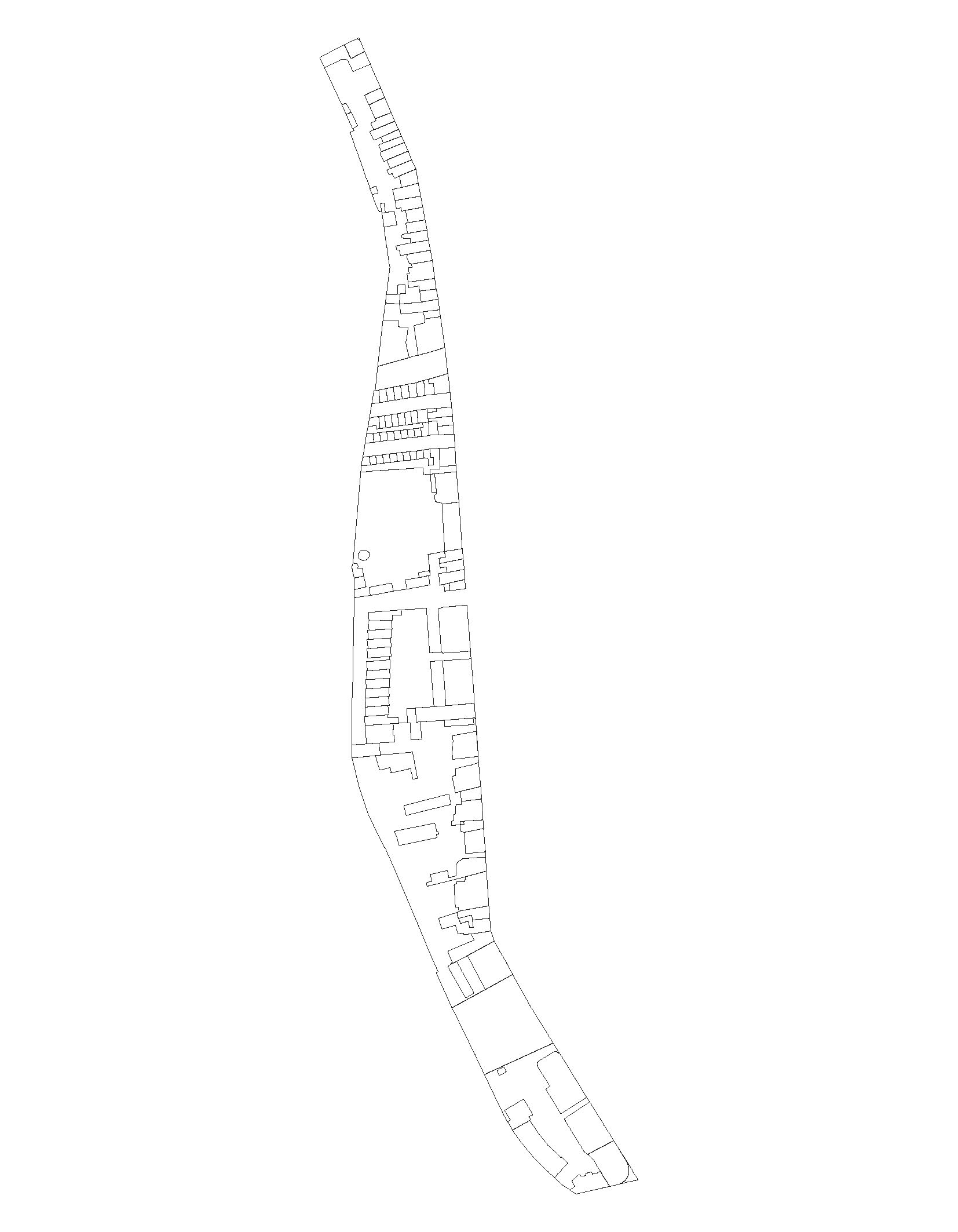

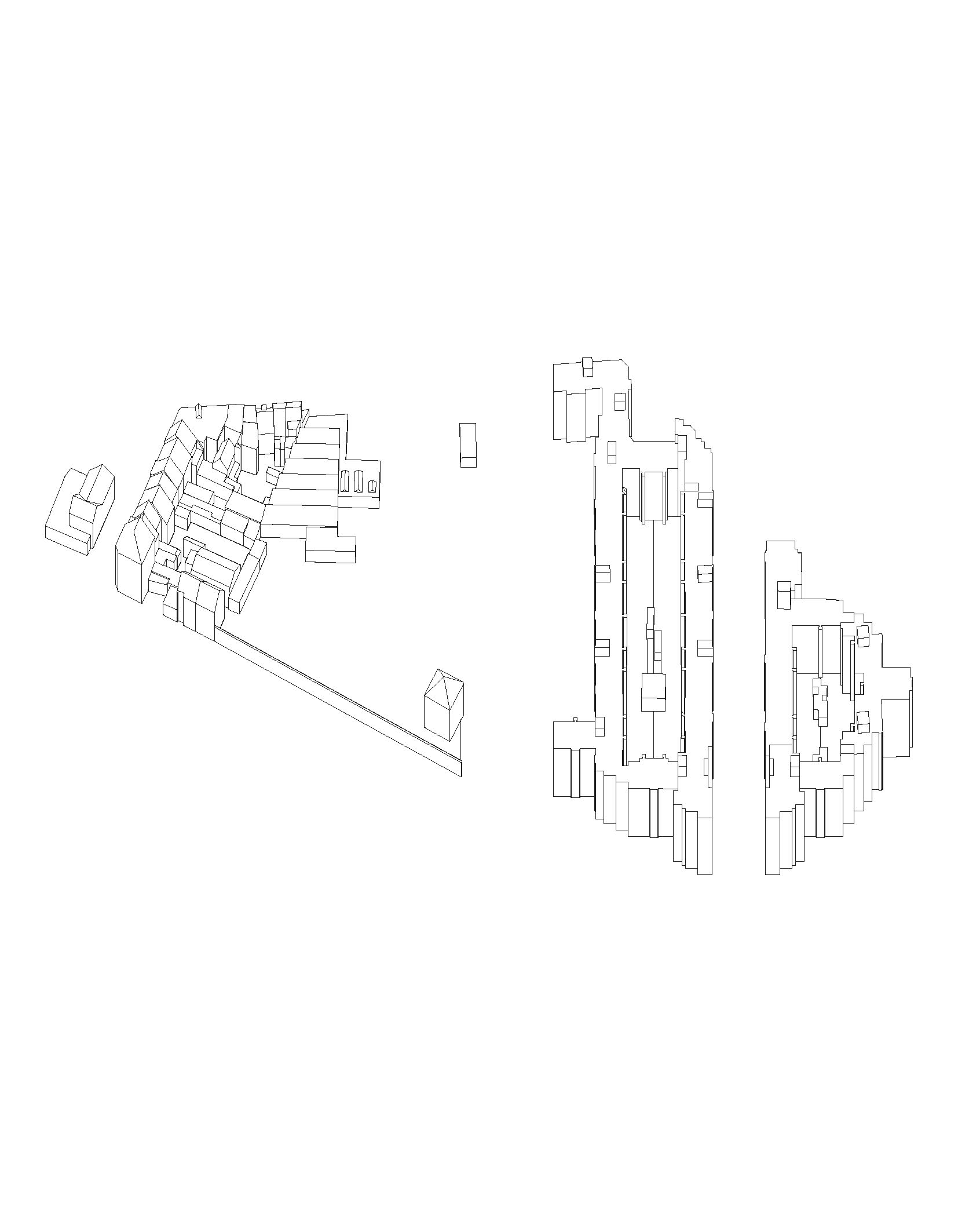

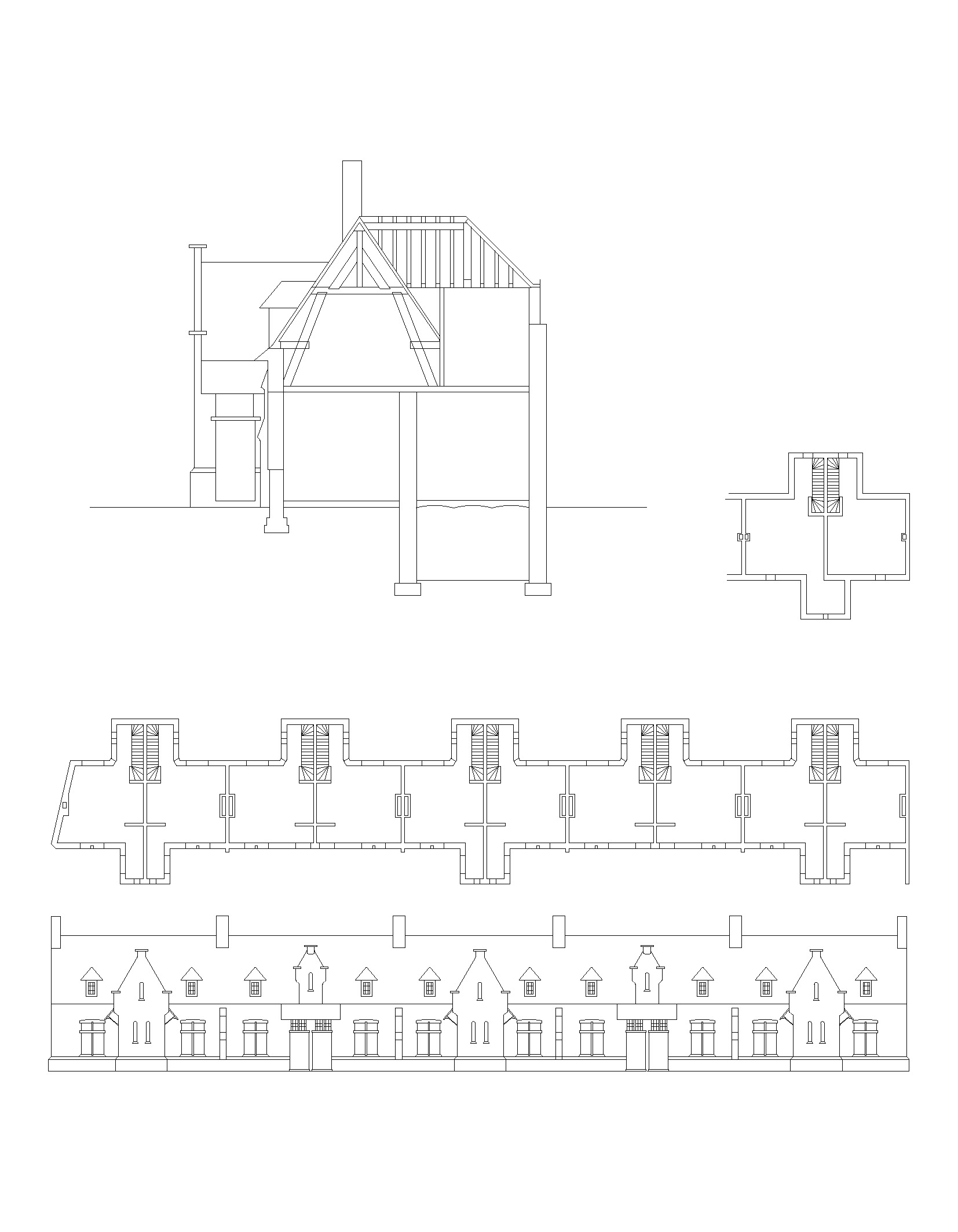

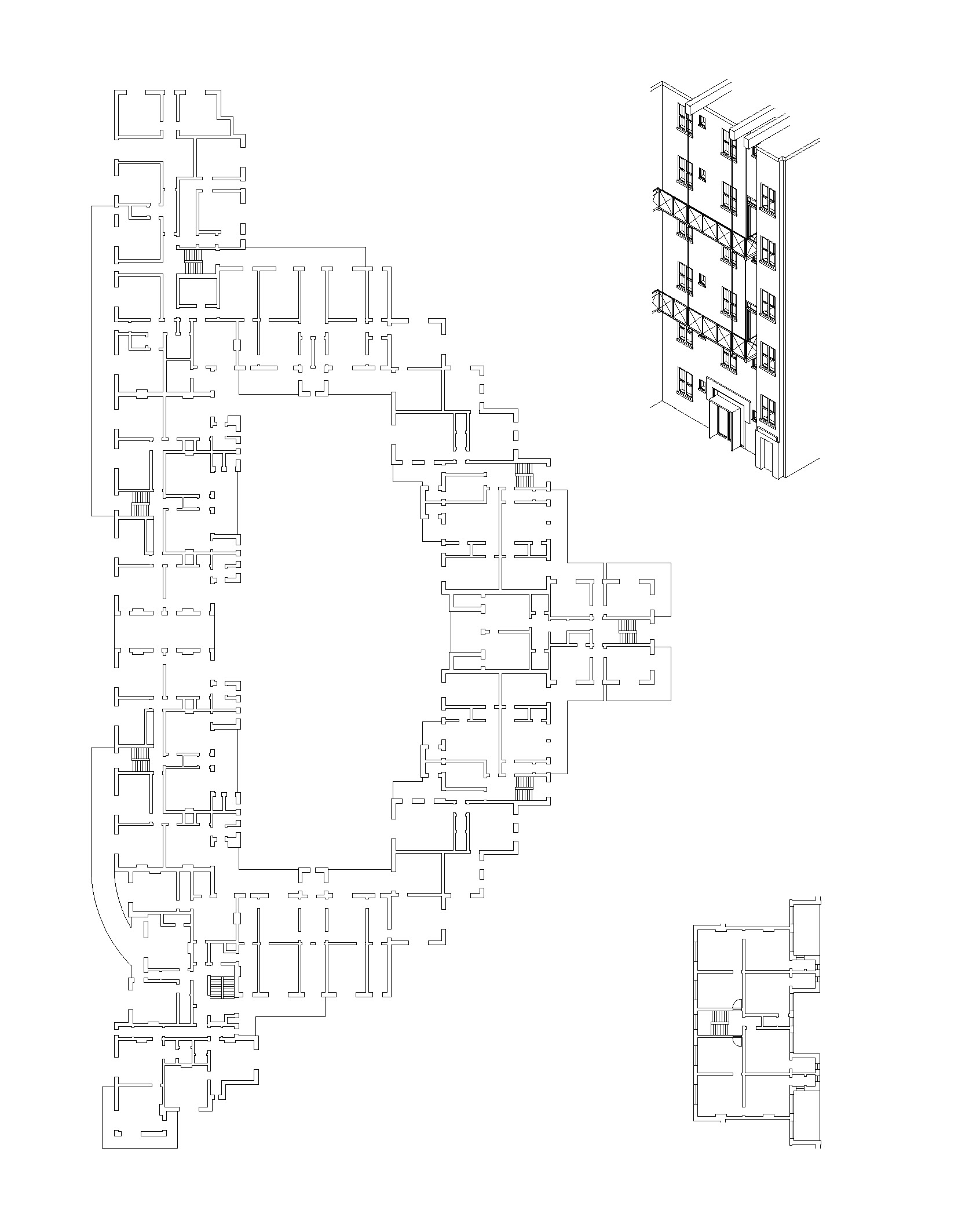

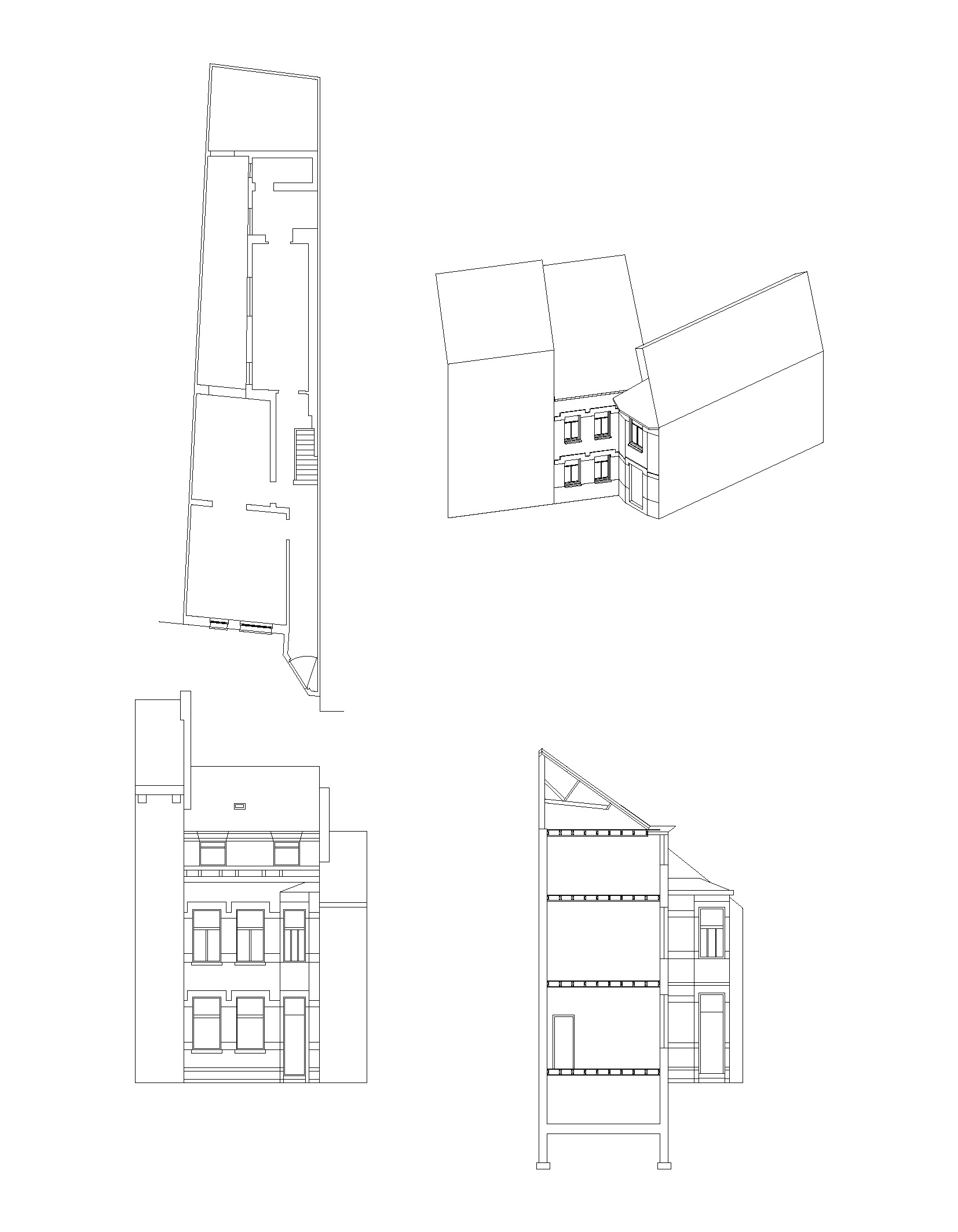

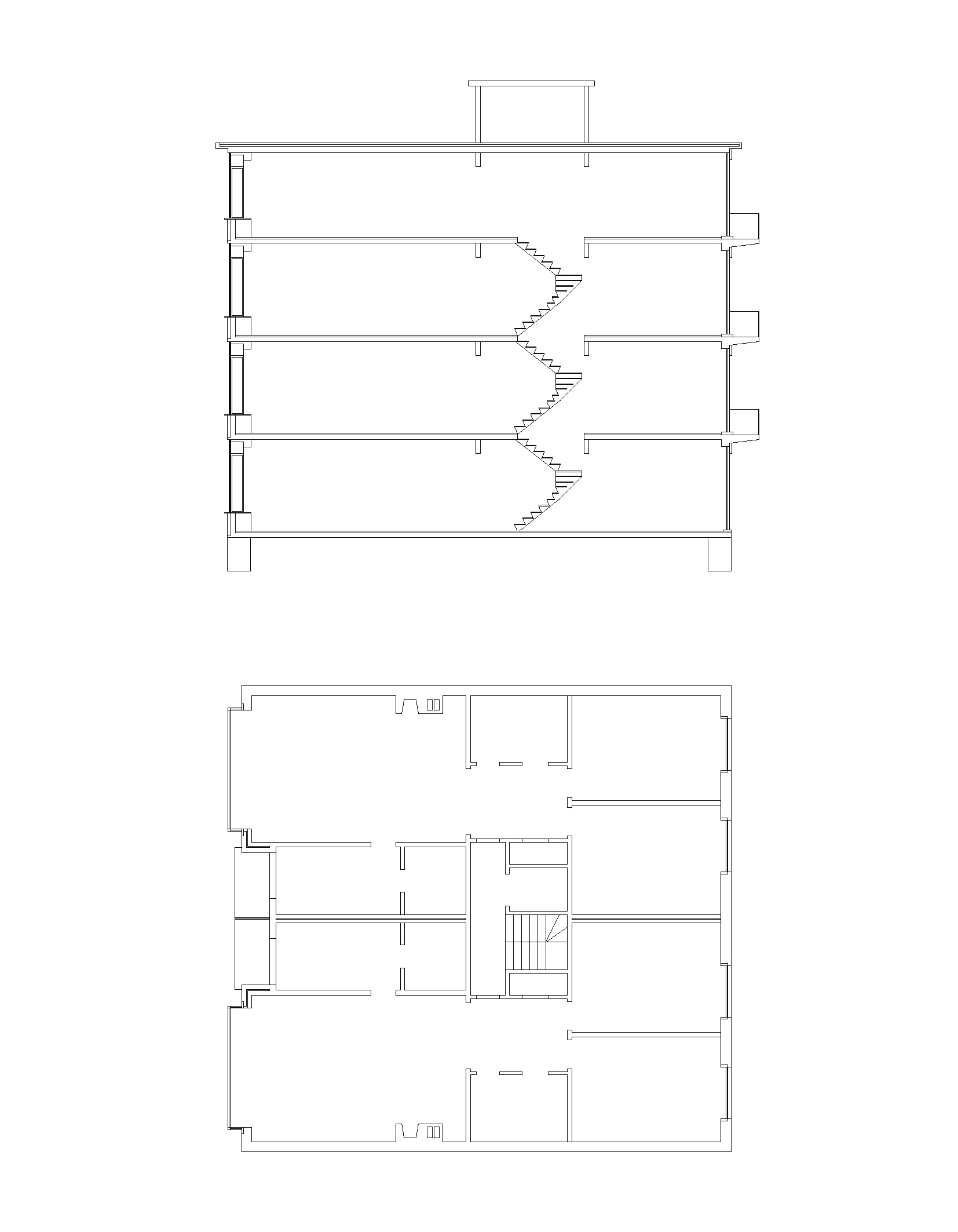

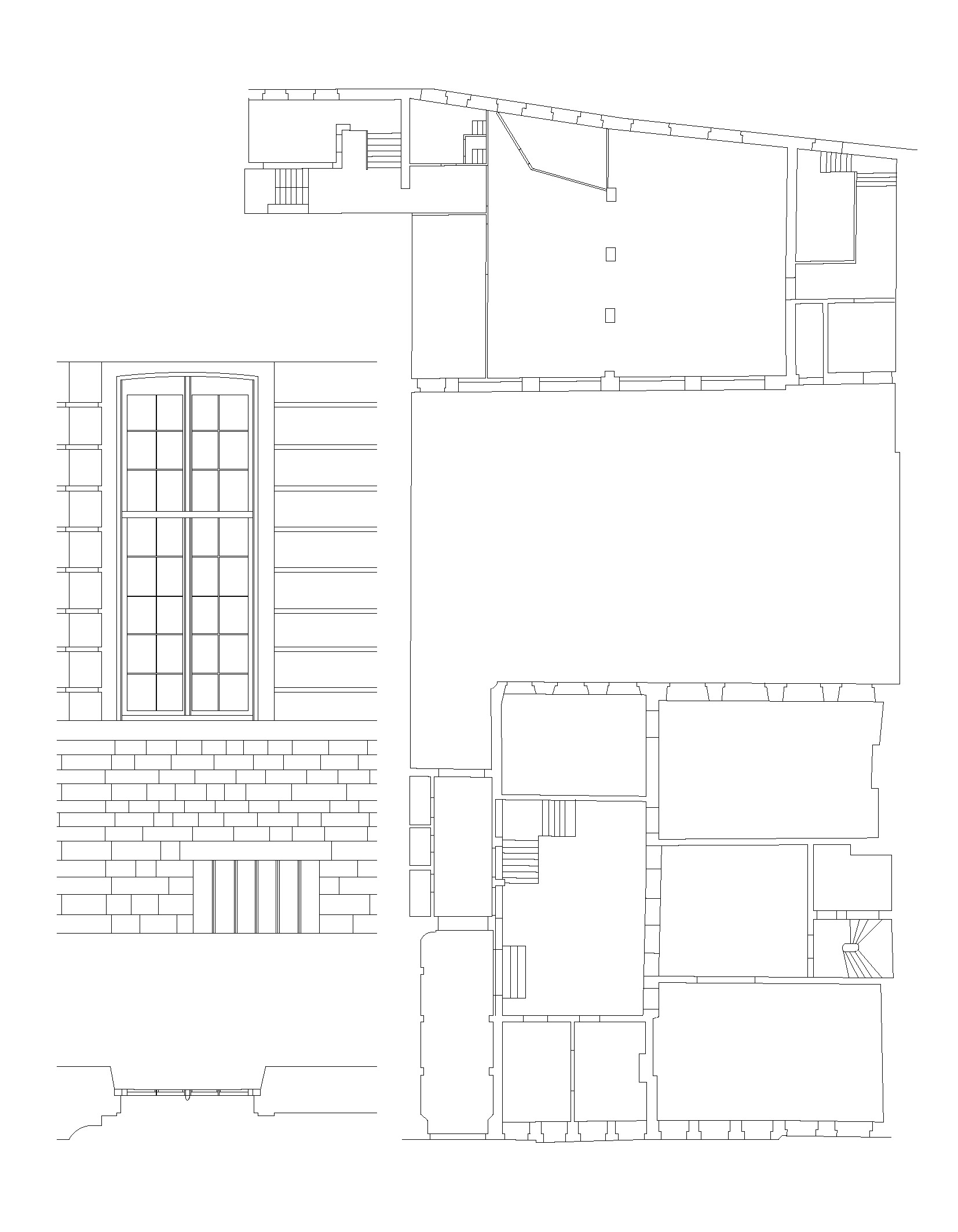

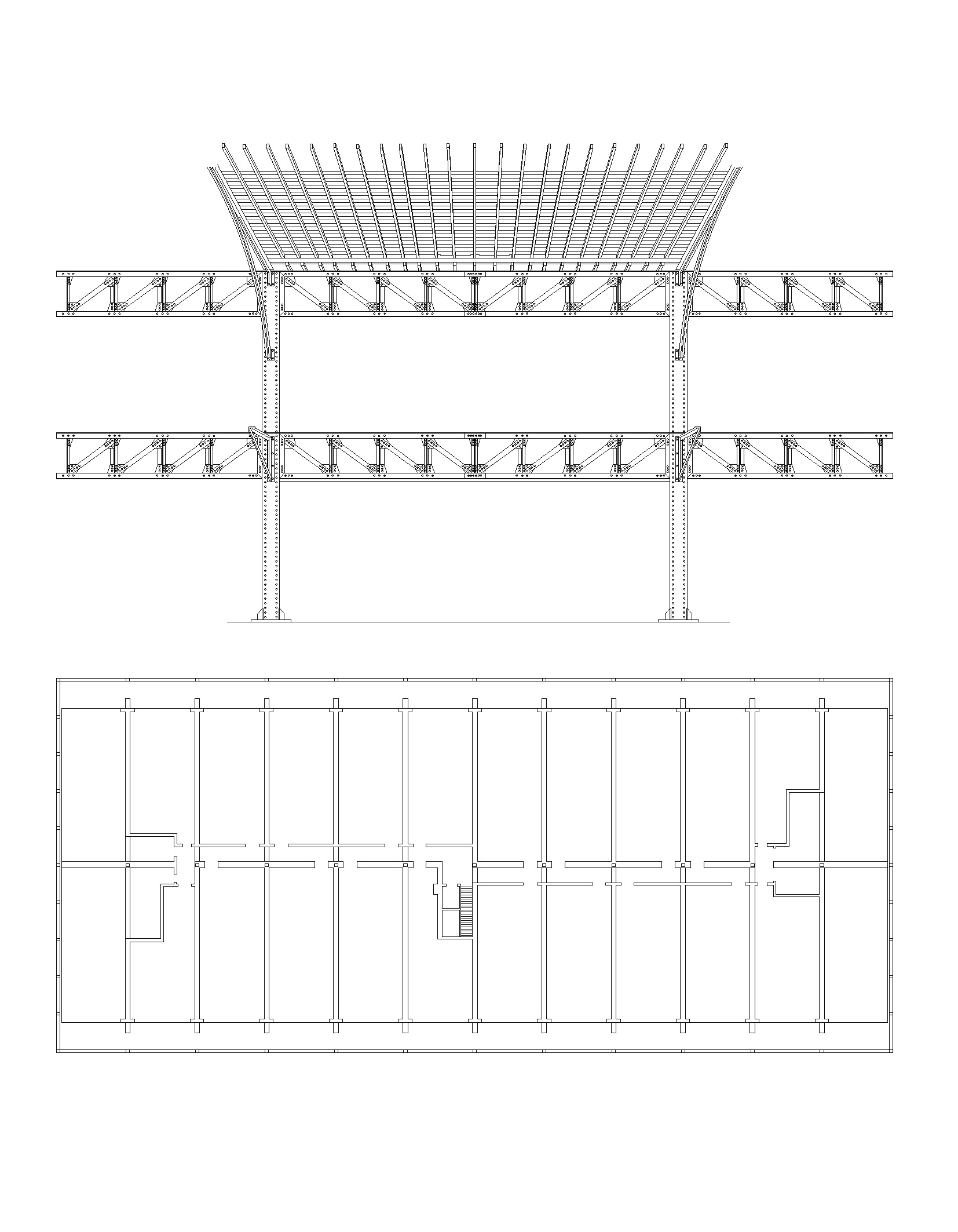

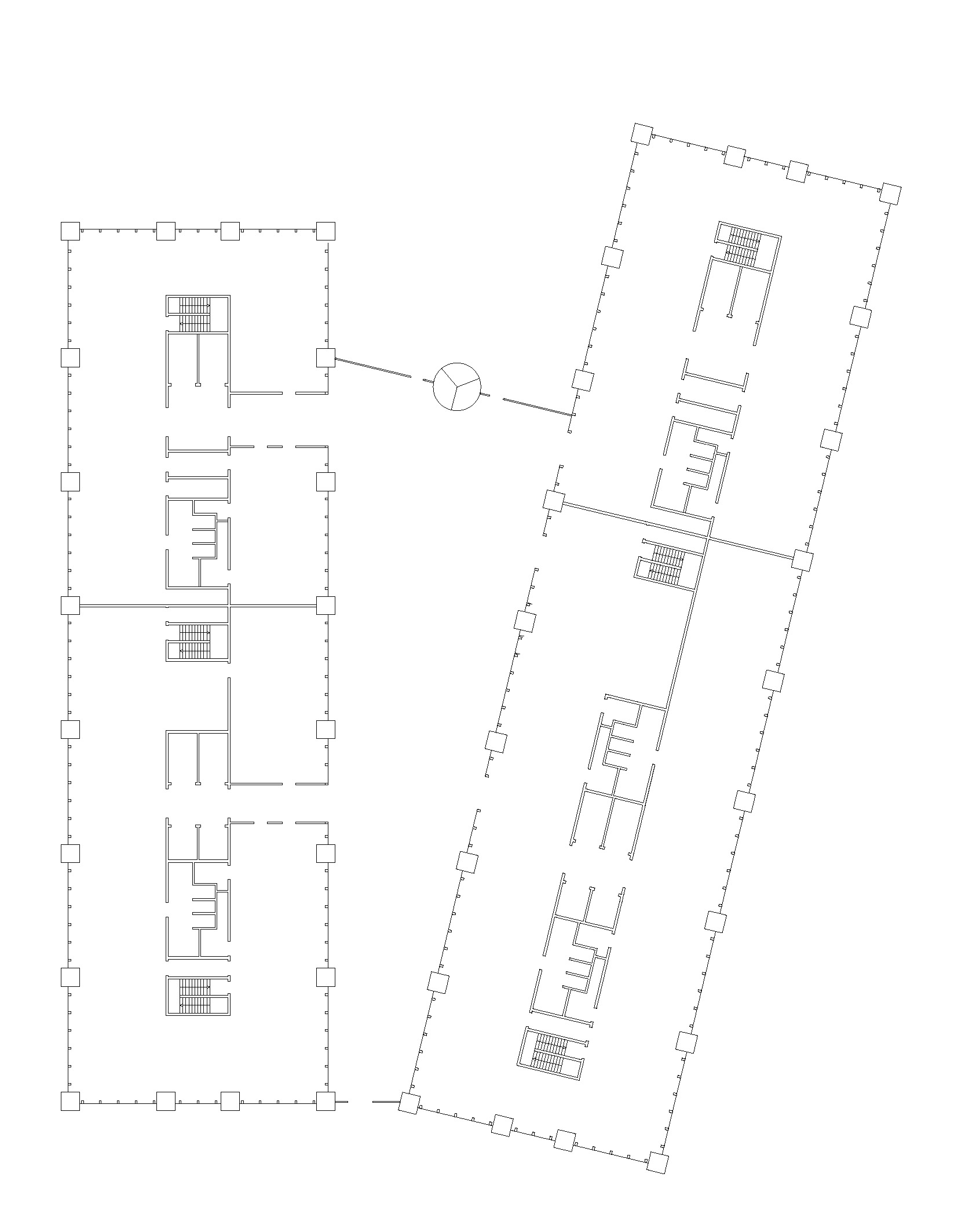

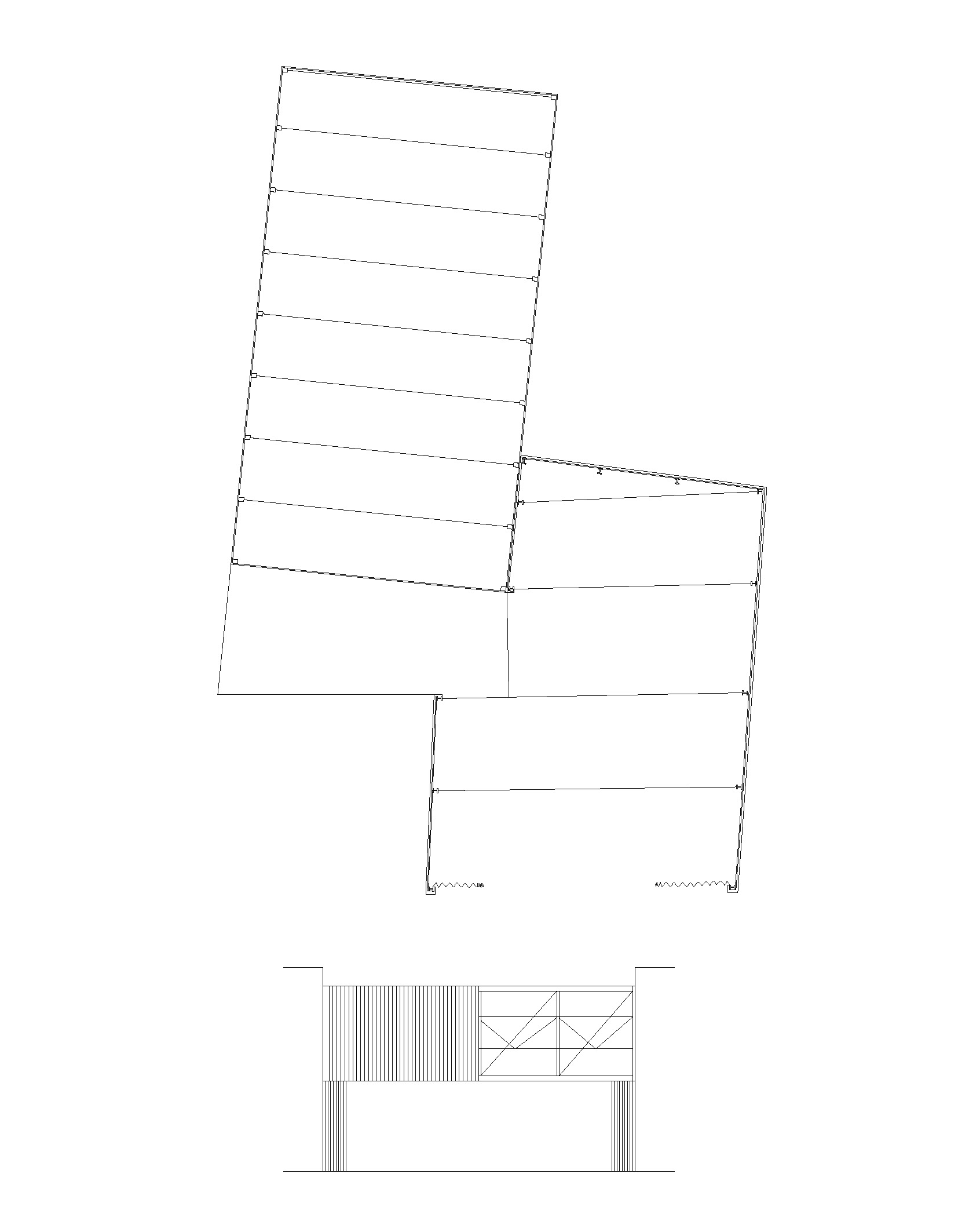

This ‘masterproef’ is part of the ADO Primary structure initiated by GAFPA and led as a master studio in collaboration with Olivier Goethals. During the past years we developed a method of using careful analysis on existing anonymous structures as a starting point for an intervention. The drawing of the existing is used to fuel an ongoing catalogue of research material (primary structure.net) which can be used as a source material. In it we are interested in the basic primary skeleton of architecture and the pragmatic beauty of building solutions which one can find where a building system is compromised for economic, contextual or programmatic reasons. The final result is a primary structure which has a generic quality in terms of programmatic flexibility but a highly specific contextual character. It is an intelligent ruin which in the vision of bOb Van Reeth should last at least 400 years.

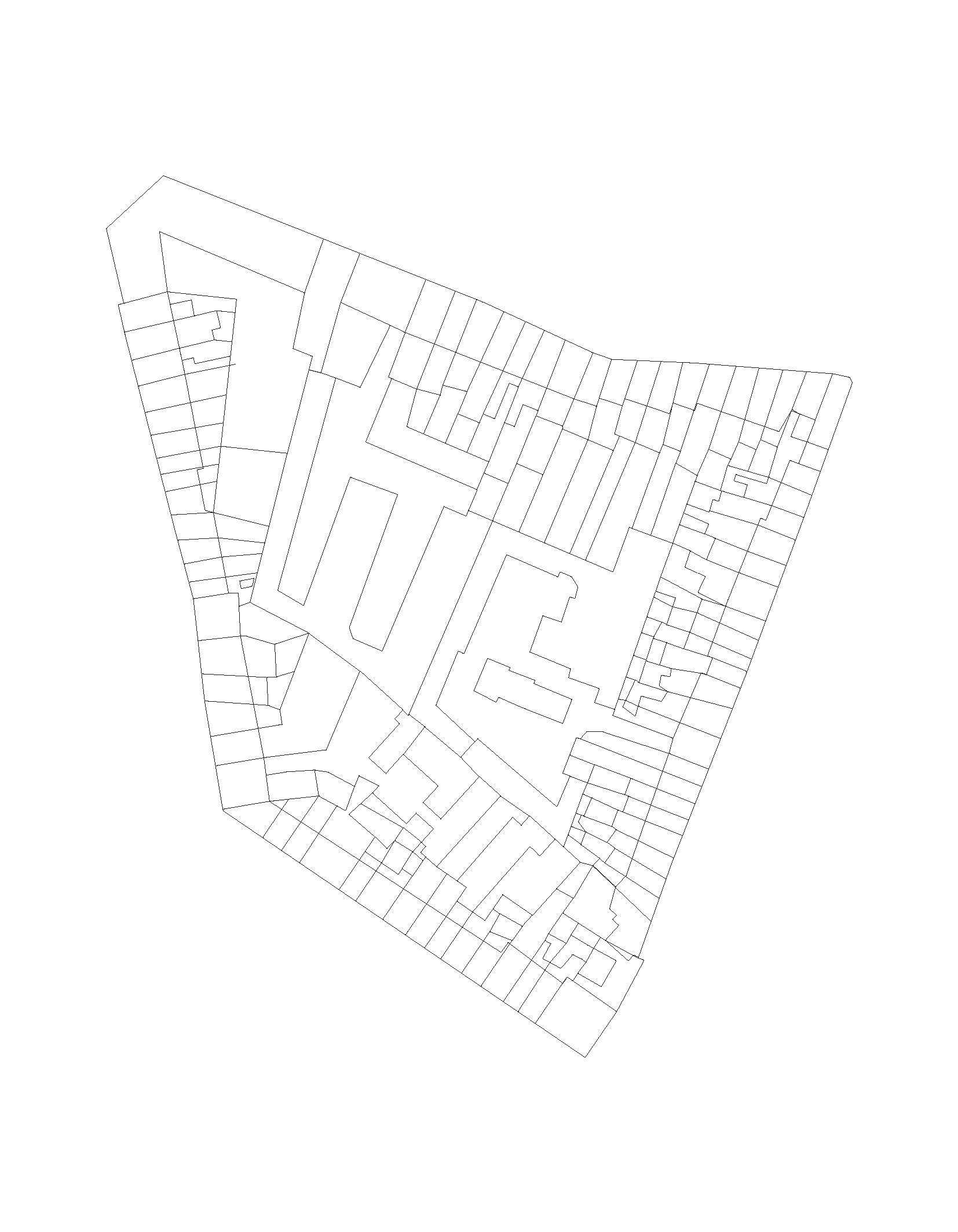

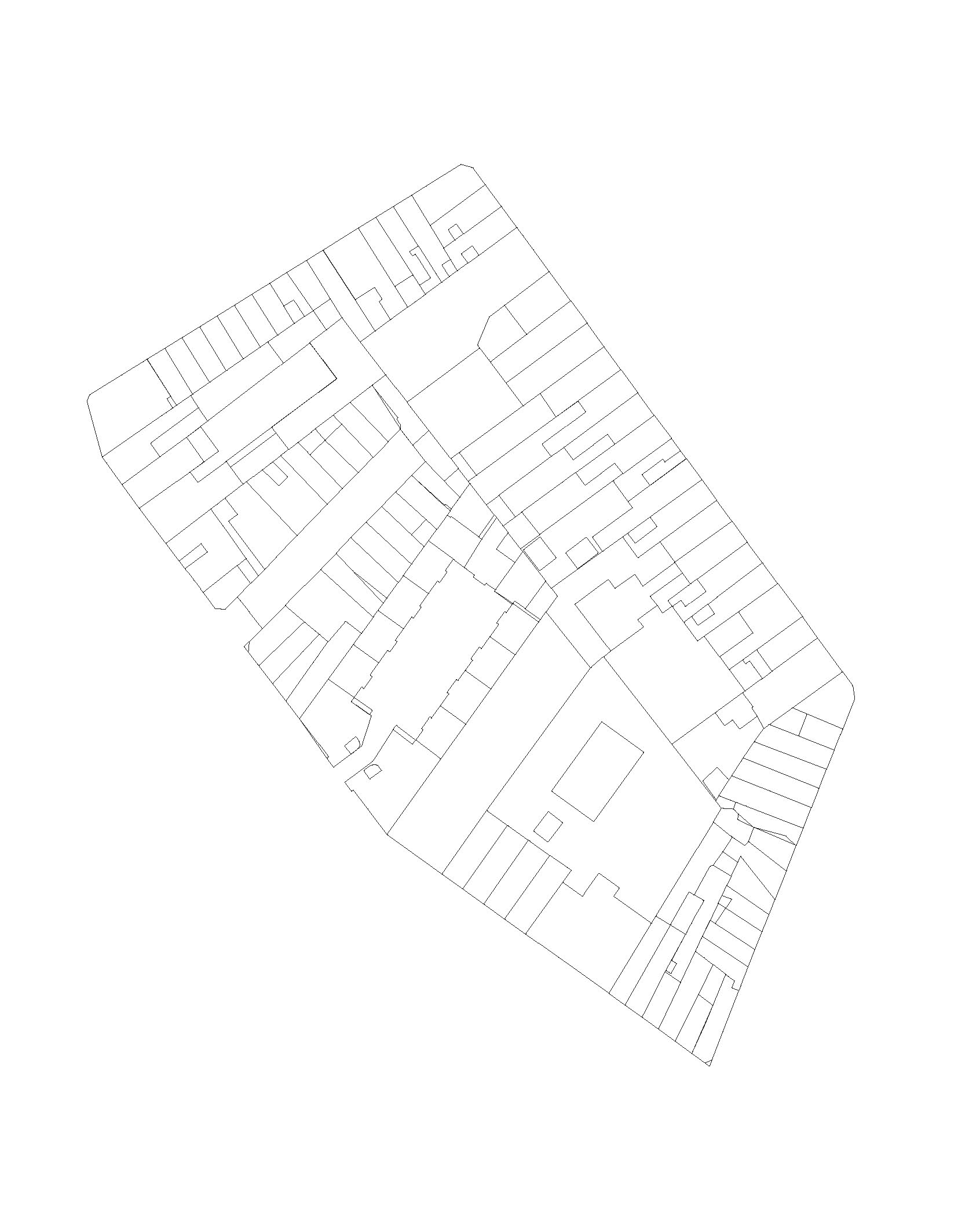

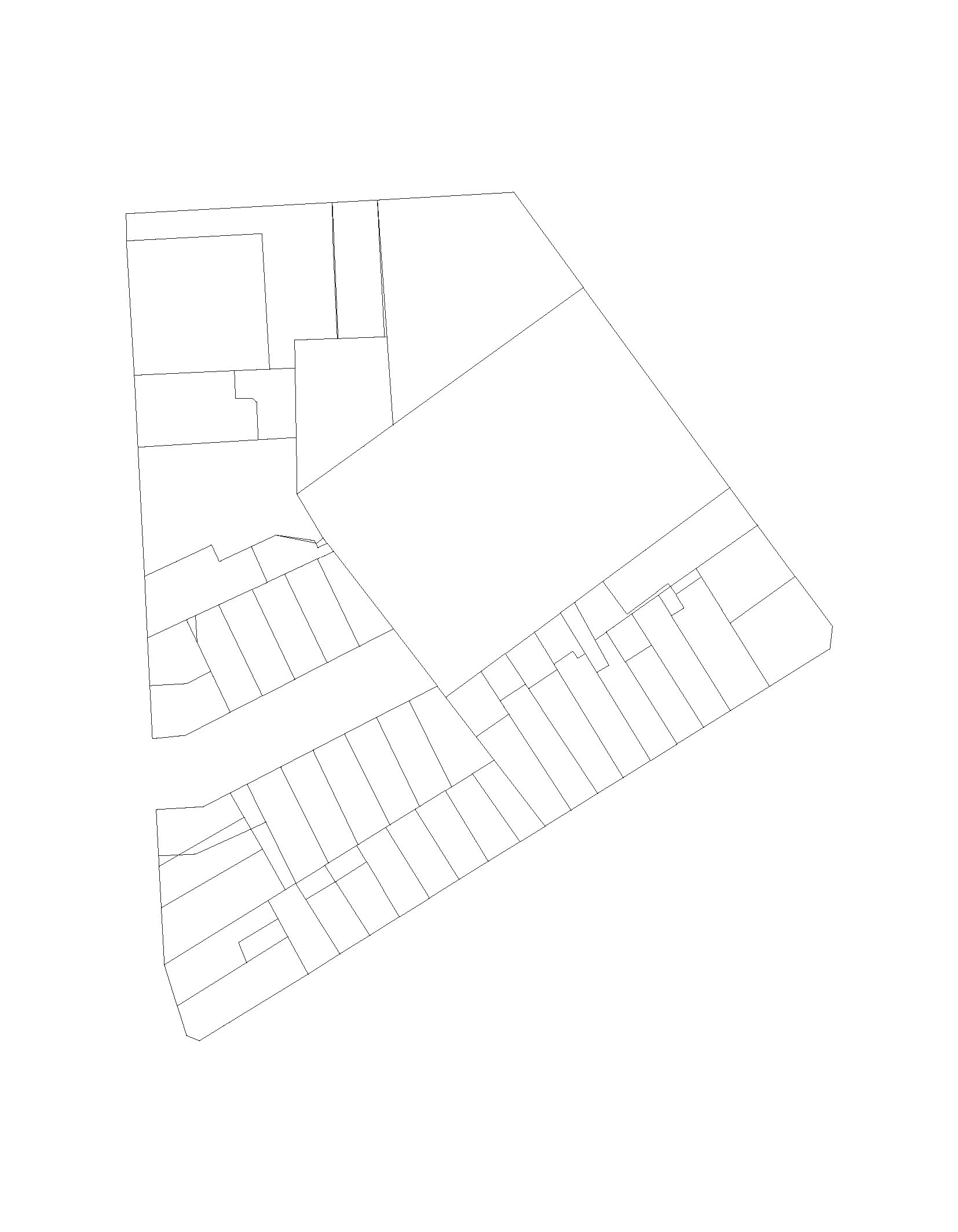

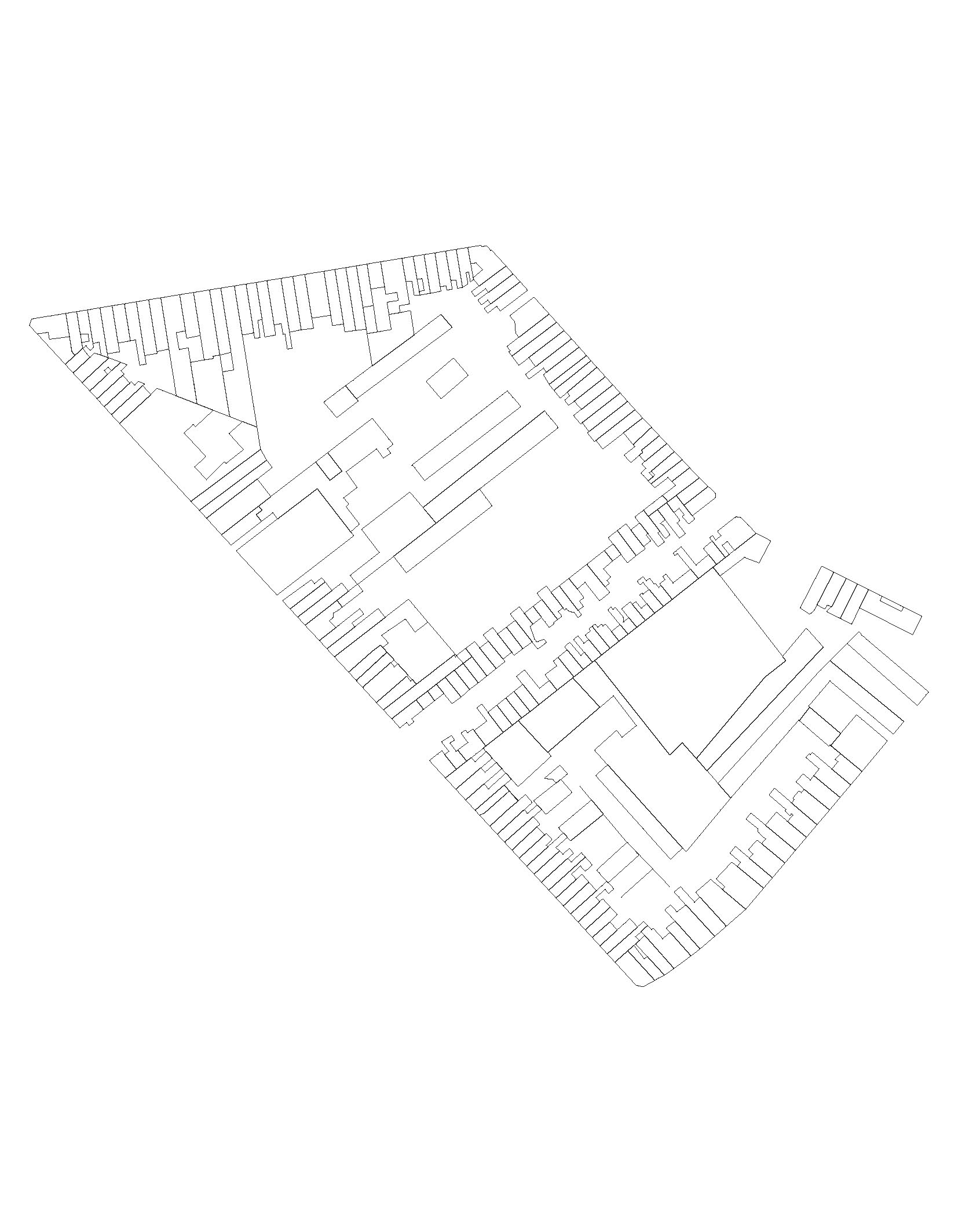

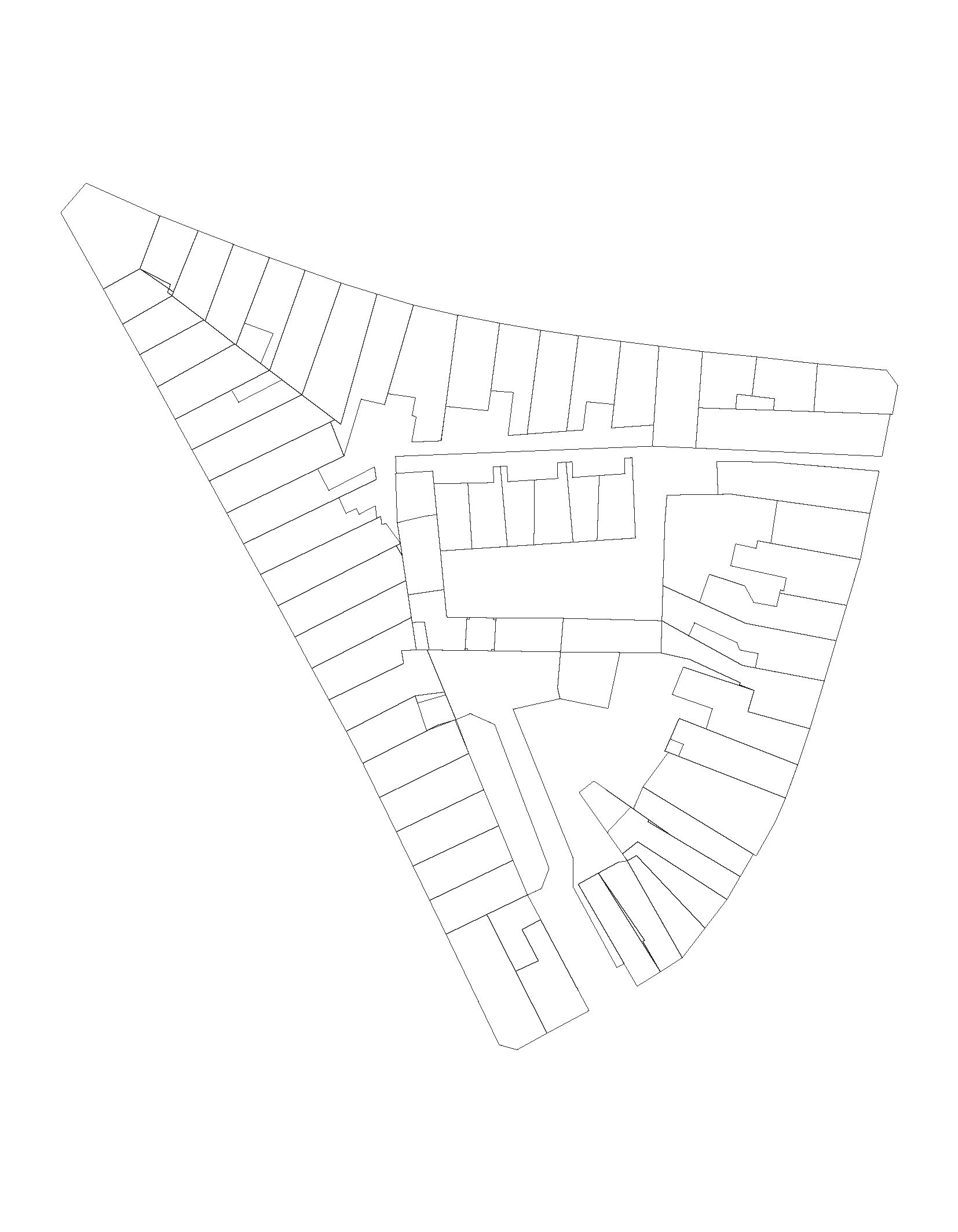

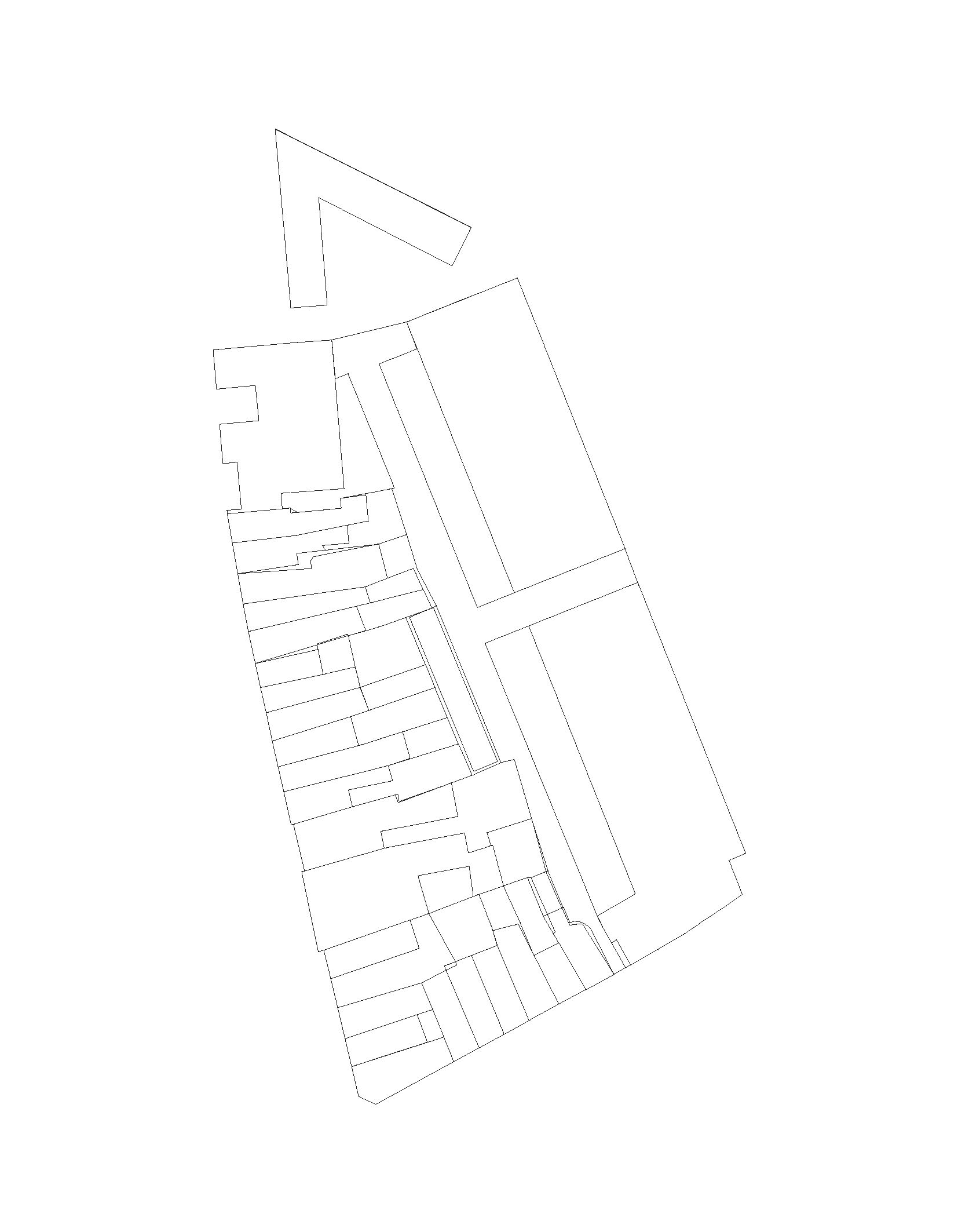

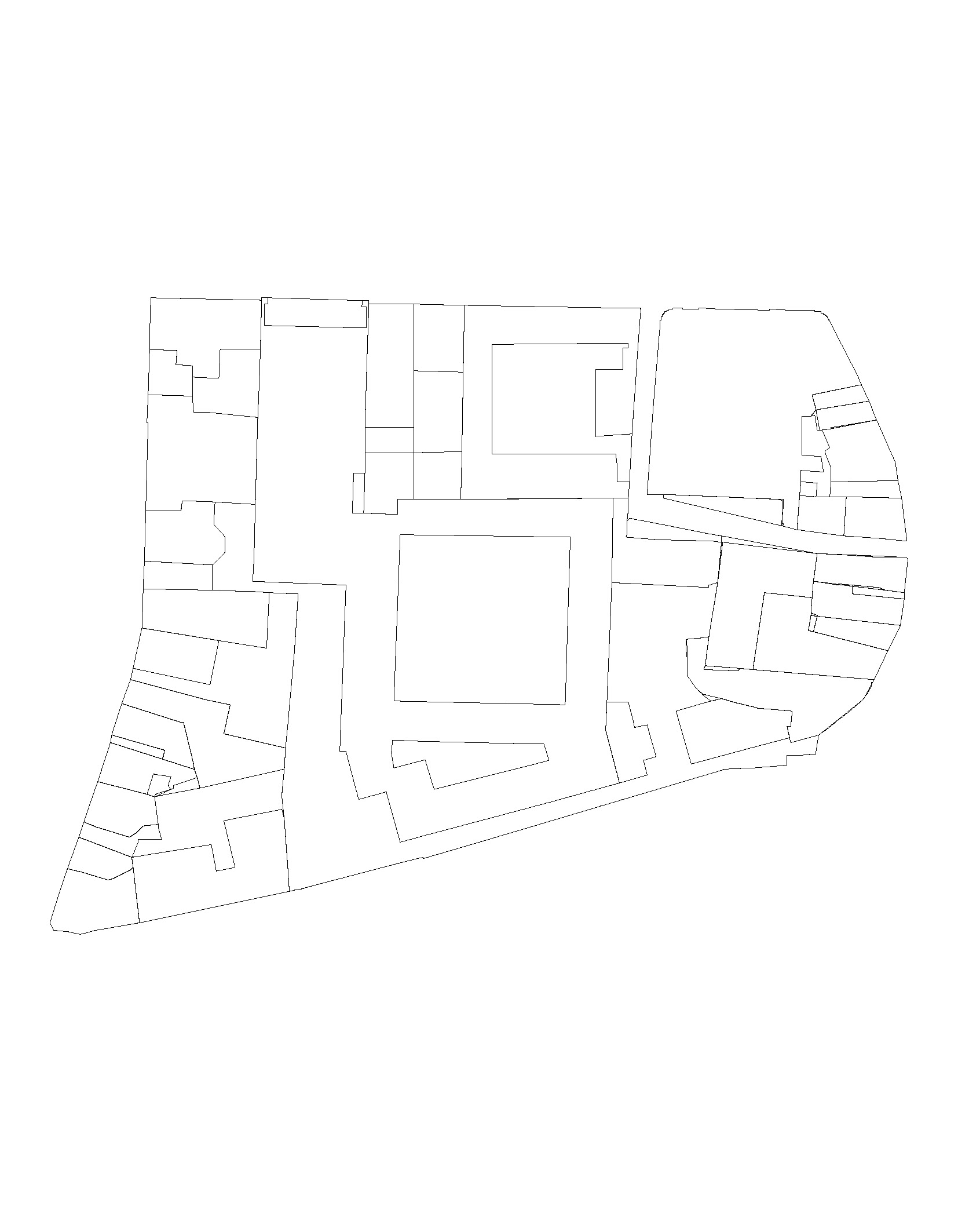

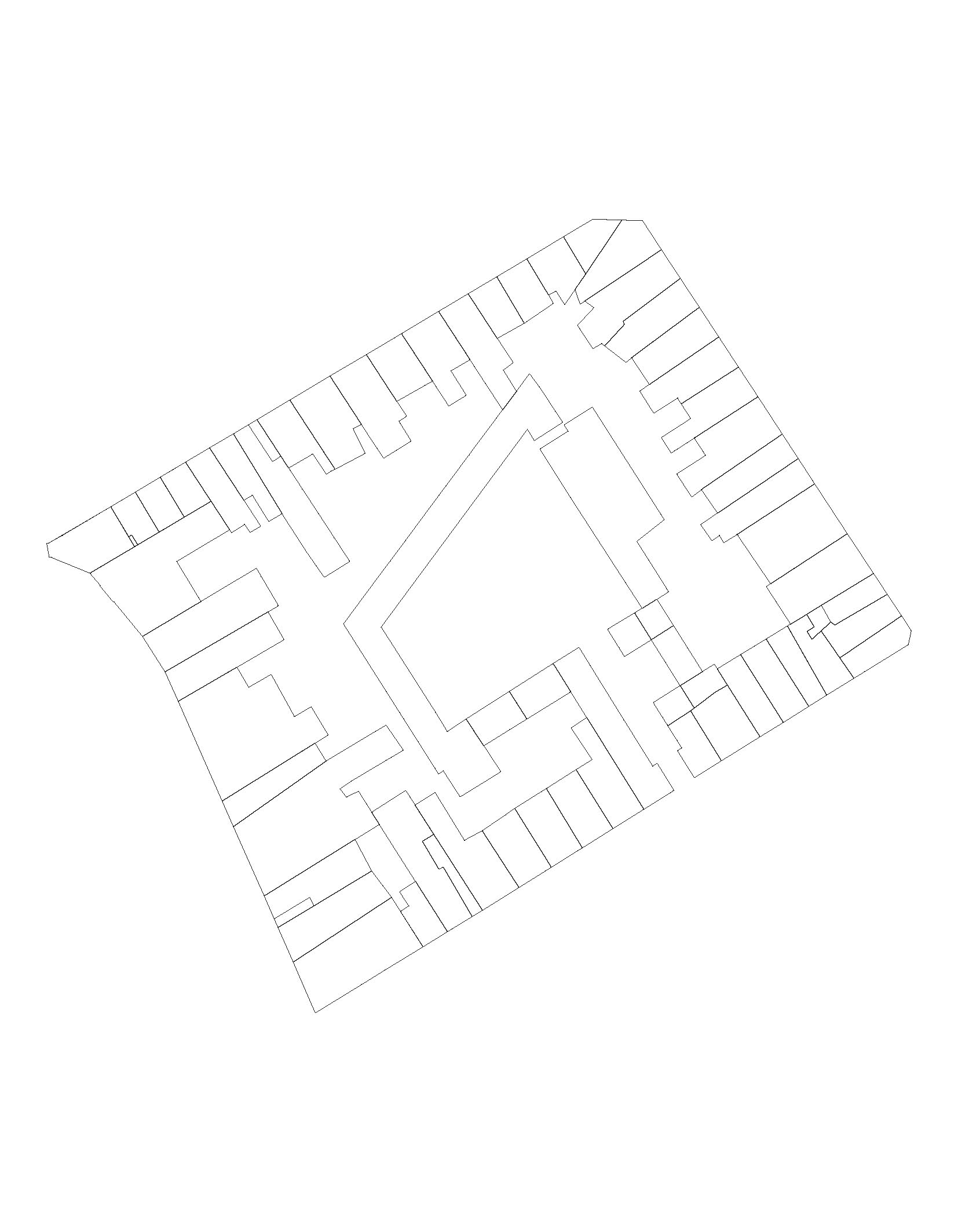

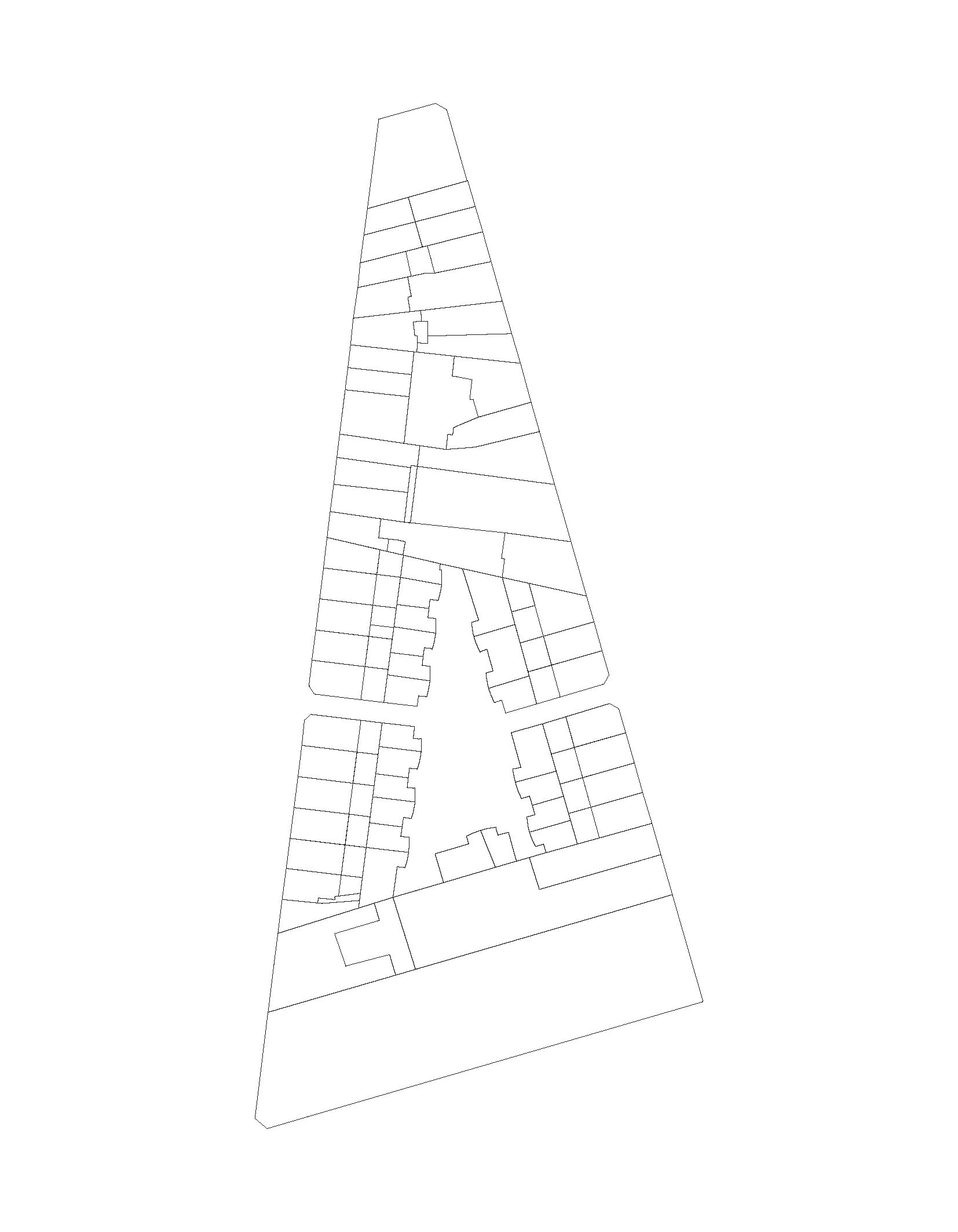

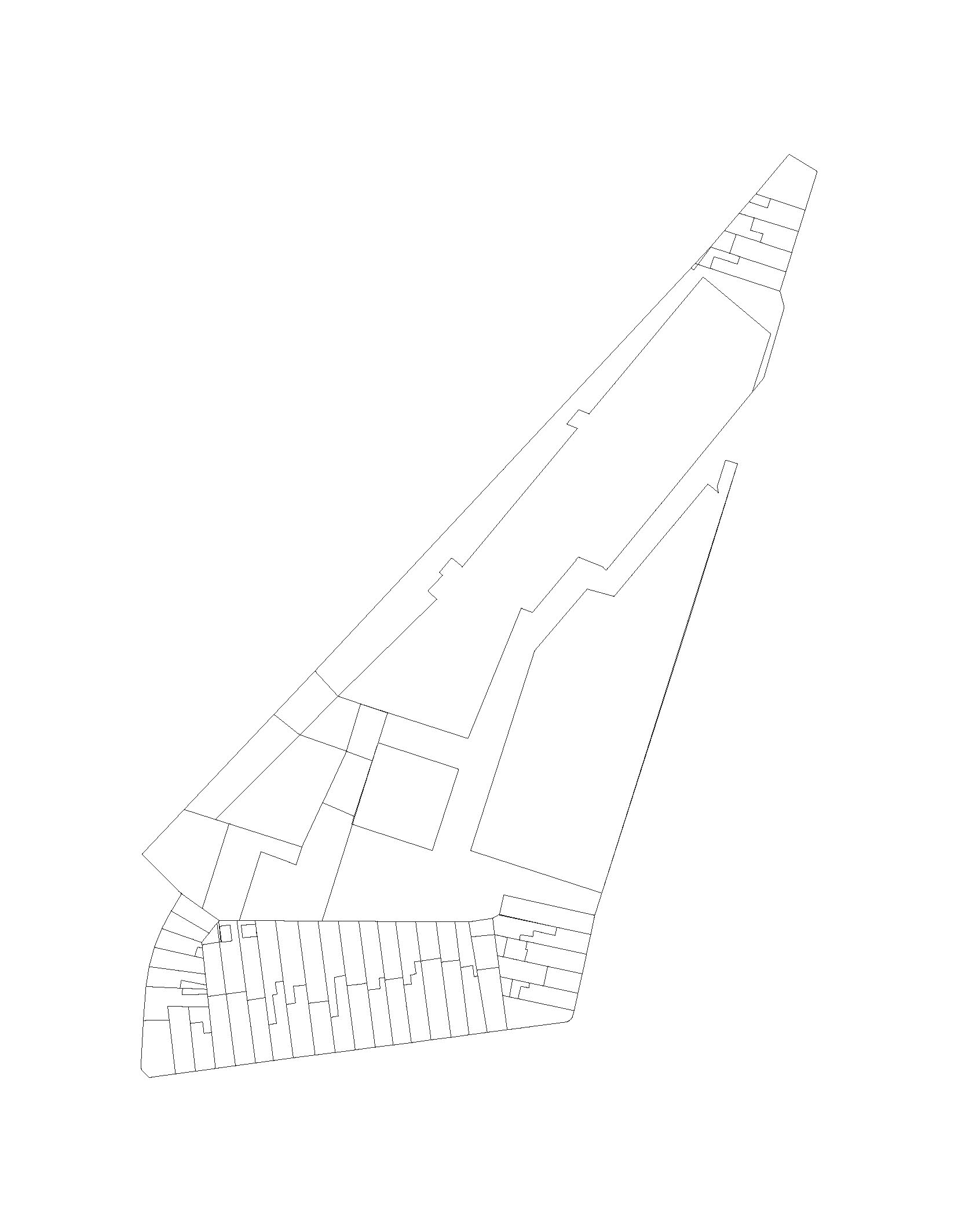

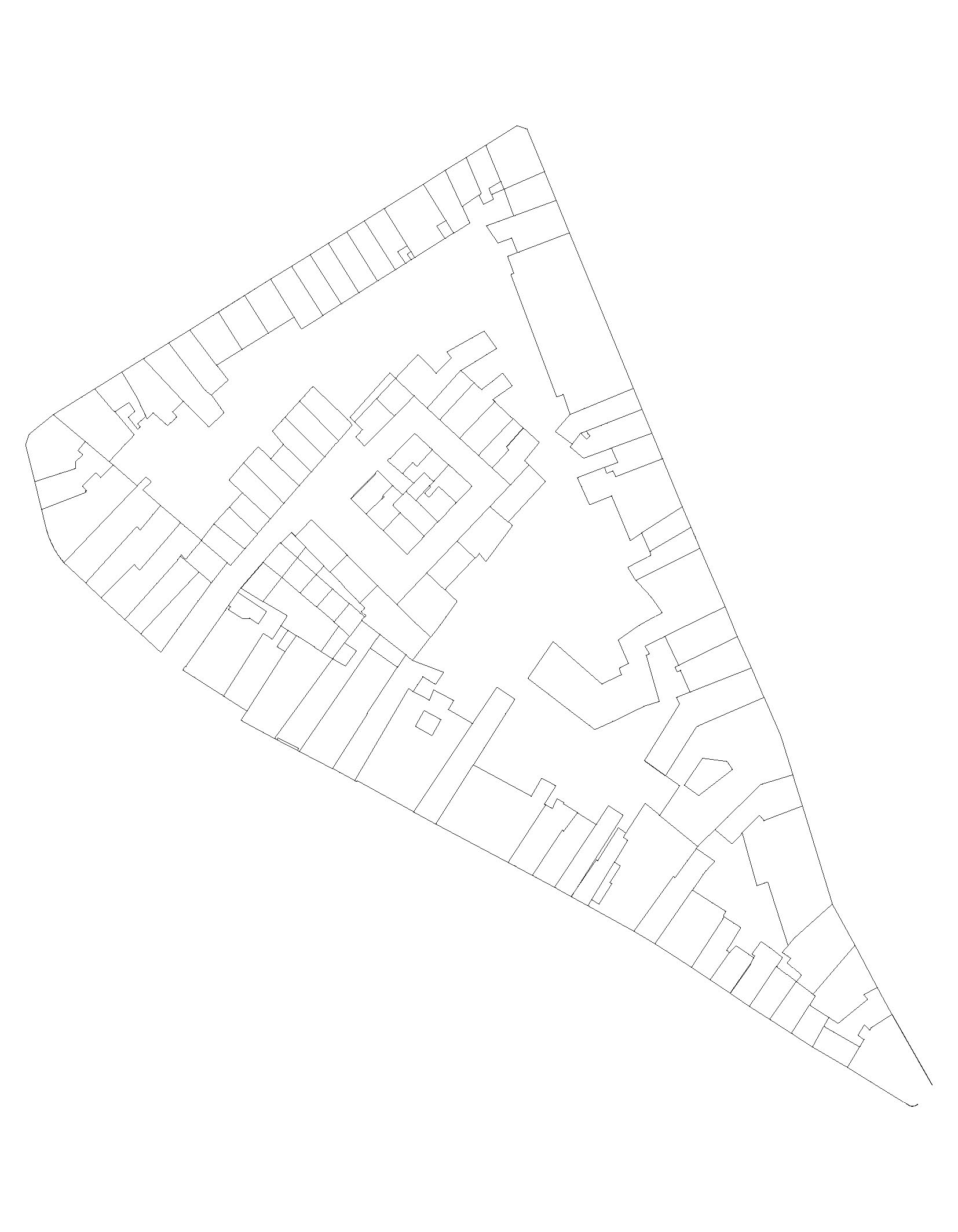

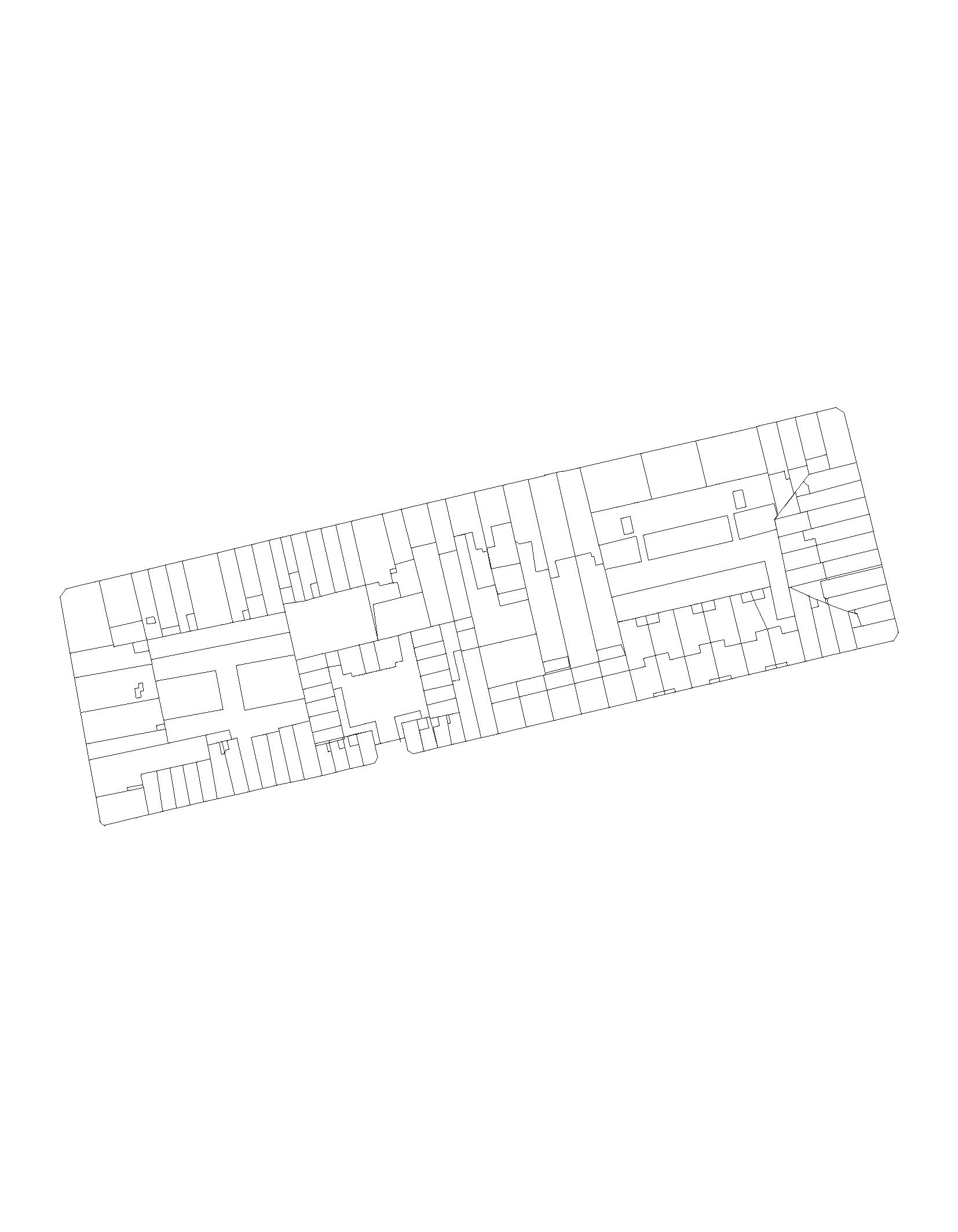

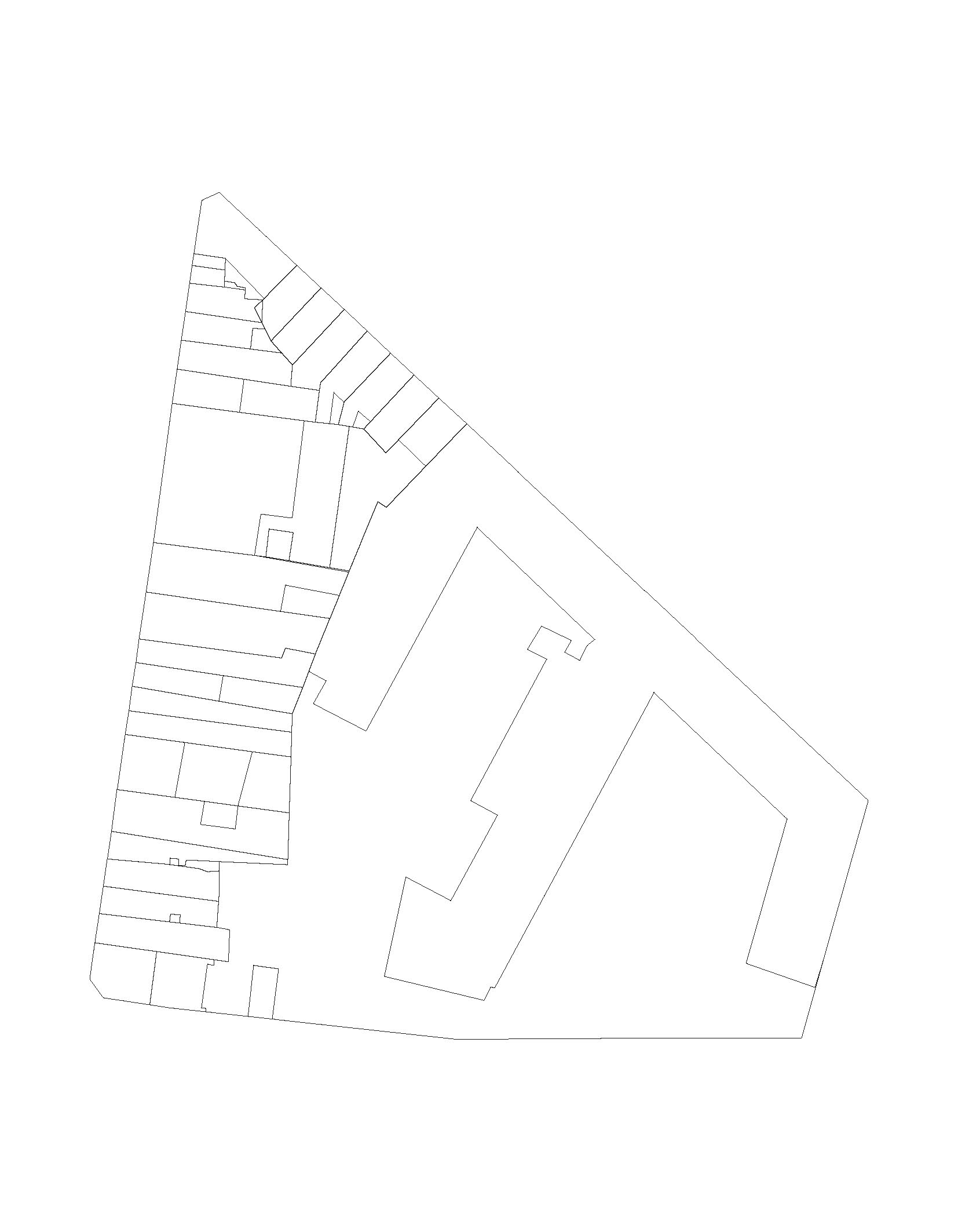

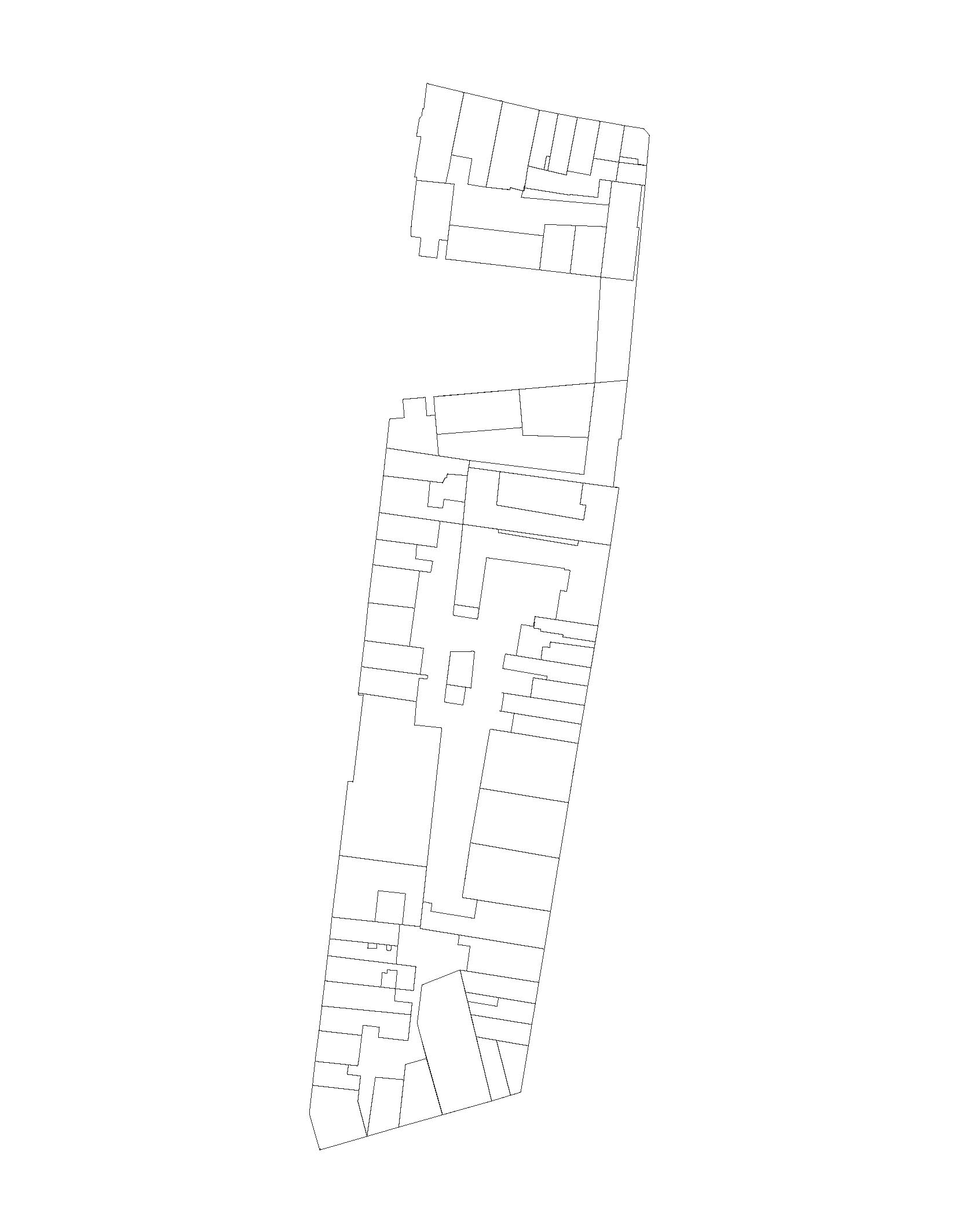

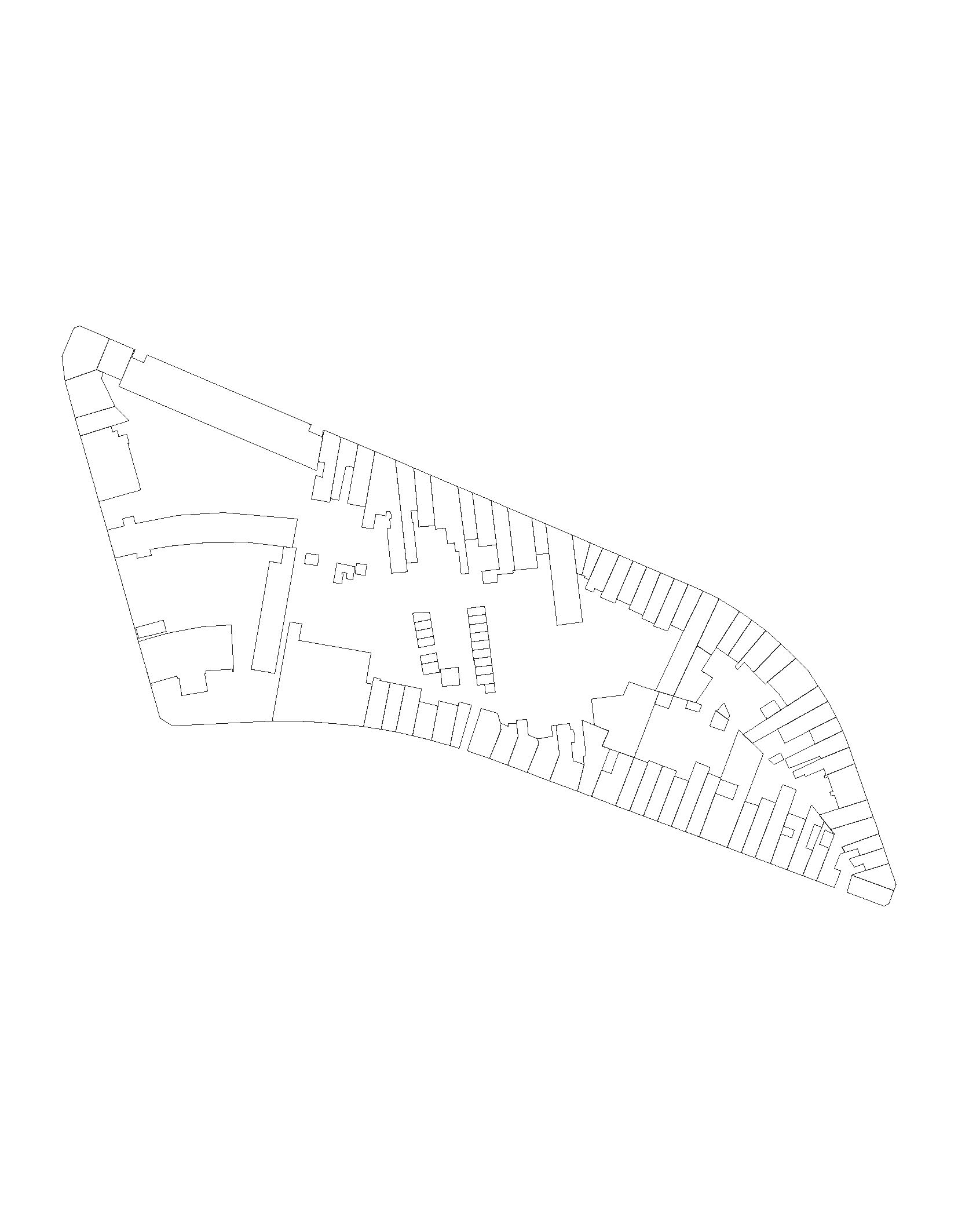

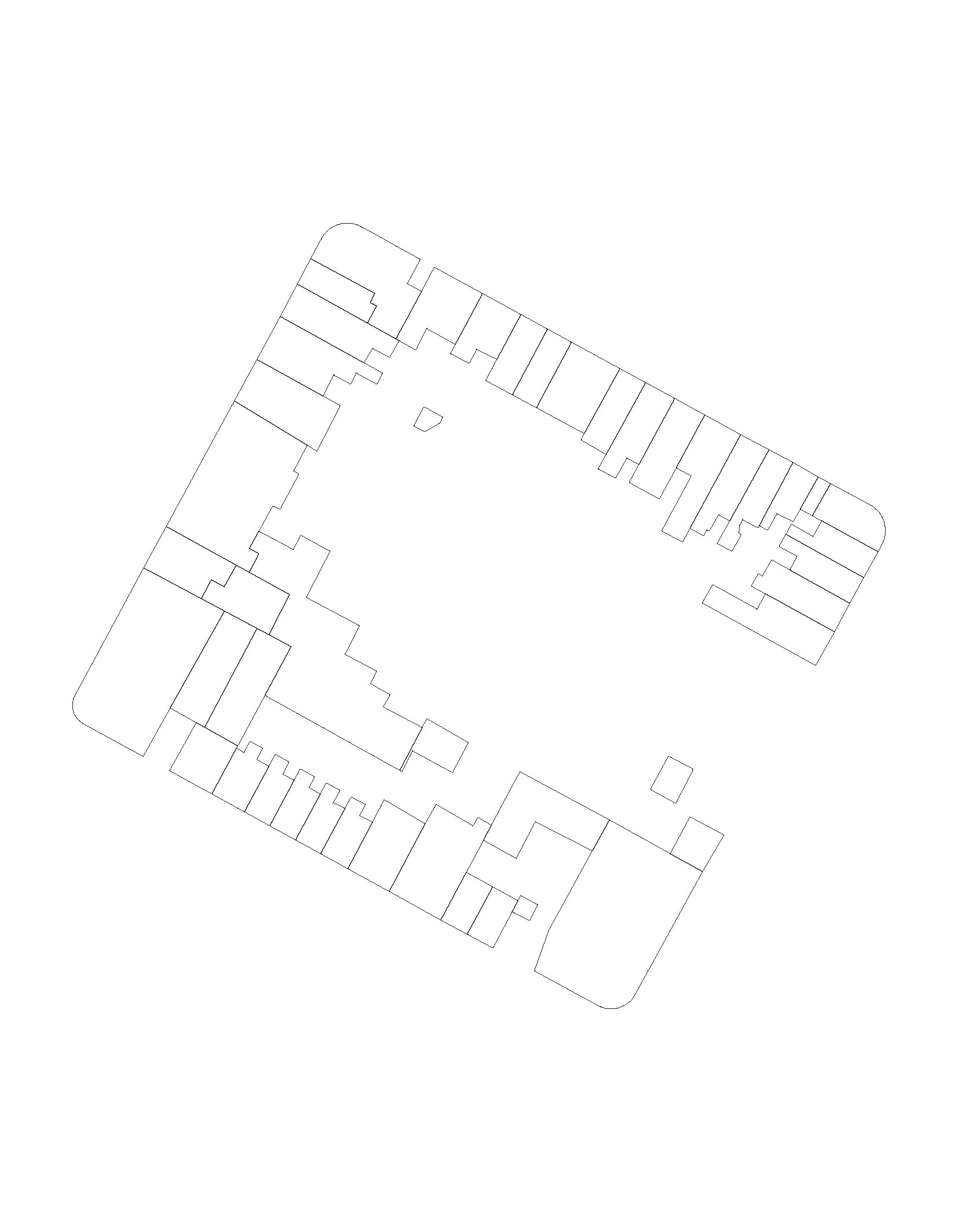

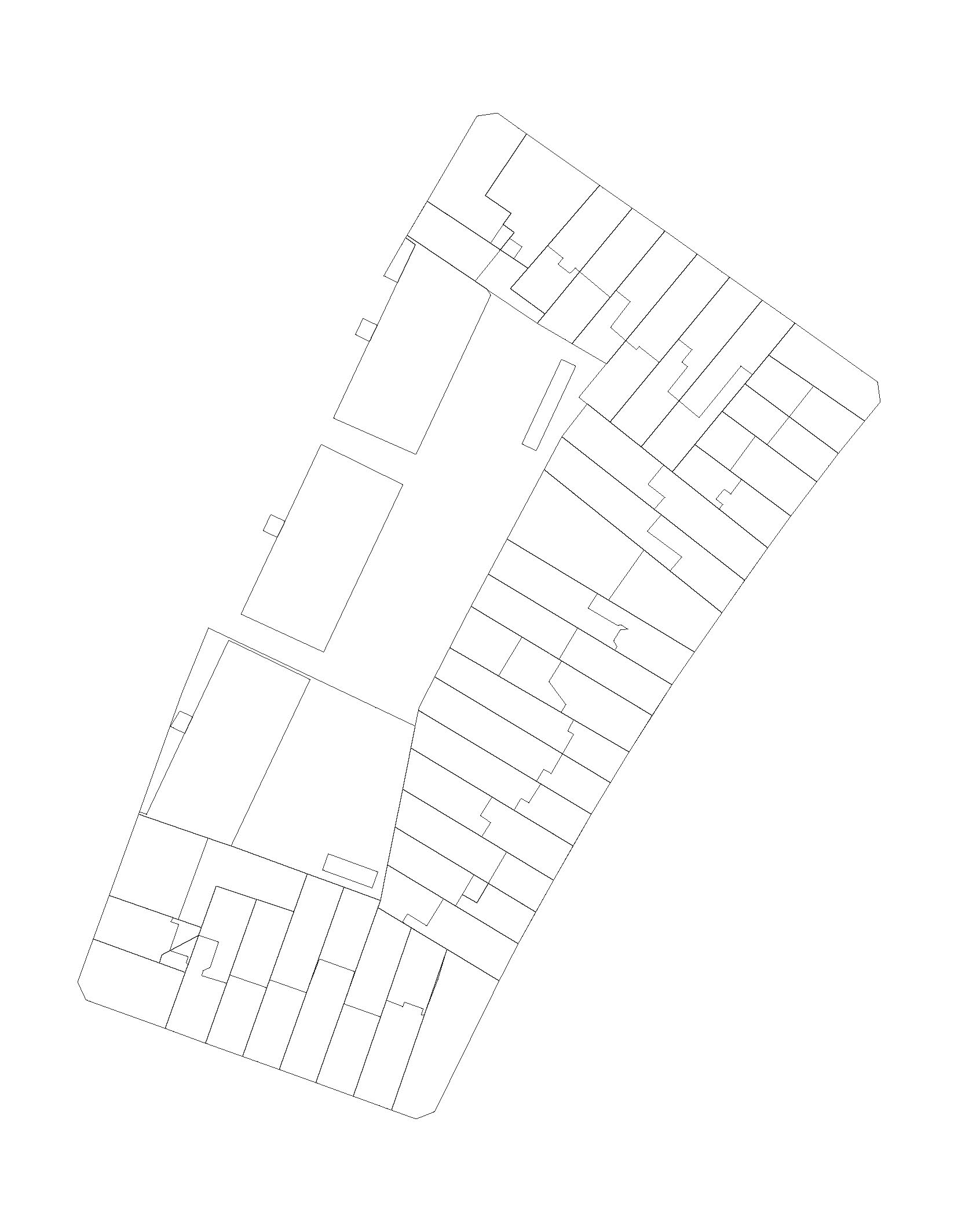

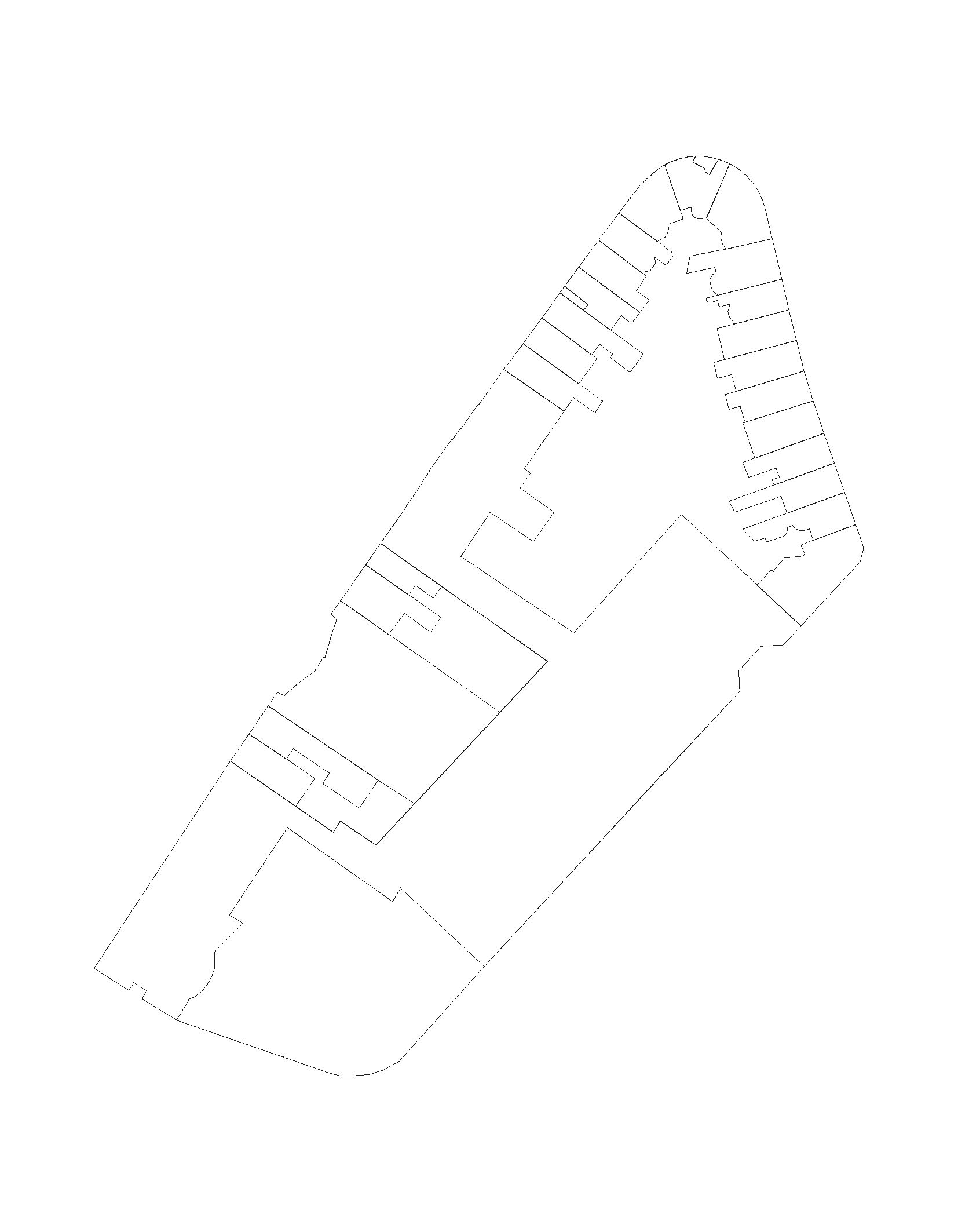

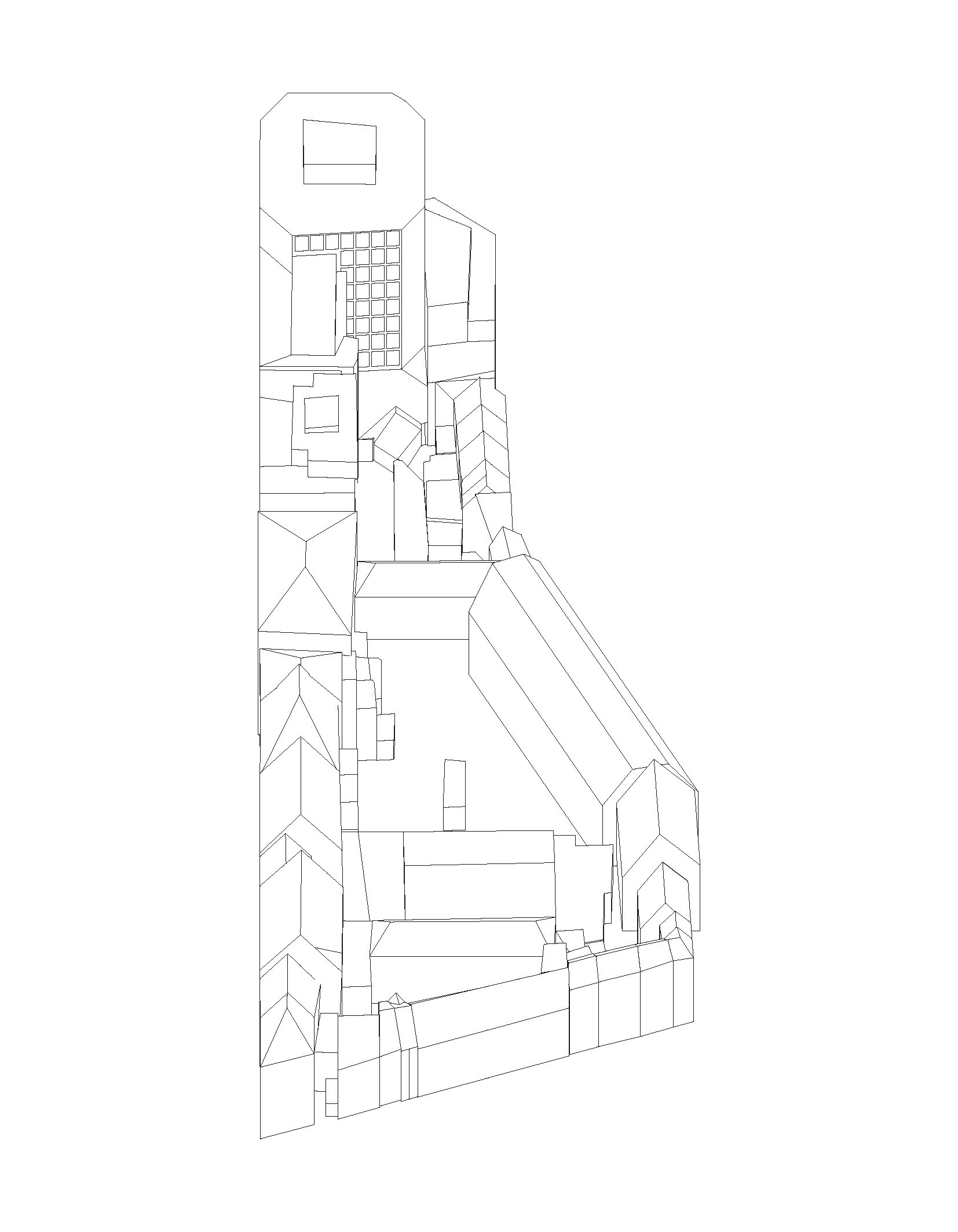

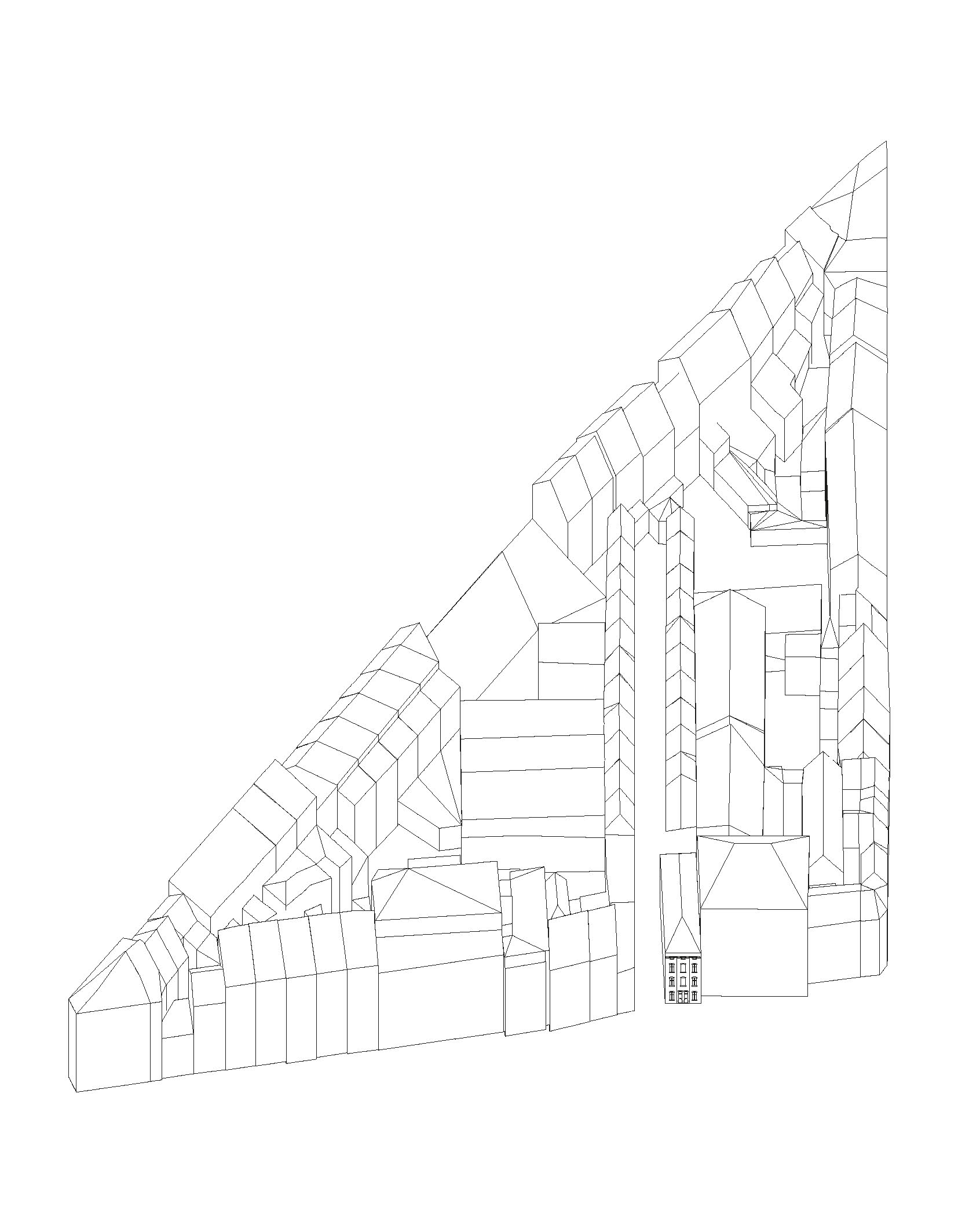

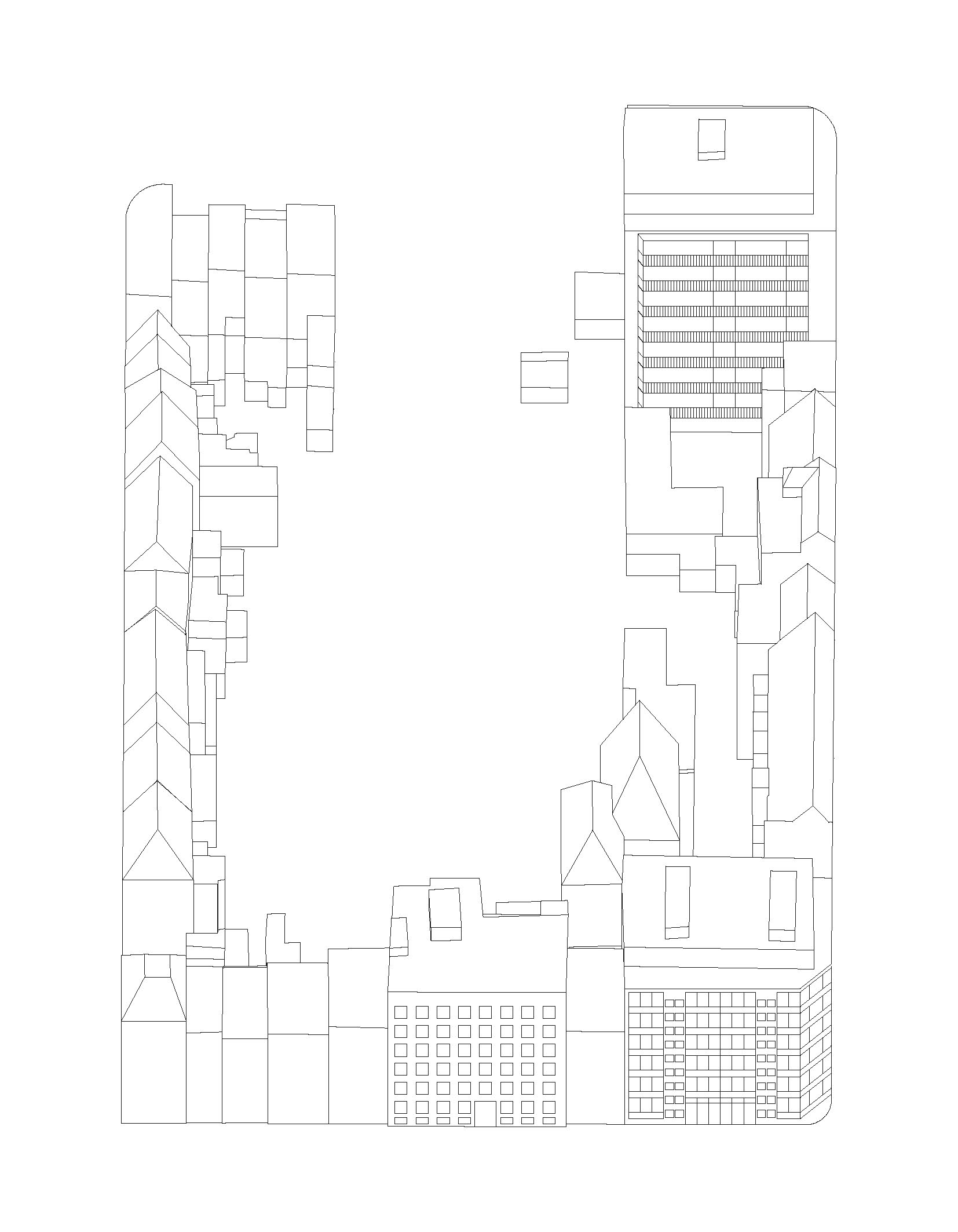

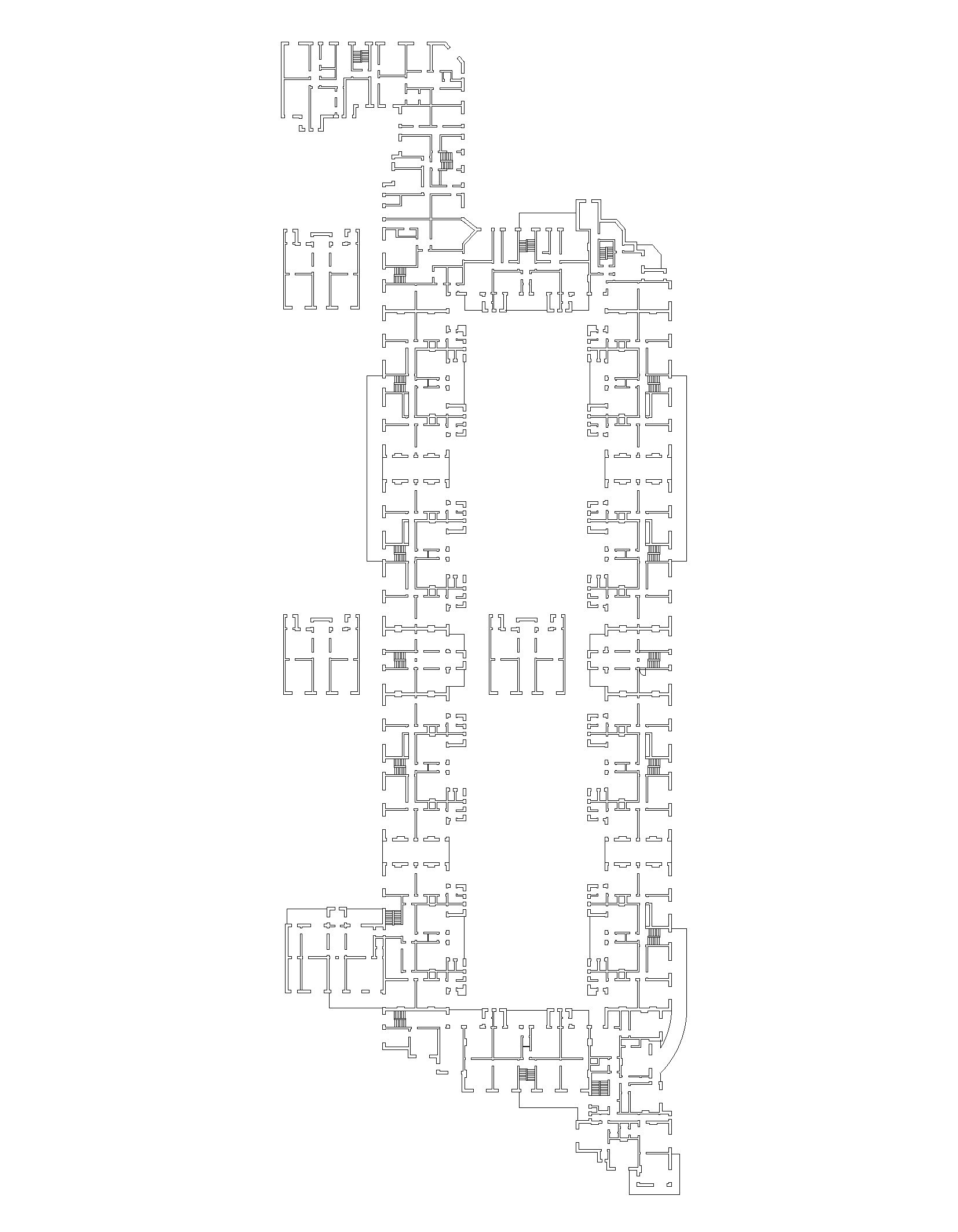

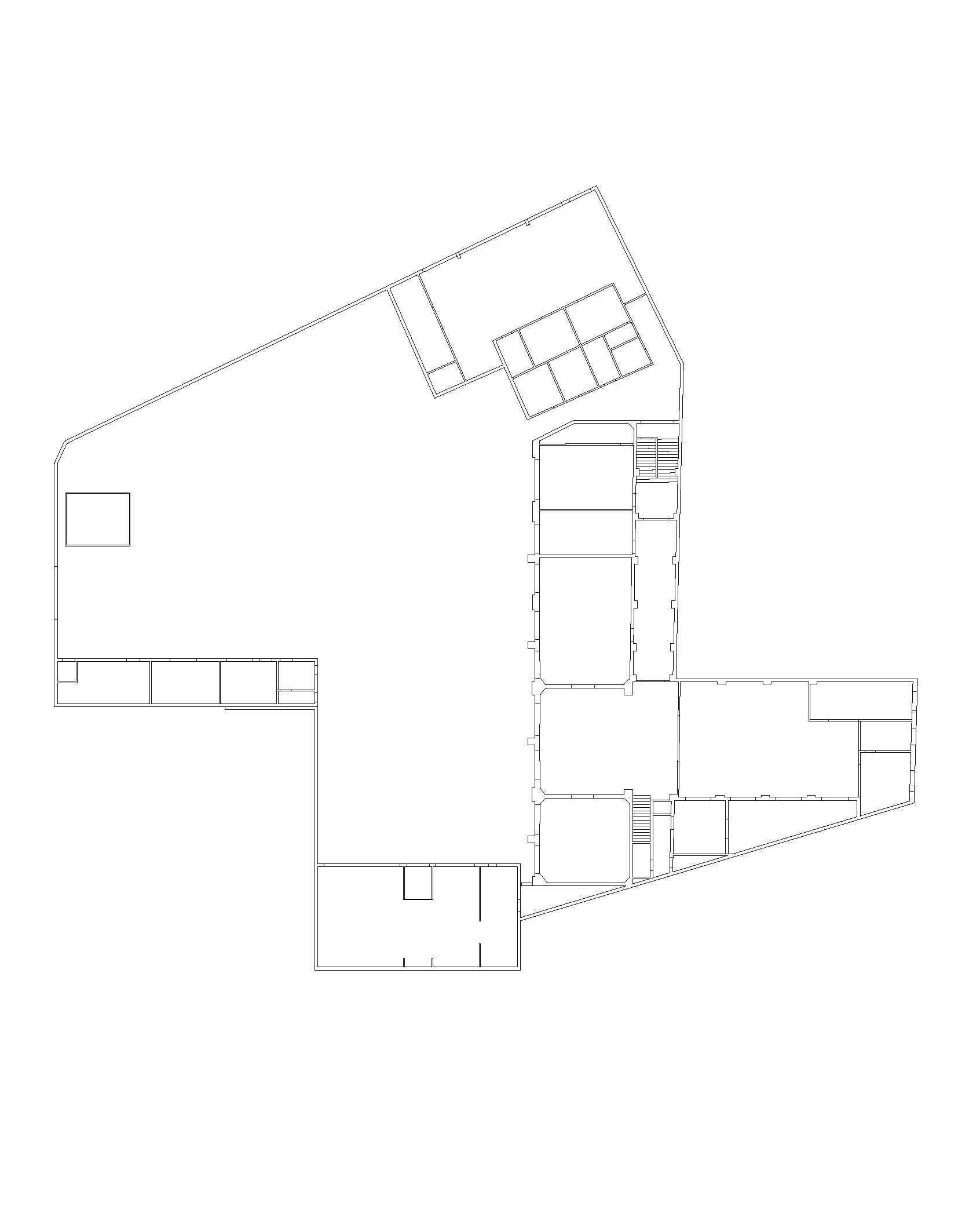

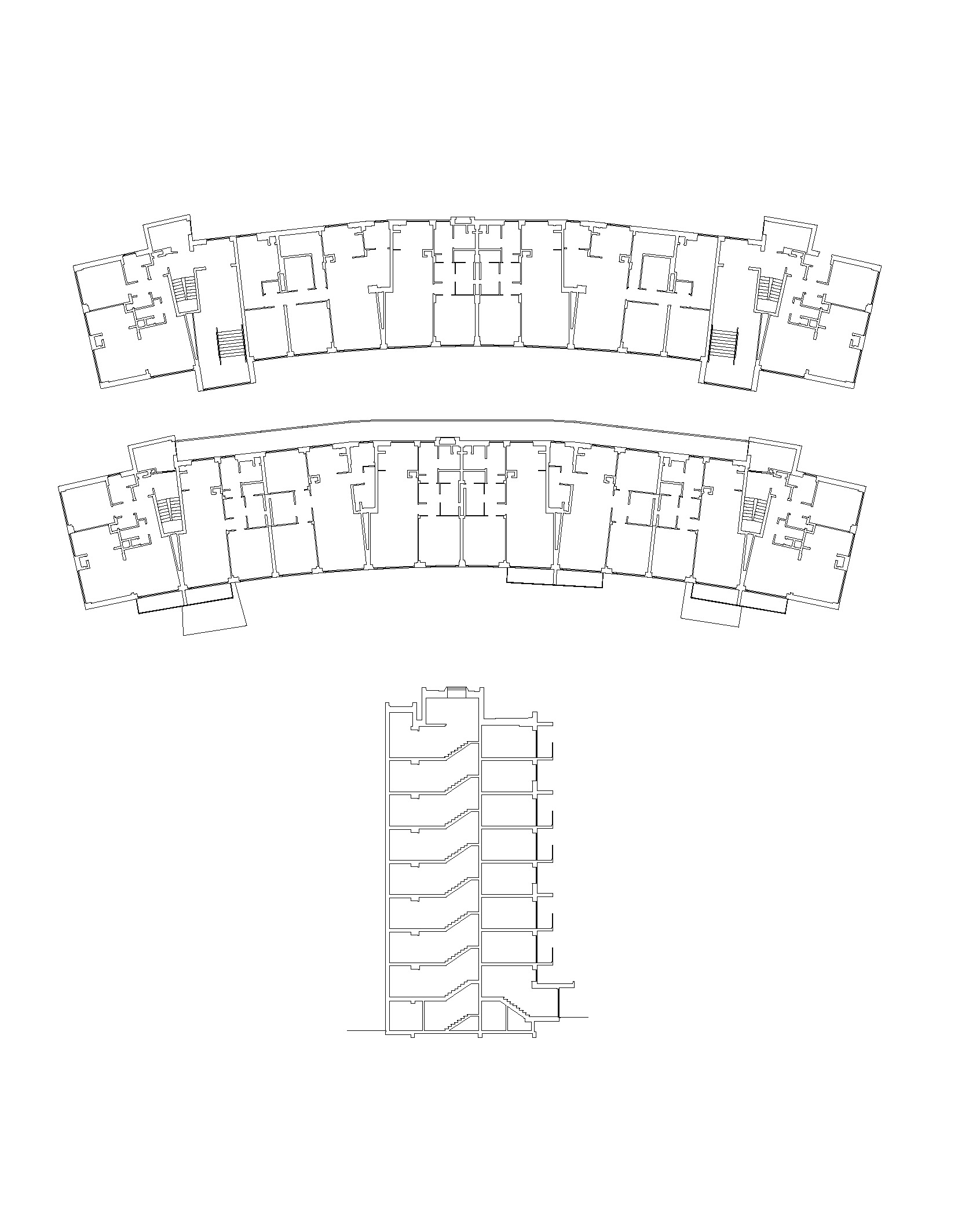

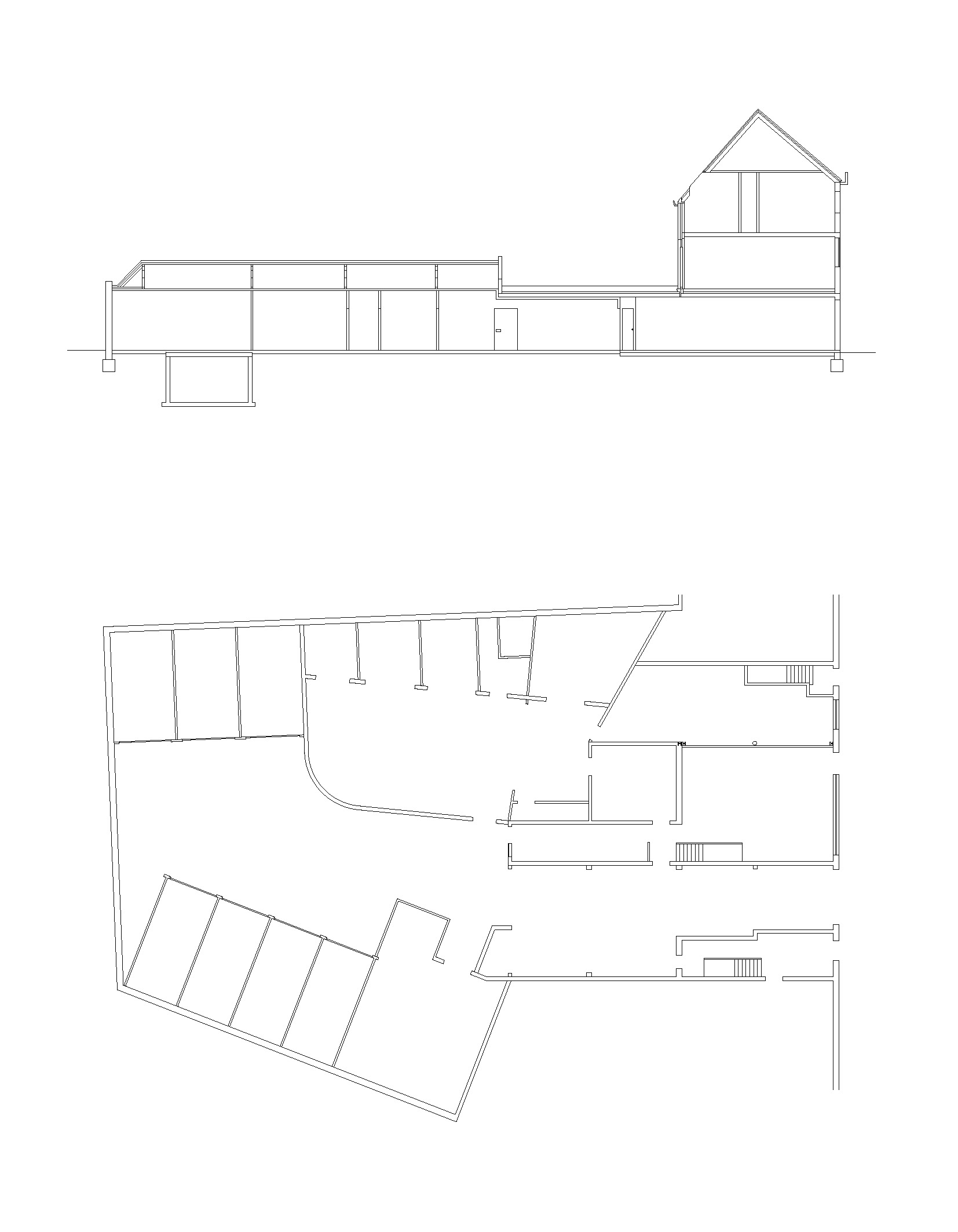

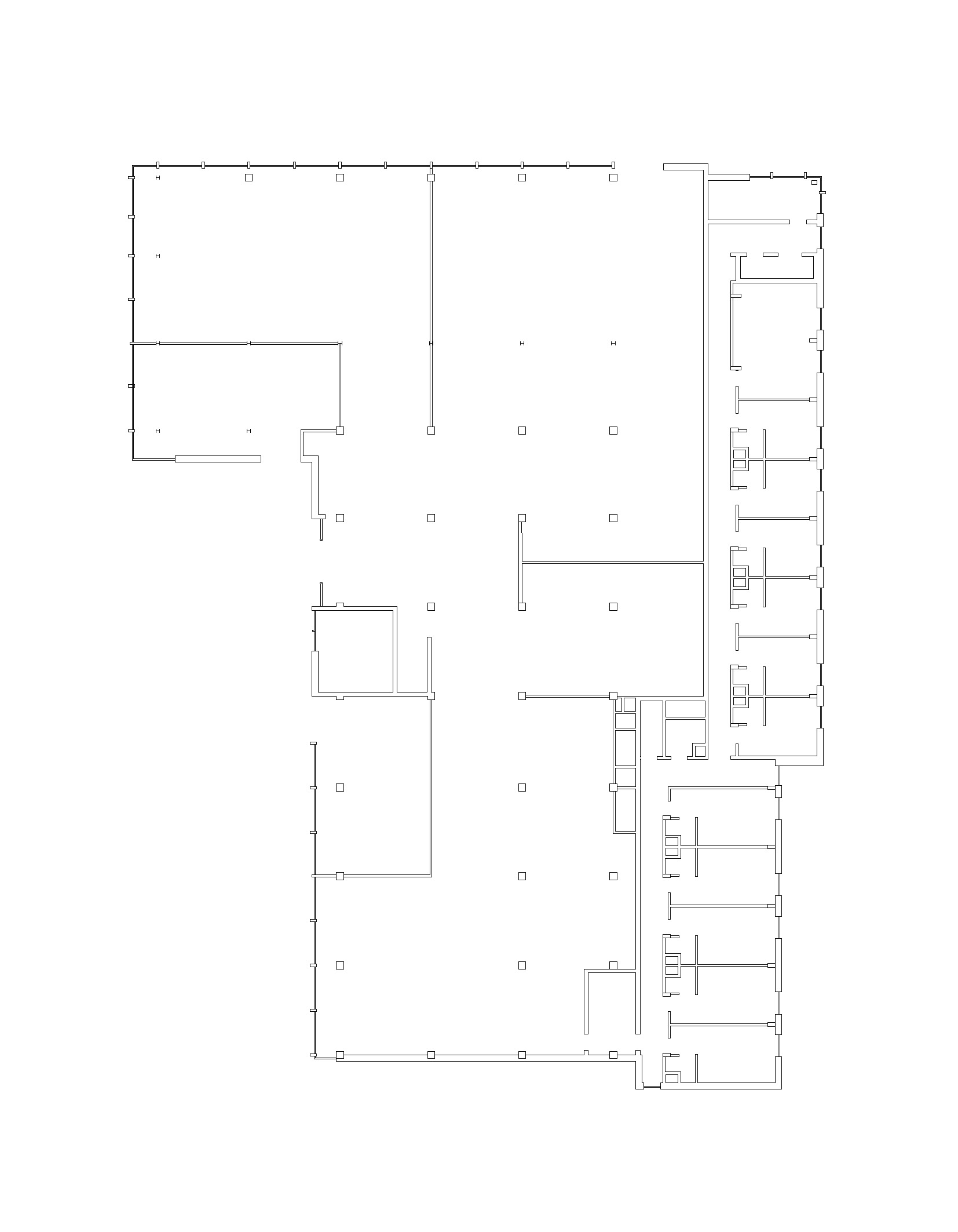

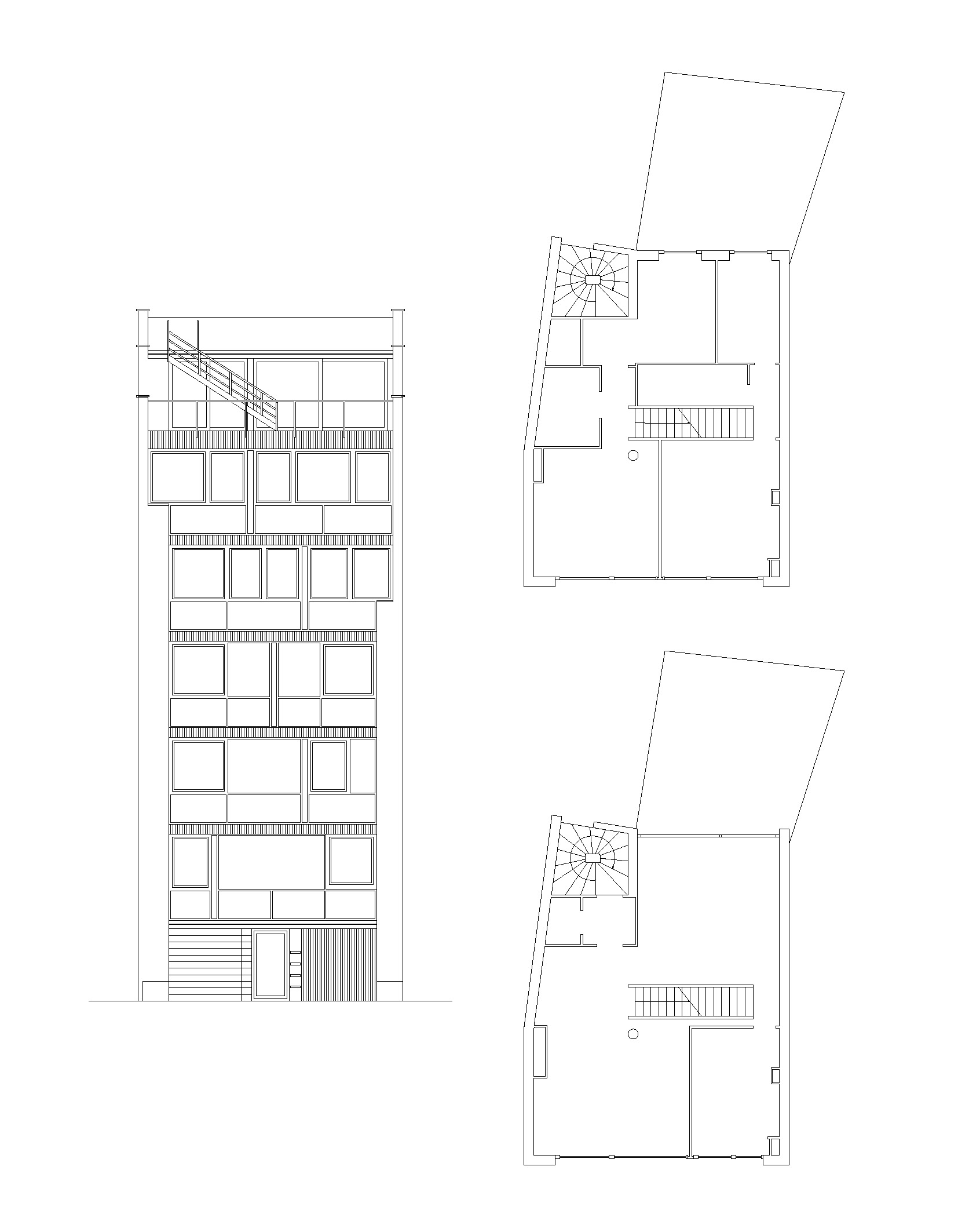

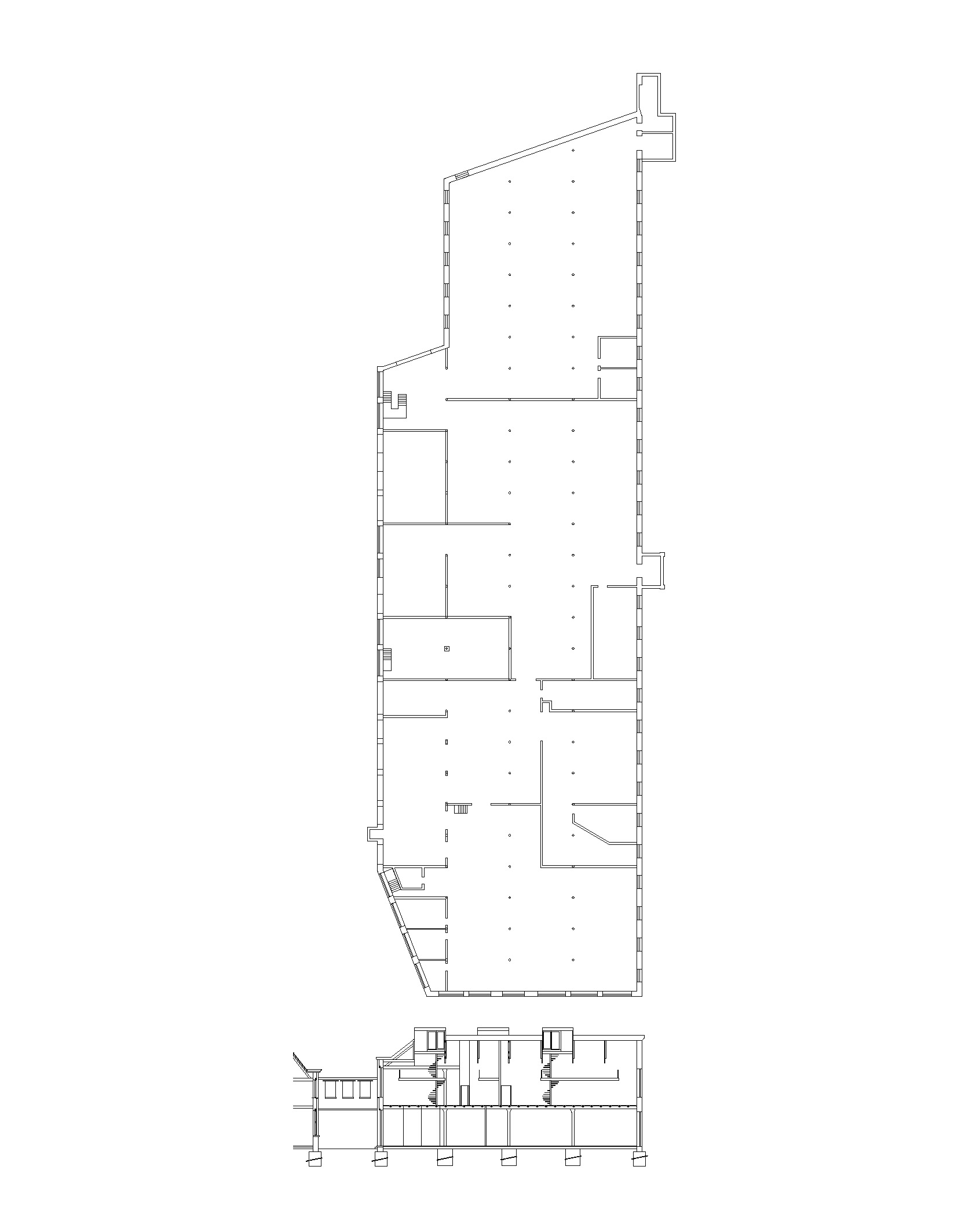

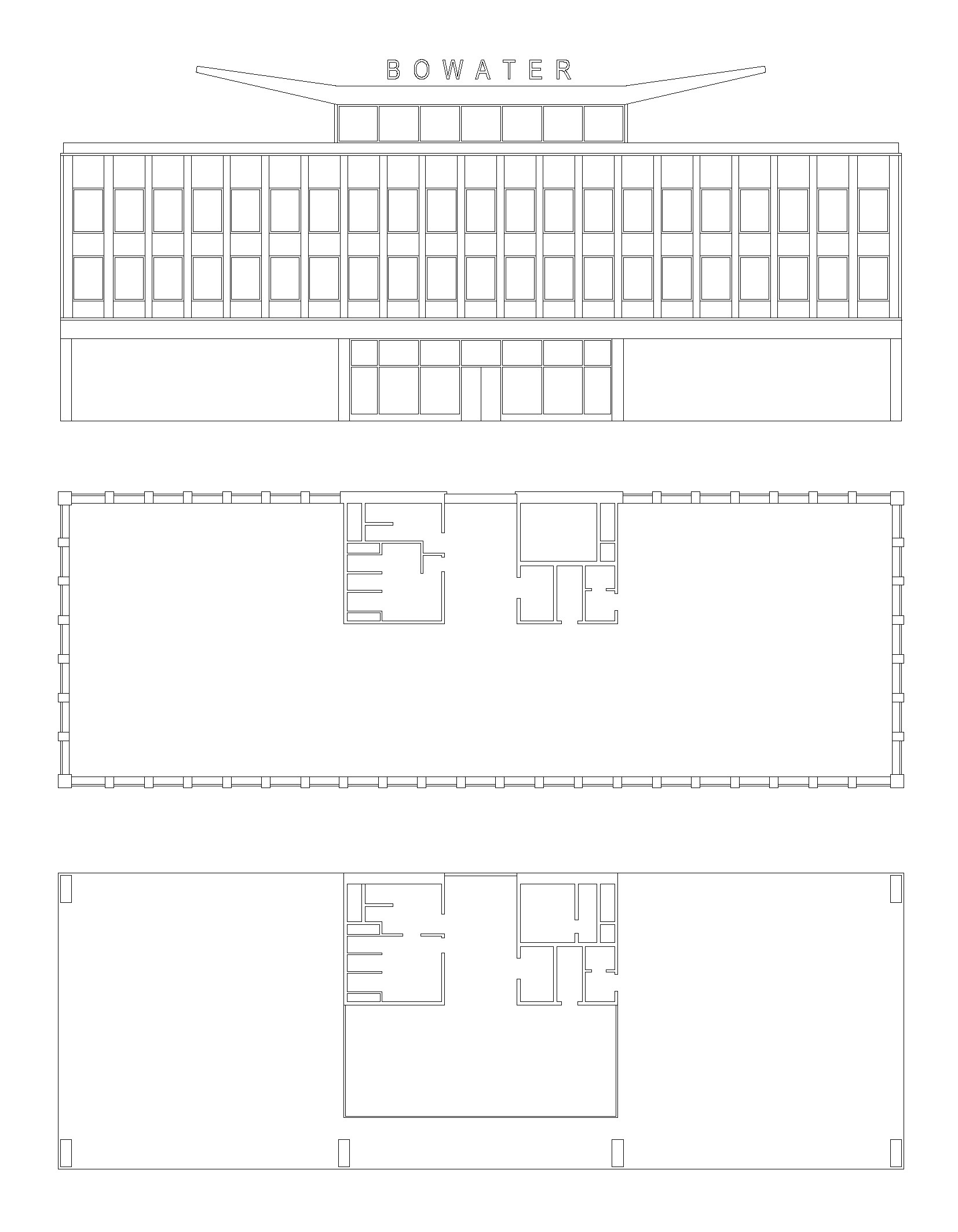

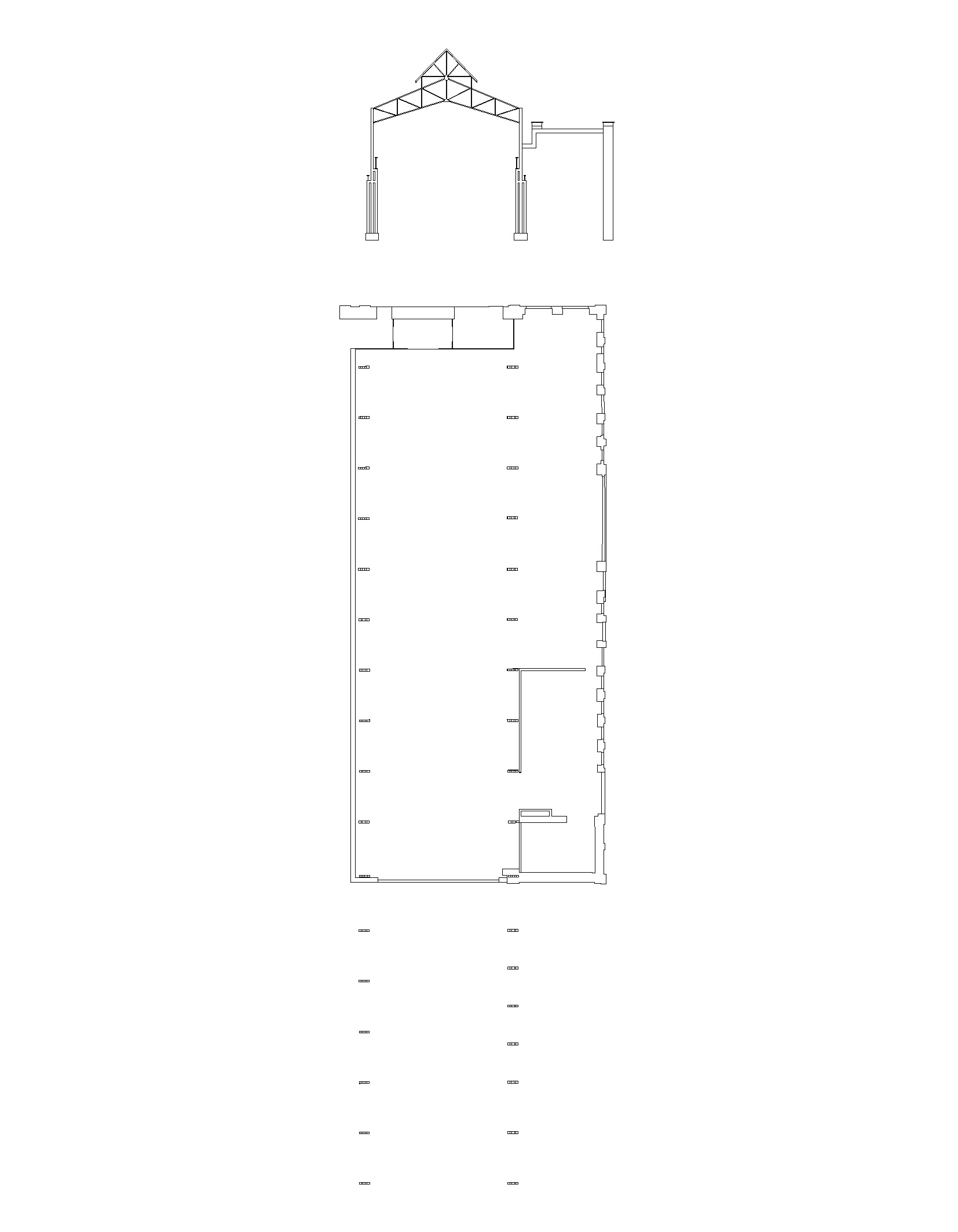

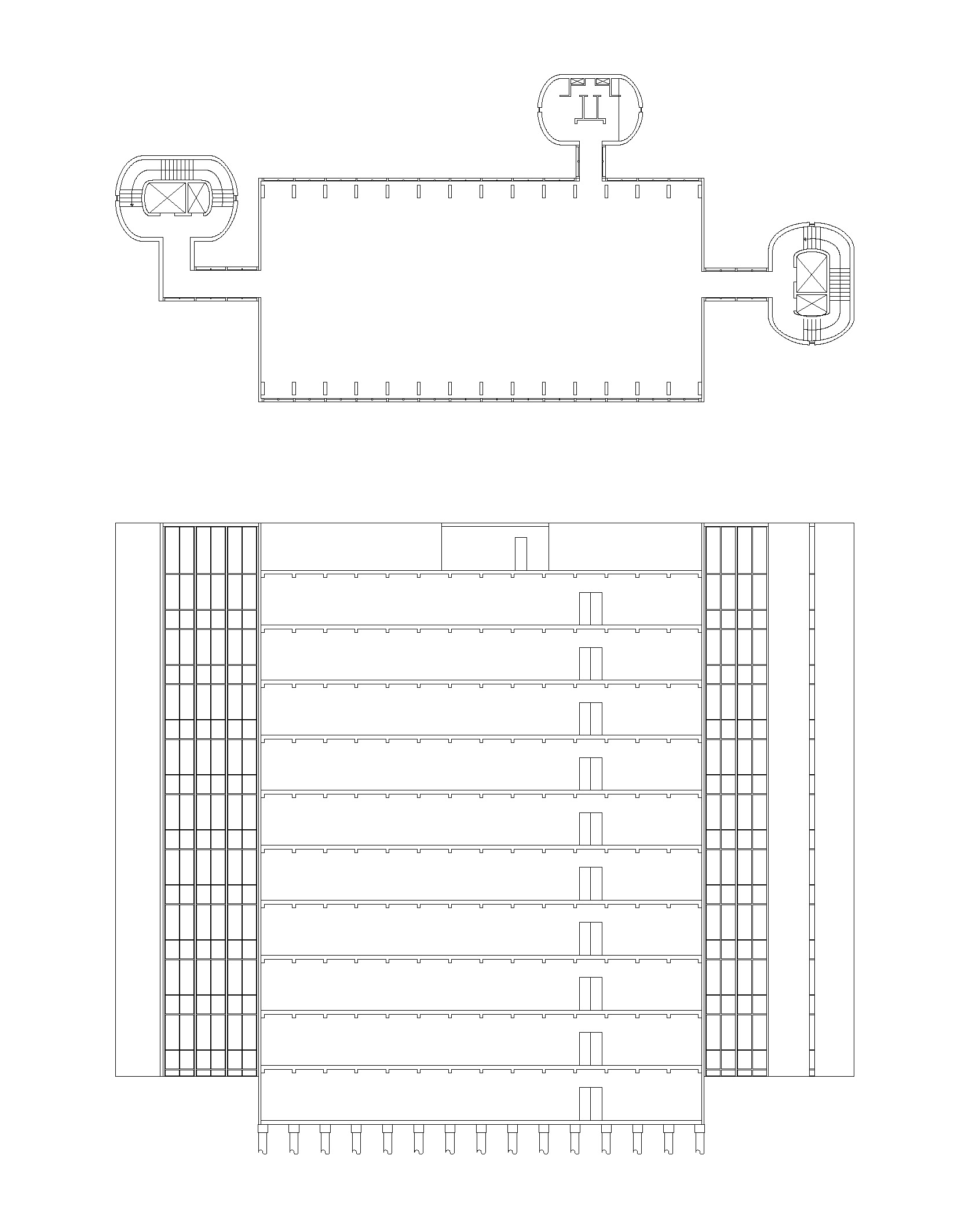

In the past studios we mainly worked on the adaptation and extension of existing structures as barns, factories and office towers. In this masterproef we will tackle the problem of the conception of a new urban building block. We will start with a crash course on the history of the building block. The group will then be divided in a historic and a contemporary research team. Historic structural examples will be compared with anonymous garages, warehouses and office blocks as found in the city of Ghent and tested for their potential as a valuable primary structure. This collection of structural types will become the building blocks from which to construct the new harbor district.

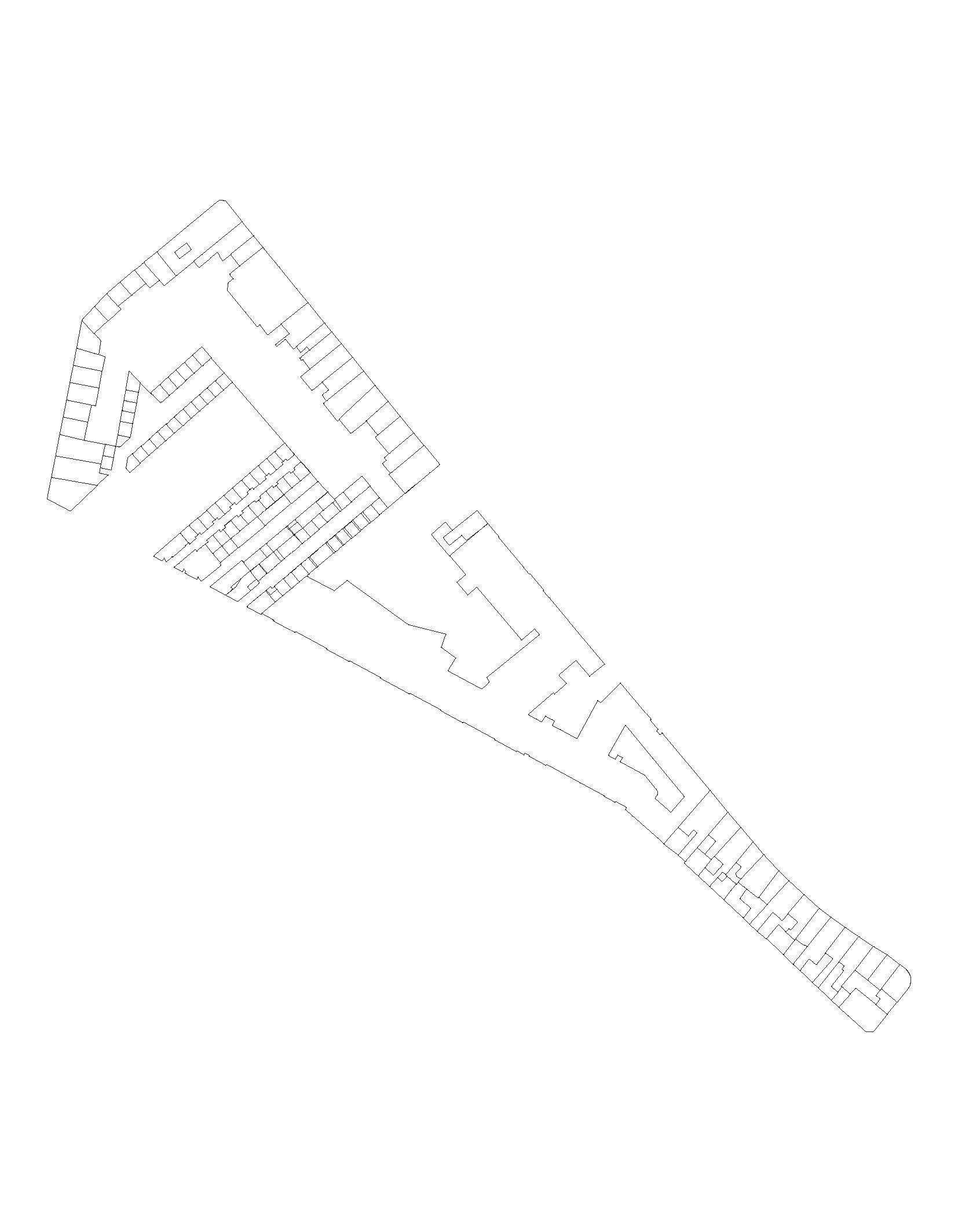

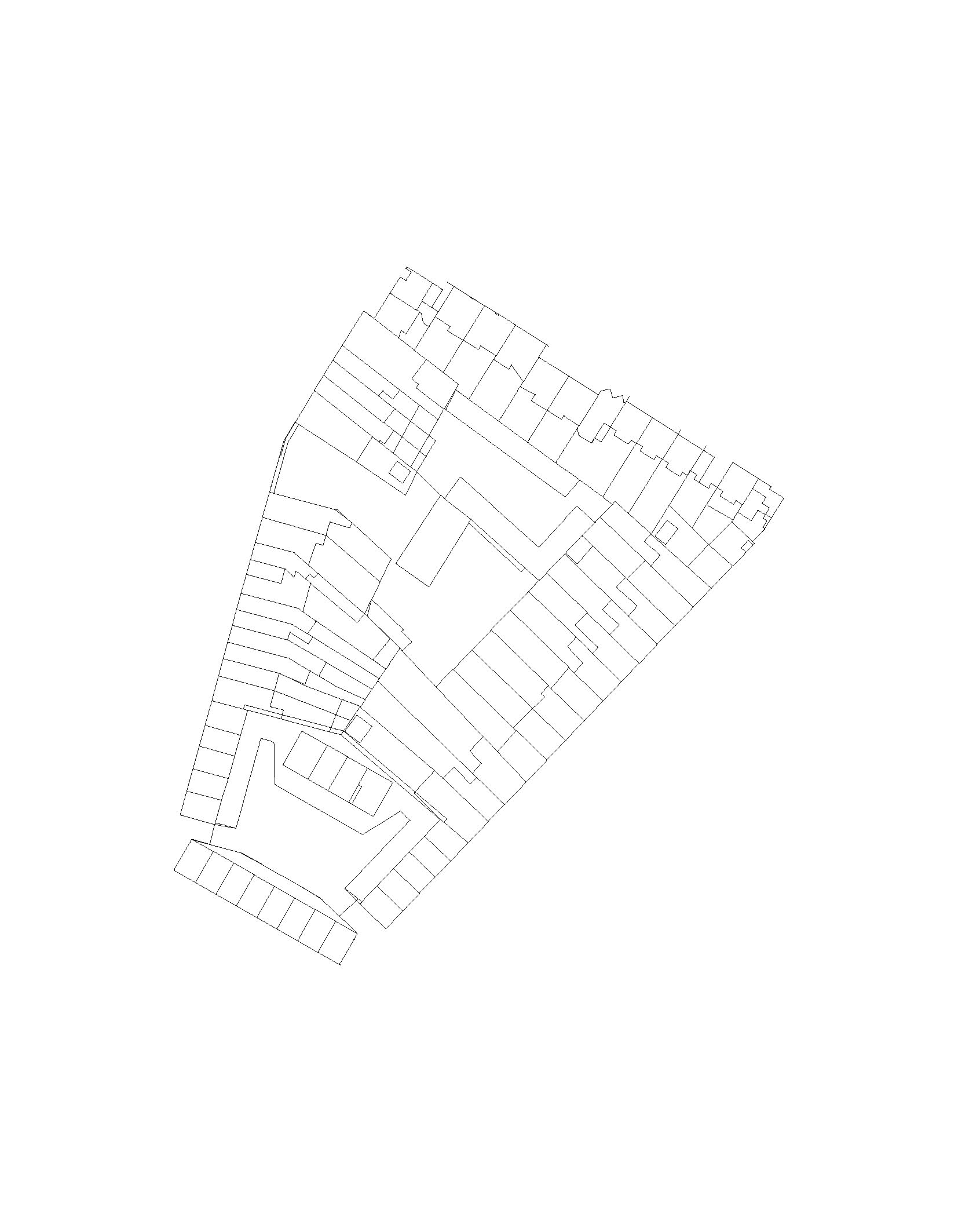

We will work within the framework of the 2006 OMA masterplan for Dok Ghent of which the first phase is recently realized. The site is located on the interface of city and harbor in between Houtdok and the Afrikalaan. The former industrial site is to be transformed into a urban landscape. The site is marked by two main factories still present and operational today. The students as a group will have to define the building block which will be tackled within the rules of the masterplan. The final design is a personal assignment but we ask for a group responsibility for the public space that will be created. As in the professional life you will have to negotiate and cooperate with your colleagues to create a meaningful whole. Every student is free to use the freshly acquired catalogue of types to cut and paste, mirror, scale combine or adapt to fit the situation and create a personal translation. Contemporary buildings strategies are tested and the material for the main structure is carefully chosen. The program is a mix of housing, offices, economic and public functions. Every student will have to make a combination of the different programs. In this assignment we do not start from scratch. We will find joy in the manipulation and the structural extrapolation of what is already there.

- READINGLIST

- About Buildings and cities podcast 84 Ian Nairn Subtopia

- Nairn, Ian. ‘Ian Nairn’s Subtopia, from June 1955’, 1 juni 1955.

- Van Zeijl, G. ‘Het gelijk van Durand’. OASE 22 (1988): 18–23.

- Durand, Jean Nicolas Louis. Précis of the Lectures on Architecture: With Graphic Portion of the Lectures on Architecture. Vertaald door David Britt. Los Angeles: The Getty Research institute, 2000.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus. A History of Building Types. Thames and Hudson, 1976.

- Lee, C.M. en Christopher. ‘The Deep Structure of Type’. In The City as a Project, onder redactie van Pierre Vittorio Aureli, 166–208. Berlin: Ruby Press, 2020.

- Colquhoun, Alan. ‘Typology and Design Method’. Perspecta 12 (1969): 71–74.